Elusive Connectivity in the South Caucasus

After the war in Ukraine, Russia’s policies in the South Caucasus will see tremendous changes. So will the fate of connectivity which has been facing wide-ranging obstacles since the 2020 Armenia-Azerbaijan war. Moscow’s excessive emphasis on the military component in formulating its approach toward the South Caucasus will continue hindering the realization of the railway projects.

World attention is on Ukraine and the barbarity of Russian invasion. The repercussion from the war will be colossal for the Black Sea, European security, and indeed the world order which has been troubled over the past years with disagreements in the Western camp. The Russian invasion changed the landscape. Putin’s war plans produced just the opposite of what he wanted: a more unified West than ever before.

This is bound to have a wide ranging influence on the South Caucasus where the geopolitical situation was tenuous well before the war in Ukraine began. Armenia and Azerbaijan have been adjusting to the new reality following the second Nagorno-Karabakh war. One of the critical elements of the November 2020 ceasefire deal has been the revival of Soviet-era railways and construction of new connectivity lines. With nearly year and a half now passed it is difficult to avoid the sentiment that the connectivity projects are either being stalled or progressing suspiciously slowly indicating that the outside influence might be intentionally prolonging the process.

Russia’s position has been decisive all along. With the collective West sidelined, Moscow and to a certain extent Ankara are the major arbiters of the post-2020 conflict situation between Armenia and Azerbaijan. Opening railways is directly tied to the issue of building a long-term peace in the South Caucasus. But it is easier said than done. For Russia it is the geopolitical component of its peace-building initiative which undermines the prospects.

A long-term peace requires genuine political willingness and unblemished leadership. Russia as a power lacks these qualities. As a result, instead of a more stable and prosperous South Caucasus, continuous border skirmishes undermine this expectation. This quite naturally lessens the level of trust between the two rivals and creates a more unstable security environment in the region overall. The net result is a continuous postponement of the connectivity revival. Moreover, even if meaningful progress (actual opening of the railways) on the issue is eventually reached, a quick and smooth operation of the new trade corridors is unlikely.

This lack of trust is a major challenge. Another problem is Russia’s illiberal peacebuilding methods which are likely to fail to produce real security, largely because the Kremlin is widely seen to have little incentive to have a real peace and instead, prioritizes its own geopolitical interests. Adherence to a peace agreement would negate the instability Russia wants to use to its benefit. The continuous tensions between the two countries makes Russia the winner.

Although victorious in the war, Azerbaijan’s political elites fear a continuous Russian military presence on Azerbaijani soil beyond 2025, when the first term of the peacekeeping mission officially ends. Indeed, the likely extension of Russia’s military presence would drive Azerbaijan to balance it with closer ties with Turkey. Both countries have been allies for decades, but this reached a qualitatively new level with the Second Nagorno-Karabakh war when Turkish military assistance was key. To offset Russian influence, Azerbaijan and Turkey signed the Shusha Declaration in June 2021. The two sides pledged to defend each other in case of an attack on either party. This was a major development in Baku’s foreign policy. Unnerved by growing Russian influence, balancing the northern power with Ankara made sense.

But despite these long-term fears in Baku, Moscow managed to salvage potential deterioration of bilateral relations through the 43-point agreement signed between Azerbaijan and Russia. The document covers cooperation in such areas as external policy and many other areas ranging from culture to economy. One of the stipulations states the two countries should “refrain from any actions that, in the opinion of one of the Parties, damage the strategic partnership and allied relations of the two states.” The growing partnership is likely to help Russia keep its peacekeeping mission in Nagorno-Karabakh beyond 2025. This also means that Baku managed to keep its much-vaunted foreign policy of constant balancing between several bigger powers. But while in the 2000s the West was an actor in Azerbaijan’s calculus, now it is only Turkey and Russia.

Despite these Russian advances, the age of exclusive Russian geopolitical domination in the South Caucasus is nevertheless gradually coming to an end. This partially explains why the revival of the railways has not been realized so far and is likely to remain so, at least in the near future. Indeed, opening the region does not really advance Russian geopolitical goals, which are better served with Armenia solely connected to Russia via Georgia, while denying Azerbaijan a direct line with Turkey.

For Russia, geopolitical calculus is a real motivator in the South Caucasus. Indeed, neutralizing the blocking potential of the Caucasus mountains has been at the heart of Russia’s military efforts. And it can be suggested that if Moscow sees a real advantage in the revival of the railways, it is linked to military matters more than to trade. After all, Russia and Turkey are freer to trade via the Black Sea than through the rugged and geopolitically unstable South Caucasus.

Thus, Russia’s ambivalent position or rather the lack of willingness to facilitate the opening of the South Caucasus generates tensions and deep mistrust in Baku and Yerevan as to what Russian long-term interests in the region are. A transactional approach will likely continue to dominate Moscow’s relations with Armenia and Azerbaijan. But it could be also suggested that after the invasion of Ukraine, Russia’s foreign policy toward its neighbors could experience fundamental changes. It could become more stringent limiting the space for maneuvering. For the latter, the allied ties with Armenia take no precedence over Azerbaijan-Russia relations. Thus, the geopolitical ingredient helps Russia navigate the conflict, be a major powerbroker, but it in no way secures a long-term peace in the South Caucasus so needed for carrying out region-wide railway projects.

Emil Avdaliani is a professor at European University and the Director of Middle East Studies at Georgian think-tank, Geocase.

See Also

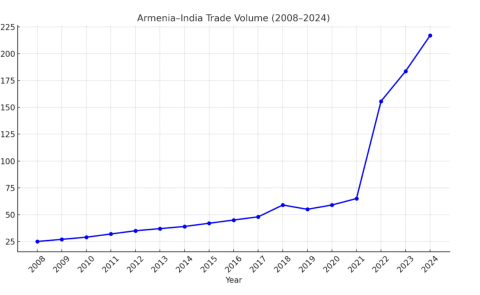

Armenia and India: Building New Bridges in Trade and Strategy

Between Tehran and Tel Aviv: Azerbaijan’s Neutrality Dilemma Amid Rising U.S.-Israel Tensions with Iran

From Neorealism to Neoliberalism: Armenia’s Strategic Pivot in Foreign Policy After the Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict

Georgia and Russia: New Turn in Bilateral Relations