EU Mediation between Armenia and Azerbaijan: Prospects and Challenges

Initially a marginal actor in the Nagorno-Karabakh crisis, the European Union had a brief but intense season as a mediator. It is unclear if and how this season will continue. On the ground, an EU mission remains, along with targeted support interventions for the post-conflict context. Furthermore, a European special representative and different programs and projects signal the European presence.

EU in the Process

When the first Karabakh war erupted, the European Union was still the European Economic Community. The level of European political integration was very limited, and if attention was turned to wars and instability in the East, the focus was on the Balkans, with the dissolution of Yugoslavia and the direct threat to the borders of the then-member states. In thirty years, both Eastern and Western Europe have changed.

Notwithstanding the changes, the role of the European Union in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict remained minor and inconsequential until 2022. The Minsk Group was in charge, and for the EU, entering the region was complicated due to the delicacy of the ongoing processes, and the sensitivities of the parties and mediators demanded caution. The region offers few footholds to the Union, and EU relations with local players besides Armenia and Azerbaijan are complicated. Russia, Iran, and, during the last two decades, Recep Erdoğan's Turkey have not left ample space for external actors and, au contraire, jointly pressed to keep non-regional powers out of local processes.

However, between 2022 and 2023, there has been a certain fragmentation around the post-conflict management of Nagorno-Karabakh. The Minsk Group's system for mediating broke down, and it was not possible to return to a three-way diplomatic solution between Armenia, Russia, and Azerbaijan, which was the last phase of the first Karabakh war. Armenia, in particular, turned into a very mobile pawn. Unsafe in terms of hard security protection and exposed to dire tensions with Russia, its traditional ally, Armenia is most willing to open up to third parties. Azerbaijan pushes for Turkey to be a significant factor in the Caucasus arrangements. However, Baku is also realistically aware that Ankara and Yerevan are not always compatible at the same table. And, indeed, they rarely sit together.

As a result of different needs, therefore, the two belligerents found themselves seeking an honest external broker: someone who could facilitate meetings and at the same time who would not have such pressing interests in the area as to impose their agenda. What they searched for was the key to tackling numerous unresolved issues in a way that both could maximize their positions. The European Union, as a marginal actor in this conflict, especially in terms of political and military activities, met its requisites.

For the Union, pacifying a new hotspot in the wider Mediterranean area is a priority. Moreover, the conflict in Ukraine has made the Caucasus a more relevant priority to ensure the long-term isolation and sanctions regime against Russia without facing shortages of supply routes from the East. Hence, the viability of the so-called Middle Corridor becomes increasingly crucial, along with peace in the South Caucasus and the reopening of all communications, trade, and transport.

In 2022-2023, the European Union was able to play a role as a mediator, with the direct involvement of the President of the European Council, Charles Michel. For the warring parties, the in-between-wars period of 2022-3 was a somehow exploratory year during which they tried various formats. This exploratory process experienced a sudden setback with the one-day war in September 2023. The surrender of Karabakh put an end to the core issue of the territorial integrity of Azerbaijan versus the right to self-determination and independence of Karabakh Armenians. Armenians fled and left Azerbaijan to regain full possession of its entire territory, which is internationally recognized.

Baku is now consolidating its position in the region after a series of military successes, with its shoulders well covered by unshakable Turkish support.From a stand of strength, Baku pushes for a bilateral format of negotiation where Armenia would be in a position of clear inferiority in the absence of an external mediator who is either a supporter of Yerevan or of a fair deal, i.e., not too based on the current balance of power. It is not surprising, therefore, that Yerevan is reluctant to engage in purely bilateral political negotiations. It is open to bilateral technical commissions when this approach is seen as functional for the resolution of tangible issues, such as border procedures or the exchange of prisoners of war.

Baku holds the upper hand to exclude the mediators and one by one, they are cornered. Statements perceived by Azerbaijan as biased become the cause or pretext to halt negotiation formats. Azerbaijan systematically laments that the international community demands strict protections for Armenians and Armenian assets while there were no equal pressures on Armenia to protect Azeris, Azerbaijani properties, and historical heritage, and respect Azerbaijan's territorial integrity during the occupation. These objections are not unfounded but are not very constructive as well. When addressed to the EU, they partially lack diachronic considerations. When the ceasefire ending the First Karabakh War was agreed upon, the EU had existed as a Union for only one year, and it simply would not have been able to formulate an effective foreign policy in an area that was still strictly perceived as post-Soviet, and Russia dominated.

The current EU external action capacities cannot be compared to what they were in the early 1990s. Moreover, for thirty years, the counterpart in administrative management and sovereignty in Nagorno-Karabakh has been an unrecognized authority. This factor, for the European Union as well as for other international organizations, has severely limited the capacity for action. Any form of interaction with de facto authorities could have implied political recognition and required stern cautiousness. Not surprisingly, from 1994 to 2023, only the Red Cross, the dedicated representative of the OSCE, the Halo Trust for demining, and a few other organizations and entities, all with extremely limited mandates, have operated in Karabakh. Now the situation is very different: it is within the framework of Azerbaijan's legitimate, internationally recognized control of Karabakh that requests and objections are being made to Baku.

The Baku official position is that biased statements in favor of Armenia, or, – as Azerbaijan underscores, voluntarily displaced Armenians, are proof of the unreliability of the mediators, whether the European Union or the United States. And therefore, their good offices are not accepted. As soon as the conflict erupted, HR/VP Josep Borrell condemned the military operation and outlined the Union's guidelines: humanitarian access to the conflict-affected zone, implementation of the International Court of Justice's decisions, resumption of dialogue, absolute and non-negotiable recognition of Armenian territorial integrity, and Azerbaijan’s responsibility for the security of the Armenian community. The relations with Brussels have also worsened after French attempts to insert into the negotiation formats the European Parliament's declaration of October 2023, which strongly condemns Azerbaijan and Josep Borrell’s speech at the 25th EU-NGO Forum on Human Rights. Baku is no longer showing up to the EU-brokered meeting. At present, the European mediation season is on standby, at its very best.

The dedicated tools

The Union still has cards to play. Baku is not willing to sever bridges; there is room to keep the dialogue possible, and Brussels is taking steps to keep all doors open. Besides the regular bilateral relations with the counterparts in which the conflict resolution can be more or less prioritized, there are fundamentally two targeted tools at the Union's disposal: the Special Representative and the Mission in Armenia.

Since 2017, the EU Special Representative for the South Caucasus (EUSR) and the Crisis in Georgia has been Toivo Klaar, a diplomat with prior on-the-ground experience in the Caucasian conflicts. He previously served as the Head of Mission for the European Union Monitoring Mission (EUMM), operating in Georgia since the 2008 war. Klaar visited the South Caucasus on September 22, amidst still-smoking cannons, and proceeded to Yerevan, where he met with the Prime Minister, the Minister of Defence, and the Head of the Security Council. The discussions covered the border situation and a detailed account of recent events. Under tight timelines, Klaar then travelled to Baku. In his meeting in the Azerbaijani capital in October, he received positive feedback from the Azerbaijani Ministry of Foreign Affairs regarding a European contribution to conflict resolution.

Klaar has been travelling continuously in the region in recent months, and at the end of November, he visited Ankara to discuss the Caucasian situation and to likely exert pressure on Azerbaijan's strategic partner. In a pre-Turkey trip interview, Klaar expressed support for the Armenian initiative "Crossroad of Peace," recently formulated by Pashinyan. He stated he hoped for a change in the overall context, emphasizing the importance of providing a sense to the populations in Armenia and Azerbaijan that they are in a different world now, a situation where the South Caucasus can truly fulfill its role as a crossroads of peace in both north-south and east-west directions. He noted that this is as important as the signing of a peace treaty, emphasizing the need for a real change in people-to-people feelings and trust. There is indeed strenuous attention towards the signing of the peace treaty, fuelled by speculations about the text being shuttled between the parties but not made public and open to discussion with civil society’s stakeholders and representatives. However, the risk remains that if the tones of mutual acrimony, nurtured for thirty years, do not change, the treaty may end up being just a dead letter. Even more so if the text contains compromises deemed unacceptable by civil society. The EUSR and other institutions are constantly calling for moderation and preparing the local populations for peace, something that is not happening.

The other instrument in the EU toolbox is the EU Mission to Armenia, EUMA. The EUMA mandate involves observing and reporting on the situation on the ground. Additionally, it aims to contribute to human security in the area where it operates. Deployed on February 20, 2023, with a two-year mandate, the mission comprises staff from various EU Member States, including experts and monitors. Recently, the mission declared its full operational capability, and in December 2023, the EU Foreign Affairs Council agreed to increase its presence on the ground from 138 staff to 209. It is headquartered in Yeghegnadzor and operates from six forward operating bases located in Kapan, Goris, Jermuk, Yeghegnadzor, Martuni, and Ijevan. Additionally, there are plans for a Liaison and Support Office in Yerevan. In November, over 1000 patrols were already counted. As per usual practice for missions of this type, personnel on the field become an important and direct source of information during visits by European diplomatic corps, both from Union bodies and from member states that regularly visit the headquarters or the field offices, often accompanying monitors on patrol. In addition to EU member countries, the mission has opened its staffing to Canada. Ottawa has recently opened an embassy in Yerevan, and it is quite active, as it proves its participation in the EUMA.

The agreement signed between the Armenian government and the European Union Delegation in mid-November has confirmed the EUMA’s status in the territory, and it is clear that Armenia is interested in extending the mission's presence and expanding its capabilities. The EU seems responsive to Armenian expectations, while the option of expanding the area of competence of the mission to the Azerbaijani side of the border is at present out of question.

Post-war EU support initiatives

The European Union is actively involved in post-war humanitarian support for the affected population. Following the September 2023 war, Brussels immediately allocated €500 thousand for the affected population as the initial package to complement €1.17 million originally earmarked, reaching a total of €21 million since 2020, when the conflict reignited. In addition to this, the Directorate-General for European Civil Protection and Civil Aid Operations (ECHO) made an extra 5 million euros available for the needs of refugees.

In Granada, Armenia's Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan held meetings with President of the European Commission Ursula von der Leyen and President of the European Parliament Roberta Metsola. Ursula von der Leyen expressed the EU’s solidarity with Armenia. She pledged immediate support. Roberta Metsola emphasized Armenia's need for support in dealing with the humanitarian crisis resulting from people leaving Nagorno-Karabakh. The Commission announced additional emergency and long-term measures to support Armenia, with a plethora of assistance programs and projects. The Commission committed to more than doubling its humanitarian aid, providing an additional €5.25 million in emergency assistance on top of the previously announced €5.2 million. An additional €800,000 would be allocated to the EU4Peace programme, supporting emergency assistance, confidence-building measures, and balanced reporting by media outlets. Under annual programs €15 million should be allocated for budget support to address socio-economic needs and food and fuel purchases.

Discussions with Armenian authorities were initiated to explore urgent technical assistance, utilizing existing programs to address issues such as air safety and nuclear safety. The Commission is working on further support through the Economic and Investment Plan (EIP), including infrastructure assistance, with the potential to deliver up to €2.6 billion in investments. The EIP had already provided €413 million, assisting the Syunik region with social protection and sustainable energy solutions. Brussels supports Armenia's participation in regional projects, including the Black Sea electricity cable project with Azerbaijan, Georgia, Hungary, and Romania. Since Armenia had expressed readiness to receive aid in the form of concrete goods, the EU provided 75 vehicles to enhance patrolling activities. ECHO also allocated funds for displaced persons. In mid-November Yerevan welcomed the visit of the head of Strategic Planning for Crisis Management at the EEAS Directorate for Peace, Partnerships, and Crisis Management, Gil Rostain. On the same day, the EU Foreign Affairs Council decided to investigate the potential for offering non-lethal assistance to Armenia through the European Peace Facility and enhancing the capabilities of the EU Mission in Armenia.

These measures are relevant to address the post-conflict situation, but they also mean something else. They are the proof of an intensification of relations between Yerevan and Brussels. Yerevan is keeping exploring all options, and it is clear it is investing energies and expectations towards the EU. The prospect of a Georgian candidacy would make the EU a far less remote partner, and Yerevan is more than willing to take the chance. On December 11, in Brussels, Minister of Foreign Affairs of Armenia Ararat Mirzoyan participated in the Eastern Partnership Ministerial meeting, where he declared, “My government warmly welcomes the European Commission’s decision to recommend the European Council to open accession talks with Moldova and Ukraine and to grant candidate status to Georgia. This decision is welcomed not only by the government of Armenia but also by the people of Armenia, who also have European aspirations.”

Baku is on the same page, but only to a certain extent. Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev on December 6, 2023 attended a conference entitled “Karabakh: Back Home After 30 Years. Accomplishments and Challenges,” where he very clearly stated: “When Georgia becomes a member of the EU, I'm sure nothing will change in our relations, and also concerning energy cooperation, […] Azerbaijan does not have the target of becoming an EU member in its foreign policy concept for very pragmatic reasons, just because we will never be allowed in. And the reason is also very clear, and we understand it.” He positively assessed Azerbaijan’s relations with the EU Commission, far less positively the relations with the EU Parliament and its President, Roberta Metsola. Charles Michel as well has been harshly criticized by Azeri media and public opinion for perceived pro-Armenian stances. For Azerbaijan, the EU is an economically desirable partner, and the potential to expand bilateral cooperation is huge. Nevertheless, Baku maintains a more selective approach towards the EU and its activities in the regions, expressing clear and loud-increasing reservations about its role in the Karabakh conflict.

Contributed by Dr. Marilisa Lorusso

See Also

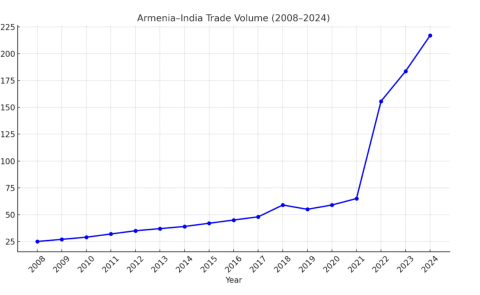

Armenia and India: Building New Bridges in Trade and Strategy

Between Tehran and Tel Aviv: Azerbaijan’s Neutrality Dilemma Amid Rising U.S.-Israel Tensions with Iran

From Neorealism to Neoliberalism: Armenia’s Strategic Pivot in Foreign Policy After the Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict

Georgia and Russia: New Turn in Bilateral Relations