Searching for Georgia’s Place in Biden’s Vision for Eastern Europe

As some crucial aspects of the Biden administration’s vision toward Eastern Europe are being rolled out, Georgia’s precarious geopolitical position is important to watch. Tbilisi seeks Washington’s attention, but it also fears that a radically increased American military support could invite Russian reaction. Being left out of Western support will bode ill too. It is these dilemmas which (de)motivate Georgia’s political elites. Perhaps consistency from Washington is what will bring benefits for Tbilisi as America’s smaller scale, but persistent political and military moves could prove far more effective.

The US president Joe Biden’s policy towards the Eastern Europe is gradually shaping up. The recently held summit of the Bucharest Nine, a group of countries on the eastern edge of NATO – Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, and Slovakia – joined by the president himself, NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg indicated that the Eastern European NATO states would play a far greater role in Washington calculus when it comes to Russia and the Black Sea security. It also means that those states would like to see a bigger NATO military presence on the bloc's eastern flank.

Ukraine is in the spotlight. "As allies on the Eastern flank, we need to continue consolidating deterrence and defence. We all recently witnessed the worrying military build-up by Russia in our close neighbourhood, in the Black Sea, in and around Ukraine," the Romanian president announced during the summit.

Biden aims to restore the US credibility in the region shattered during Trump’s presidency. Credibility comes because of political consistency which should be shown not only through public statements (though its importance is at times underestimated), but also with real political, economic, and military actions. Support for Eastern Europe cannot be as decisive as to cause a sudden upending of the regional balance of power. This would most certainly cause effective counteractions from Russia in the age when the US cannot afford spending too much time and resources on the European front considering growing geopolitical and geo-economic challenges posed by China in the Indo-Pacific region. And this is where political consistency is important, as small but consistent support for Eastern European states matter and were often glaringly absent in the Trump period.

Biden is very familiar with Poland, Ukraine and Georgia. He served as senator and vice president to Barack Obama and knows the threats the Eastern Europe vulnerable to and that those states are among most devoted US partners and allies. Support for the eastern flank ranging from Baltic to the Black Sea is not only about defending pure democratic and liberal ideals of those fledgling democracies, but more so about the geopolitics of the Europe and Eurasian continent. Allowing Russia to undermine Ukraine would increase Moscow’s projection of power. More concretely though, it would create a highly unstable grey zone (geographically extending to the heart of Europe) and where Russian military penetration occasionally could take place.

US actions are likely to include consistent sending of troops battalions to the eastern flank, occasional patrolling of the Black Sea, and visits by high-ranking American officials to the region. More importantly, however, the US is likely to pay larger attention to Ukraine. During his recent visit to Kyiv the US Secretary of State Antony Blinken announced Washington could increase security assistance to the war-weary country after what he called Russia's "reckless and aggressive" actions by massing troops near the Ukrainian border. "I can tell you, Mr President, that we stand strongly with you, partners do as well. I heard the same thing when I was at NATO a couple of weeks ago and we look to Russia to cease reckless and aggressive actions,” Blinken said in a public appearance together with Zelenskiy. To underline Ukraine’s importance, the visit came at the sensitive time of increased tensions between Kyiv and Moscow over the latter’s military build-up along Ukraine’s border and in the occupied Crimea.

Further east in Georgia is gloomier. The dominant perception is that the country is being left out of grand strategic developments in the Eastern Europe, namely the US’ growing attention to the region as a whole and Ukraine in particular. This might be due to the still ongoing internal political troubles Georgia has been experiencing for the past several months with some of the opposition forces continuing to boycott the legislative following the 2020 parliamentary elections. The country’s political leadership was too immersed with the intra-party politics which could have made it miss latest developments in the Eastern Europe.

All hopes now lie on Biden himself and his administration, crucial members of which are quite familiar with Georgia’s problem of territorial integrity and Russian military aggression. As decoupling the Ukraine issue from a quite similar Georgian problem will be difficult, some brighter scenarios could be discerned for the future US policy toward Georgia.

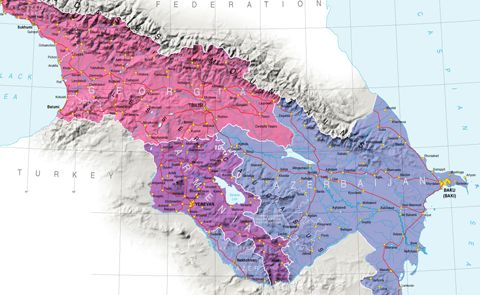

Georgia’s territorial problems due to the Russian military presence in Abkhazia and Tskhinvali Region (the latter also known as South Ossetia) will remain a major obstacle for the country’s NATO membership. Moreover, Russian military moves in the South Caucasus, particularly in the wake of the Second Karabakh War, could serve as a major disincentive for the US and NATO overall to make a major expansion step in the region.

But under Biden various models of alliance membership will be proposed. Among them will be the non-inclusion of Georgia’s troubled territories under NATO defence obligations, thereby extending the collective defence article solely over those territories under Tbilisi’s control. Biden will be more straightforward in his vision of future bilateral ties with Russia, and his administration will certainly be more principled towards Moscow, it is also clear that Biden is unlikely to seek further complications with Russia. The latter’s military presence in Georgia’s Abkhazia and Tskhinvali regions will often be invoked and criticised by the US official, but it remains to be seen how far Washington is able to go regarding Georgia’s NATO membership prospects.

This however does not mean that consistency will not be present in the US foreign policy. Perhaps what could happen is the introduction of an enhanced NATO-Georgia partnership involving more regular military training, transfer of military technologies, etc. Under Biden Georgia will continue to serve as crucial partner in the region allowing America to influence the corridor leading to the Caspian Sea, thus penetrating in the middle of Eurasia.

And last, the Georgia and Ukraine problems should be placed within the wider Eurasia context of shifting US attention from the Middle East and parts of Europe to the Indo-Pacific region. As is the case with the Eastern Europe flank, this does not mean that US foreswears its attention or obligations toward the region. But it does, however, indicate that Washington will be increasingly occupied with the other problems – raising tensions with Moscow over Ukraine’s and Georgia’s NATO membership at this moment might not be the foreign policy line to pursue at this time.

Emil Avdaliani is professor at European University and the director of Middle East Studies at Georgian think tank, Geocase.

See Also

3+3 Initiative as a New Order in the South Caucasus

Economic Cooperation Between Armenia and Georgia: Potential and Challenges Ahead

Russia and Occupied Abkhazia: A New Type of Relations

Georgia and US: From Close Ties to Caution