Armenia and Azerbaijan Prepare For a New Major Confrontation Amid Russia’s Failure in Ukraine

On September 28th, Armenian and Azerbaijani forces were engaged in public accusations of violating a tenuous ceasefire, resulting in the death of three Armenian soldiers and wounding for Azerbaijanis. As Azerbaijan’s tactics become increasingly coercive, it is unlikely to see a quick solution to the problems in bilateral relations. With further postponement of the peace treaty signing, the fighting between the two will resume with new intensity. At the same time, Russia will remain preoccupied with Ukraine, which will limit its ability to manage rising tensions in the South Caucasus.

The fighting follows the early September clashes initiated by Baku and which led to the killing of up to 300 people on both sides and, reportedly, the occupation of nearly 50 square kilometers by the Azerbaijani forces. The fighting marked a new turning point in the long-simmering conflict between the two South Caucasus rivals. Azerbaijan attacked the cities deep within Armenia, the territories which are far detached from the usual conflict zone of Nagorno-Karabakh where the two sides fought two wars from early 1990s.

The Azerbaijani leadership presses for advantages as it feels confident the geopolitical situation in the region strongly favors its agenda of reinstating full control over the internationally recognized territory, which includes Nagorno-Karabakh itself.

First, Azerbaijan sees their opposition from the EU, which in July signed a deal with Baku on doubling natural gas imports by 2027 and eventually increasing the inflow to 20 billion cubic meters by the late 2020s.

Another area of increased cooperation with the EU is the nascent Middle Corridor, the route from Turkey/Georgia to Central Asia. This is poised to serve as an alternative to the Russian corridor, which is facing restrictions amid Western sanctions.

Azerbaijan is also feeling confident in its bilateral relations with Russia. Though the two have disagreements over the role of Russian peacekeepers stationed in the truncated Nagorno-Karabakh area as a result of the November agreement that ended the second Nagorno-Karabakh war in 2020, the two sides have learned how to deconflict. Moreover, Baku and Moscow are also allies as they signed in February, just before the invasion of Ukraine, an agreement on expanded cooperation. This covers nearly all sorts of state-to-state relations, but most of all, it has soothed Moscow’s fears of Azerbaijan tilting disproportionately toward Turkey.

Since the war in Ukraine began, Azerbaijan’s role for Russia has also increased due to Moscow’s search for new transit and trade routes. One of them is the International North-South Transit Corridor, linking Russian Baltic ports with Iran and India. As Azerbaijan is set to be a major connector, the Kremlin might have been less willing to obstruct, even if it sent stark warnings to Baku amid the fighting.

Armenia-Azerbaijan tensions cannot be decoupled from Yerevan’s unstable relations with its security guarantor, Moscow. The latter’s position toward the recent escalation in the South Caucasus has been ambivalent. Officially the Kremlin does not support either side, but politicians in Yerevan are worried that Moscow is tilting toward tacitly supporting Baku. Much of Russia’s “Armenia policy” depends on the internal political situation in the South Caucasus republic. It seems that Moscow remains highly uncomfortable working with Pashinyan’s government and it further undermines trust between the two states.

Azerbaijan-Armenia tensions also cannot be separated from Russia’s war in Ukraine. Preoccupied with its prolonged campaign, Moscow has over the past month experienced major defeats on the battlefield. It has partially withdrawn forces from the South Caucasus bases, including the peacekeeping troops in Nagorno-Karabakh, and Azerbaijan may well have tested the boundaries of Russia’s ability to respond simultaneously on several fronts.

Indeed, the fighting in the South Caucasus coincided with the successful Ukrainian counteroffensive around Kharkiv, Putin’s visit to Samarkand for the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) summit, and Tajikistan-Kyrgyzstan heavy fighting.

Armenia appealed to the 4th collective defense article of the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) but received only a muted reaction. The grouping decided only to send a fact-checking mission a week after the ceasefire. Moscow’s calculations are unclear as the failure to support Yerevan causes anti-Russian sentiments in Armenia. Yet, Yerevan has little room for maneuver and Russia knows it. Additionally, Azerbaijan has excellent relations with Belarussian and Kazakh leaders, which limits CSTO’s quick reaction.

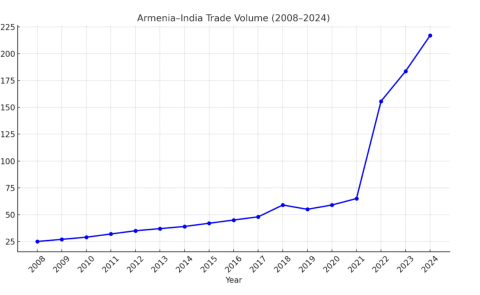

Azerbaijan’s strategy seems to be to push for as many concessions from the Armenian side as possible. The balance of power favors Baku, and this cannot continue for a long period of time. Much will depend on the situation in Ukraine and Russia’s willingness to tolerate Azerbaijan’s aggressive moves. Moreover, in Armenia itself, preparations for a longer-term conflict are in full swing. Yerevan has just announced a 47 per cent increase in the military budget from 2023. India also agreed to sell Armenia military equipment worth $244 million, boosting the embattled country’s military reserves.

At the core of Azerbaijan’s demands is pushing Armenia to recognize Nagorno-Karabakh as a part of Azerbaijan. Armenian PM Nikol Pashinyan seemed to agree with this proposition by making ambivalent statements that for Yerevan it is crucial to secure the rights of Karabakh Armenians and not the territory itself.

The second major Azerbaijani objective is about connectivity. Ensuring the link between Azerbaijan proper and its exclave of Nakhchivan was one of the most important clauses in the November 9 agreement. Turkey and Azerbaijan push for its realization, while Armenia is understandably cautious. Baku seems to be pushing for some kind of extra-territoriality of the route through the Syunik region, which will limit the Armenian state’s ability to impose checks on the goods transiting its internationally recognized territory.

Russia is to gain from the opening of the route as it will be able to control it through imposition of its forces. The November agreement presupposes Russian involvement. However, Russians may also feel uneasy because the reestablishment of connections will further diminish Armenia's sovereignty and strengthen the Turko-Azerbaijani alliance.

Thus despite promises of reaching a long-lasting peace, the trends on the ground indicate that Armenia and Azerbaijan are entering a new period of heightened competition. Maintaining military balance will be crucial as much as what happens in Ukraine where Russia’s position is increasingly untenable.

Emil Avdaliani is a professor at European University and the Director of Middle East Studies at the Georgian think-tank, Geocase.

See Also

Armenia and India: Building New Bridges in Trade and Strategy

Between Tehran and Tel Aviv: Azerbaijan’s Neutrality Dilemma Amid Rising U.S.-Israel Tensions with Iran

From Neorealism to Neoliberalism: Armenia’s Strategic Pivot in Foreign Policy After the Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict

Georgia and Russia: New Turn in Bilateral Relations