Organized Crime as an Obstacle to Georgia's EU Integration

About the author: Nick Baigent is a New Zealander who lives and works in Tbilisi, Georgia. He has a Masters from the University of Glasgow in Russian, Central and East European Studies and now is involved working on the Transcaucasian Trail Project as well as freelancing across the country. He has spent time living and working in the Ukraine, Poland, and Georgia and has a particular interest in South Caucasus politics.

Introduction

In April this year it was reported that 20 members of the “Georgian Mafia” had been arrested in Spain. This marked the latest in a long line of similar arrests since the mid-2000s. Organized crime is a central concern in Georgia-EU accession discussions - the French Interior Minister Christophe Castaner flew in after the recent arrests to discuss the issue specifically with high ranking Georgian officials. Over recent years there has been a disproportionate number of Georgians seeking asylum in EU member states for a country as stable as Georgia. Coinciding with this has been an increased presence of the Thieves-in-Law in EU member states. When the “the Georgian Mafia” is described, it is to the Thieves-in-Law which people are (usually) referring. The mistake is not a crucial one, however, the Thieves-in-Law is not a cohesive top down organized unit, it is a collection of criminal entities that ascribe to the same codes and honour systems - the code of thieves. What is important is the perception which is created by the actions, reporting, and politicization of the Georgian-Thieves-in-law across the EU.

Georgia has displayed near unwavering commitment to joining the European Union since the 2004 Rose Revolution. This commitment has been maintained across multiple governments and constitutional amendments - an impressive feat given the apocalyptic rhetoric surrounding opposition politics in this country. Progress has been made towards achieving this goal, but it has been slow, with many arguing that the efforts made by Georgia will be futile in ultimately achieving full membership. The core reason presented for this is geopolitical. There is concern over potential Russian retaliation if Georgia gains membership to the EU or NATO (a similar argument is made on the subject of Ukrainian accession). Furthermore, the Union’s own splintered views on expansion also provides a significant obstacle to inclusion. However, beyond this there are a myriad of issues on the periphery which provide bureaucratic legitimacy to the glacial pace of the process. The legacies of organized crime in Georgia is one such example.

Organized crime is certainly a legitimate issue and the anomalously high level of asylum seekers from Georgia to the EU is indeed serious. However, it is important to note that a core reason for the reason of a Georgian organized crime presence in the EU is due to the success of anti-mafia reforms which have been adopted within Georgia.

Georgia in the 1990s

In the 1990s Georgian politics and civil society was dominated by organized crime. As was the case across the former USSR, the years immediately following the disintegration of Communism ushered in a harsh decade. Challenges were widespread but were particularly potent in the South Caucasus as conflicts emerged, lingered, and then froze across the region. Abkhazia, South Ossetia, and Nagorno Karabakh were all sites of deadly and prolonged conflict.

The government in Tbilisi did not have administrative control of the country at this time. Numerous prominent Thieves-in-Law seized upon this opportunity blurring the lines between government and organized crime. Jaba Ioseliani is famously rumoured to have been responsible for bringing Eduard Shevardnadze back to the country to become President and oust the vehemently nationalistic Zviad Gamsakhurdia, with whom Ioseliani’s Mkhedrioni forces had been fighting during the civil war of the early 1990s. However, beyond this, the ineffective government and lack of civil society resulted in the Thieves-in-Law ingraining themselves in everyday life - in many instances they were the presence that the government was not (Slade, 2013). This role was facilitated in part due to the structure that defines the Thieves-in-Law.

The Thieves-in-Law are frequently referred to as a mafia or organized crime group. However, this in itself is problematic as this paints the picture of a top down structure. This is inaccurate. One expert on the Thieves-in-Law defines them as “an exclusive network of elite status criminals that shared rituals and norms”. Given the EU has focused on organized crime within Georgia as a problem and this focus refers to actions linked with Thief-in-Law activity this article also adopts the word “organization” when referring to the Thieves-in-Law for simplicity. However, it is a flawed way of understanding Georgian crime abroad, as this article tries to establish.

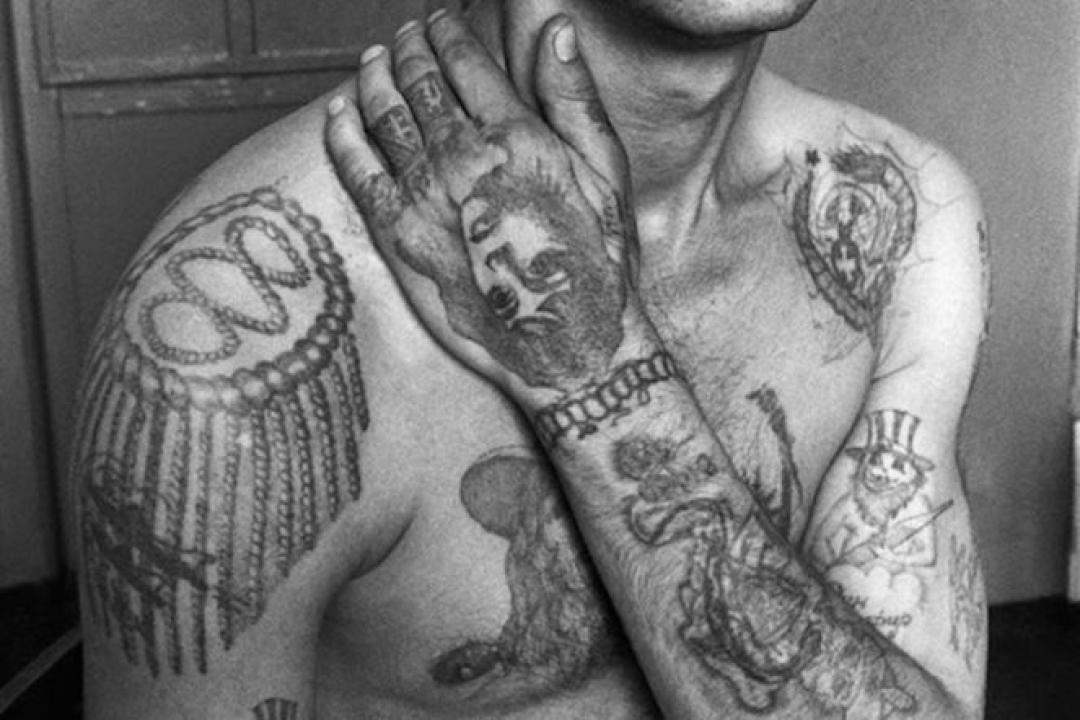

The honour code which governs the Thieves-in-Law was born out of Stalin’s soviet Gulags. These communal prisons fostered a social order that permeated across prison walls, and then into the criminal underground of what are now post-Soviet countries. There are many elements to this order, but it is the use of tattoos that are most commonly associated with it. Tattoos served as a means to communicate an individual's status within this social structure so that if a prisoner was moved their position and their previous actions would be recognized by their new inmates. Naturally, this moved beyond jails as prisoners were released. Thus, a ready made criminal underworld emerged from the Gulags for the countries within the USSR.

Soviet Prisons nonetheless were the place in which the worldview that would define thievery for so many across the Soviet space was born. Indeed, describing the Thieves-in-Law as a criminal organization is flawed. Thieves-in-Law are the select few that have risen to the top of the thieves world, - qurduli samkaro in Georgian and vorovskoi mir in Russian. Upon obtaining the title of Thief-in-Law a person is theoretically of equal rank with all others holding that title. Underneath them is the thieves world and all those who operate within it. Originally this had been defined by prison structures, but as thieves were released roles and parameters would become blurred. However, for the sake of structure and clarity in this article, the hierarchy born out of the prison systems is listed below:

-

Avtoriteti/authorities (full thief in law)

-

Shesterki/sixers (overseers) - these people would be directly charged as a Thief-in-Law’s representative.

-

Kai bichebi/goodfellas (those that refused to work) - these were prisoners who refused to work in the prisons and did not fraternize with prison workers. They supported the Thieves-in-Law and were a part of the thieves’ world.

Then there was a line of delineation between those within the world and those outside of it.

-

Muzhiki/peasants (those that work) - these were people who worked and cooperated with prison officers.

-

Kozli/goats (snitches) - the kozli were people who embedded themselves with the prison regime, they are whistleblowers and colluders.

-

opushennie (the lowest of the low) - these were homosexuals and pedophiles, they had no standing within the criminal system.

Georgians proved to be particularly adept at rising through these ranks. Finding consistent statistics on the number of Georgians within the Thieves-in-Law ranks is difficult, but studies in the early 2000s established that Georgians made up at least 30% (Glonti & Lobjanidze 2004) of the total number of active Thieves-in-Law, with some Russian newspapers claiming they made up to 65% (Kalinin 2001). The accuracy of the statistics is ultimately a moot point, what is important to comprehend is just how prevalent Georgians were within this power system.

This prevalence combined with the chaos of the 1990s allowed Georgian Thieves-in-Law to accumulate huge amounts of power over the decade. Not only did they have the resources (money and muscle) but due to the weak structure of Georgia’s political system at the time they were able to undergo a process of what Stefes (2006) labels as state capture. Gavin Slade (2012) summarizes one particularly potent example of this:

“In this period then there was toleration and facilitation of the professional criminal actors who ran criminal enterprises and mafia groups by key state actors based on apparent commitment to each other. Integration between the state and the Thieves-in-Law was clearly on display as late as 2003 when the Georgian Government’s plenipotentiary in the Kodori Gorge utilised its connections with the Thieves-in-Law to rescue UN workers being held hostage, these connections were unashamedly reported by government representatives.”

If this was still the case it would bode poorly for Georgia’s hopes of joining the EU. However, after the Rose Revolution Georgia would adopt harsh but successful anti-organized crime measures.

Reforms from 2004

Central to Mikheil Saakashvilli’s rise to power was his promise to eliminate corruption. Despite Saashvilli’s later failings and hubris, tackling police corruption and organized crime were some of his greatest accomplishments. All traffic police were fired overnight and required to apply for their jobs once more. The prison system - the essential recruiting ground for Thieves-in-Law - was completely revamped and the barracks style system (and open system was replaced by a cell system) which had given rise to the thieves structure was eliminated, and it was made illegal for someone to identify as a Thief-in-Law (to deny one’s status went against the code of honour which dictated a thieves way of life) (Slade, 2012). This policy was potent in its effectiveness, it led to the quick arrest of around 40 Thieves-in-Law while many others fled the country after just a few months. Furthermore, special prisons were constructed for the thieves that separated them from the rest of the prison populace, over whom they would have dominance.

The success of these policies cannot be understated. Organized crime has gone from being a mainstay of politics and everyday life, to a rare underground phenomenon (Caucasus Barometer, 2017). The fact that this transformation has taken place is essential for understanding the Georgian crime that is happening in the EU.

Legacy

Academia is obsessed with the idea of post-soviet legacies. The Thieves-in-Law in Georgia offer one of the more tangible representations of what this really means. Despite largely successfully addressing this issue internally, shedding the lingering ripples of the years of ingrained crime is difficult. In 2016, according to German police data, there were nearly 6,500 Georgians registered as criminal suspects within the police forces database. This is only a small fraction of registered criminal suspects in total, however, it is the second highest originating from Eastern Europe (Russia is the highest, a country much larger than Georgia) (Eurasianet, 2018).

This, combined with the high rate of Georgian asylum seekers, is what concerns EU officials. Indeed, it was used as reason to delay the implementation of the EU-waiver programme in the first place. Furthermore, it is clearly an issue which needs addressing and one that should not be discounted.

However, there is the worrying potential for miscasting of Georgians in the EU if this pattern of arrests and high representation in crime statistics continues. The Dutch have recently requested for Albania to have its visa-free status revoked (Georgia Institute of Politics, 2019) due to the country’s connection to, and export of, organized crime. There is concern within Georgia that the country could face similar measures (Eurasianet, 2018).

Albanian organized crime is different to that of Georgia, and is indeed not born out of the Thieves-in-Law honour code. It is highly regionalized and inflated by geographical circumstances - Albania often acts as a transfer ground for human, weapon, and drug trafficking between North Africa, the Middle East and Europe. However, while the crime originating out of Albania is separate to and different from that of the Georgian Thieves-in-Law there are important similarities to consider in how these issues are perceived.

Albanian organized crime has systematically pushed “Albanian Mafia” headlines (see The Guardian’s: Kings of cocaine: how the Albanian mafia seized control of the UK drugs trade). This, as is the case with Georgia, creates a false perception of the issue. Albanian organized crime is a significant issue and has caused incredible damage to many, however, invoking mafia imagery misrepresents the structural sophistication of the groups carrying out these crimes (theconversation.com, 2018). Albanian organized crime is carried out by small groups not beholden to some grand Mafia organized crime structure. Georgian organized crime, or, more accurately the Thieves-in-Law operate similarly. Whilst there are strict codes and hierarchies across the criminal world, each thief is usually choosing how they operate and what their own individual goals are. As such, the headlines of the Georgian mafia are misleading in as far as they tie the crime to the country rather than the individual, or at least the Thieves-in-Law honour code. These are criminals who are Georgian, who have been successfully reformed out of the country from which they previously- or their relatives/friends, operated.

Conclusion

Understanding the nuance and history of the criminal network that emerged out of the former Soviet Union is important to comprehending the arrests of Georgians that have been occurring across the EU. The overrepresentation of Georgians in European crime statistics is seemingly a by-product of the success of the internal reforms that have taken place within the country. There is evidently actions which can be taken to improve the control over Georgians who still hold links with Thieves-in-Law that have left the confines of the country, as there can be further measures taken to curb organized crime within Georgia itself, to suggest it has been completely eliminated would be incorrect. However, the linking of Georgia to organized crime in the EU as a means to delay the accesension process or potentially revoke visa-waivers would mischaracterize Georgia to much of the European public. Georgia is an example of a country which has adopted many successful reforms on this issue, not the opposite. Holding up the remnants of the criminal legacy of the 1990s as reason for delays in Georgia joining the EU is seemingly an example of extreme bureaucratic cruelty given the fact that Georgia’s efforts on addressing the issue internally have been noted for their success.

See Also

Georgian Bishop Accuses Government Official of Plotting Assassination; Opposition Leader Alleges Husband’s Abduction

Armenian Government and Church Face Growing Tensions Over Leadership Allegations

Tensions Rise Between Russia and Azerbaijan Over Medinsky’s Ukraine Conflict and Karabakh Remarks

Chechen Official Outlines Conscription Rules for Russia-Ukraine War