The Rebirth of the Middle Corridor

Various indications point to the re-emergence of the Middle Corridor as a potential transit route between Central Asia and Europe. While geopolitical circumstance favor the corridor, geography and poor ports infrastructure will continue to hamper the prospects.

The war in Ukraine is a devastating blow to the liberal world order. Whether Russia is defeated, victorious or stalled in a long war of attrition, the balance of power prevalent in the decades following the end of the Cold War will be changed. And a critical element of the changing geopolitical landscape will be the connectivity across the Eurasian landmass. The Russia route which for decades served as a major corridor between the EU and China is facing troubles as sanctions imposed on Moscow make Beijing fearful of potential negative economic effects on Chinese economy.

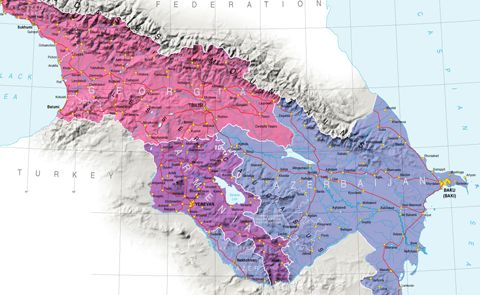

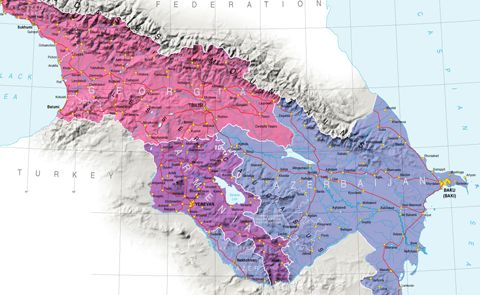

This creates favorable conditions for alternative trade corridors. And since the route via the Arctic goes along Russia’s shore and is therefore not viable in the long run because of the sanctions, China-EU trade will mainly concentrate through the Indian Ocean and the Red Sea. Yet another possibility could be the so-called Middle Corridor which runs from Turkey to Central Asia and China via the South Caucasus and the Caspian Sea. Geographically this is the shortest route between western part of China and the EU, and quite naturally the countries on the road are set to gain most from reverberations in the global networks.

Early signs of the re-emergence of the Middle Corridor are quite promising. Cargo transshipment across Central Asia and the Caucasus are expected to increase six fold to 3.2 million metric tons in 2022, compared to the previous year. In April, Maersk, a Danish shipping corporation, started a new train service along the Middle Corridor in response to changing geopolitical situation in Eurasia. Nurminen Logistics, a Finnish company, started running a container train from China to Central Europe through the trans-Caspian route on May 10. In early May a Georgian Railway team met in Ankara with counterparts from Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Kazakhstan to discuss the Middle Corridor of the Trans-Caspian International Transport Route project. On May 25, Georgia's state railway company said that it was working with businesses from Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan to develop a new shipping route employing feeder vessels between Georgia’s Poti and Romania's Constanta. This follows a joint declaration by Azerbaijan, Georgia, Kazakhstan, and Turkey in late March on improving the region's transportation potential.

There is also Turkey’s factor. The country increased its outreach to Central Asia since Azerbaijan’s victory in 2020 war with Armenia. Azerbaijan’s location has served as a launching pad for Ankara. True its potential is nevertheless constrained as Russia and China are more powerful both economically and militarily, and there is also an Iranian factor which along with Russia, loathes any non-regional presence in the Caspian region. But what is important here is that the Central Asian states which fear Russia but also in many cases feel uncomfortable to rely heavily on China, seek diversification of their foreign and economic ties. They prefer having as many foreign actors as possible to balance the two big neighbors. And this creates a favorable momentum for Turkey’s bigger penetration into the region. There has already been an upsurge in active diplomacy, including visits and pledges to enhance bilateral trade among Turkic nations.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine has served as yet another impetus. The Central Asian states and Kazakhstan in particular are seeking greater Turkish engagement because of the emerging changes in connectivity patterns across Eurasia. The Middle Corridor is now increasingly seen as a plausible alternative to Russian route. At least this is the sentiment the Kazakh president Kassym-Jomart Tokayev conveyed to his Turkish colleague during the visit to Ankara in May. The joint statement had one interesting passage on connectivity: “The Parties agreed to enhance cooperation in transport and logistics, commending the growth of cargo transit via the Baku-Tbilisi-Kars railroad and the East – West Middle Corridor. Noting fixed complex rates for the transportation of wagons and containers on Transcaspian direction of the Middle Corridor, the Parties emphasized its importance for cargo transit via new Baku-Tbilisi-Kars network. The Parties stressed the importance of strengthening coordination between the relevant institutions for the effective and sustainable use of the Middle Corridor.”

There is also a Chinese factor behind the re-invigorated Middle Corridor. For Beijing trade route alternatives are essential. As was the case with silk roads in ancient and medieval times, trade corridors rarely remain static. They adjust to emerging opportunities and evade potential geopolitical dangers. Nor is China’s massive Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) static as many have portrayed it. It evolves and adjusts to varying circumstances and though the South Caucasus has not featured high in the BRI documents published by Beijing, the region can easily fall into Chinese interests amid a new emerging geopolitical reality.

Critical infrastructure is already there. Baku-Tbilisi-Kars railway unveiled in 2017 and the improving web of region-wide roads from the Caspian to the Black Sea serve as a good starting point for China-EU trade relations through the South Caucasus. Yet geography still constitutes a major obstacle. The Middle Corridor is a multi-modal route consisting of sea and land lines. It makes the shipment more complex. There is also a glaring lack of necessary infrastructure in the Caspian Sea to guarantee easier transit from Central Asian ports to Azerbaijan. The infrastructure is also insufficient in the Black Sea where the need to have a deep sea port has now attained a bigger significance. The Anaklia saga is still continuing with no end in sight. But even if the Georgian government decides to build the port it would still take years to complete – critical period for establishing itself as a reliable transit route.

More broadly, however, China has not shown real economic interest in the South Caucasus. From the Beijing’s perspective, the region remains under Russia’s geopolitical purview and the intrusion from China might not be welcomed by the Kremlin. However, as other cases (such as in Central Asia) show, China can also go against Russian interests when and where it is critically important for Beijing. A number of indications point to the re-emergence of the Middle Corridor as a potential transit route between Central Asia and Europe, numerous obstacles such as geography and inadequate infrastructure will continue to hamper the prospects.

Emil Avdaliani is a professor at European University and the Director of Middle East Studies at Georgian think-tank, Geocase.

See Also

Economic Cooperation Between Armenia and Georgia: Potential and Challenges Ahead

Russia and Occupied Abkhazia: A New Type of Relations

Georgia and US: From Close Ties to Caution

Armenia and Georgia Strengthening Trade and Infrastructure Under Global Shifts and Sanctions