Germany, the EU, and the South Caucasus

Over the course of 2022, Germany has gradually turned from an ardent opponent of the EU expansion to its enabler. Reasons vary, but the war in Ukraine and the resulting changes in connectivity, availability of energy resources, and diminishing economic contacts with Russia push Berlin toward supporting the EU’s greater involvement in the Black Sea region and especially the South Caucasus.

The Zeitenwende speech made by German Chancellor Olaf Scholz on February 27, several days following the beginning of Russia’s disastrous war on Ukraine, seemed to usher in a new era for Germany’s foreign policy and its perception of security threats in eastern Europe.

The speech, as it turned out in the months that followed, was the start of a comprehensive process that laid out the programme for changing Germany's decades-long foreign policy principles. While all attention was paid to Scholz’s transformative measures in defense spending and Germany’s attitude toward Russia, a likewise critical change took place in Germany’s approach to the enlargement of the European Union.

Before Russia’s second invasion of Ukraine, Europe was different, and Germany was seen as one of the abettors of Russian influence on the continent. Reliance on Russian gas was falsely seen not as a geopolitical danger but rather as a sign of mutual dependence. Berlin was likewise highly sceptical about the EU’s enlargement plans as well as NATO’s expansion eastward. For instance, in 2008, Germany’s position was critical in blocking the granting of the NATO membership action plan (MAP) to Georgia and Ukraine. Similarly, the inclusion of Ukraine and Georgia into the EU was also seen at best as an impractical political move. Both scenarios were regarded by the German political elite as dangerous moves which that would damage relations with Russia and radicalize the latter’s foreign policy.

Instead, abstention from expansion eastward was seen as a recipe for stable ties with Moscow. The latter was seen as a highly pragmatic actor which would tolerate NATO and EU existence but will understandably become wary of these two Western entities’ expansion along Russian borders. This status quo seemed to work. German business elites expanded commercial ties with Russia, while the latter viewed Berlin as a cornerstone of its relations with the EU. The annexation of Crimea in 2014 as well as the invasion of Georgia in 2008 were seen as aberrations in Russian behavior and rarely featured in Germany’s political debates.

This political approach, however, was fraught with dangers and practical mistakes. It demonstrated that the German political elite did not quite understand Moscow’s true intentions. For the Kremlin, close ties with Germany were seen as a necessary tool to sow divisions within the trans-Atlantic community. Moreover, few, if any, suspected that Moscow was intent on rebuilding a true territorial empire. For decades, numerous analysts’ and some scholars’ claims that Russia was willing to build a new Soviet Union were derided both in Germany and in much of the EU. Yet, Russia did not only dream about aggrandizement of its exclusive sphere of influence, but actually reconstituting the old Russian Empire – a much more dangerous development than the pursuit of the Soviet model. In the new Russian Empire envisioned by the Russian leadership, large territories of Ukraine and other neighboring countries would one day become part of Russia proper.

The mistakes by the German political elites became apparent in February 2022, when Russia launched a full-scale attack on Ukraine with the goal of changing the European security architecture by building an exclusive sphere of geopolitical influence over neighboring states. The invasion caused a major re-think in Germany, not only in regard to Russia but generally toward the future of the EU, NATO, and the trans-Atlantic community.

First, the German leadership realized the need to expand the EU. The chancellor Scholz memorably said in one of his public statements that “We are the people of Europe, and our voice must be heard throughout Europe, from the Mediterranean to the North Sea, from Lisbon to Tbilisi and beyond”.

In a highly-discussed op-ed for the Foreign Affairs Scholz wrote that “Putin wanted to divide Europe into zones of influence and to divide the world into blocs of great powers and vassal states. Instead, his war has served only to advance the EU. At the European Council in June 2022, the EU granted Ukraine and Moldova the status of “candidate countries” and reaffirmed that Georgia’s future lies with Europe. We also agreed that the EU accession of all six countries of the western Balkans must finally become a reality, a goal to which I am personally committed. That is why I have revived the so-called Berlin Process for the western Balkans, which intends to deepen cooperation in the region, bringing its countries and their citizens closer together and preparing them for EU integration”.

In another passage from the same article, he argued that “It is important to acknowledge that expanding the EU and integrating new members will be difficult; nothing would be worse than giving millions of people false hope. But the way is open, and the goal is clear: an EU that will consist of over 500 million free citizens”.

Those are not mere statements. They reflect a growing realization in Germany as well as elsewhere in Europe that the best guarantee against future Russian attacks on its neighbors is the expansion of the European institutions (potentially backed up by NATO). But behind these benign designs lurk changing geopolitical circumstances. Germany needs EU expansion because the EU is now increasingly seeking new gas and oil resources. Germany and the EU as a whole are also looking for alternatives to the north Eurasian transport route, which largely passed through Russia and linked Europe to Central Asia and, most importantly, China.

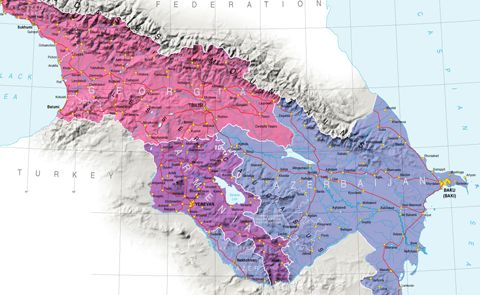

In both cases, the eastern Black Sea and the South Caucasus play a critical role. The route through Georgia would safeguard alternative energy resources from the Caspian Sea as well as the expansion of the transport route, nowadays fashionably called the Middle Corridor. The recent signing of the agreement for the development of the 1,100-kilometer-long Black Sea strategic submarine electricity cable is yet another sign of how geopolitical has become the EU’s approach to the Black Sea region and the South Caucasus.

The long-term perspective is thus favorable for Georgia and the wider Black Sea region. The EU, powered by a changing perspective in Berlin, is now pushing for greater involvement in the region. Here are no guarantees, but considering the existing geopolitical (the prolonged war in Ukraine) and geo-economic (Europe’s energy decoupling from Russia) trends, it is obvious that Germany is likely to deepen its commitment to the EU and perhaps even NATO’s expansion eastward. Amid the granting of European perspective granted to Georgia in July 2022 it is also fair to say that Tbilisi has now good chances to obtain European candidate status.

Emil Avdaliani is a professor at European University and the Director of Middle East Studies at the Georgian think-tank, Geocase.

See Also

From Neorealism to Neoliberalism: Armenia’s Strategic Pivot in Foreign Policy After the Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict

Georgia and Russia: New Turn in Bilateral Relations

3+3 Initiative as a New Order in the South Caucasus

Economic Cooperation Between Armenia and Georgia: Potential and Challenges Ahead