Peace Between Armenia and Azerbaijan Remains Elusive

In the South Caucasus, entrenched distrust and external geopolitical machinations hinder the peace process between Armenia and Azerbaijan. The signing of a peace agreement now seems distant.

Things are once again heating up in the South Caucasus. Nagorno-Karabakh, the region inside Azerbaijan fought over by Baku and Yerevan for more than 30 years, is yet again at the center of regional geopolitics.

On December 13th, it was reported that the gas supply to the breakaway region was cut off and would be restored several days later, which went in parallel with an overall transport blockade from the day earlier, when Azerbaijani officials in civilian clothing blocked the only lifeline – Lachin corridor – connecting Nagorno-Karabakh to Armenia. Locals report that the shortage of food, fuel, and other essentials is already at a critical level but could easily reach a tipping point if the blockade continues. At the time this was written, the blockade continues, and it is difficult to foresee how the crisis will end.

The EU and American officials voiced their concern over the recent developments, calling on Baku to facilitate the resolution of the standoff. The French government called for the restoration of traffic.

This escalation follows Baku’s recent claims that the Lachin Corridor, which has been under the purview of Russian peacekeepers, is used for illegal trafficking from Armenia to Nagorno-Karabakh. Military equipment was mentioned most often, as were allegations that the Armenian side was illegally mining precious material sites. Yet another claim was that the road was used by Iranian nationals to enter Nagorno-Karabakh for illicit business and security activities.

Azerbaijan’s behavior is emboldened by its favorable geopolitical situation. Amid the war in Ukraine, Russia cannot afford another conflict in its neighborhood, which allows Baku to act more assertively. Baku’s moves are also not being met with opposition from the European Union, which, despite the energy decoupling from Russia, needs Azerbaijan’s gas. Moreover, Azerbaijan and Georgia are also seen as vital components in the EU's push to connect to Central Asia in circumvention of Russia.

Baku’s incremental gains on the ground in Nagorno-Karabakh are part of the overall offensive, not only to regain the territory but also to reach a highly advantageous peace agreement with Armenia. The latter has been hesitant to greenlight the final negotiation process. Too many elements, such as potential internal political blowback and the lack of a clear position from Russia, preclude Yerevan from making a decisive move.

The recent escalation is also taking place amid the breakdown of recent diplomatic efforts. The cancellation of the scheduled summit between Armenian and Azerbaijani leaders planned to be held in Brussels on 7th of December was to convene, along the warring sides, Charles Michel, president of the European Council. The Armenian PM Nikol Pashinyan suggested the inclusion of the French president Emmanuel Macron in the negotiating process. Ilham Aliyev reacted by cancelling the summit, citing Macron’s anti-Azerbaijani position.

Yet there are deeper reasons under the growing warring rhetoric, which exacerbates the unfolding crisis. Russia, which so far has suspiciously remained silent, is lurking behind. The present escalation could indeed benefit Moscow. Amid its disastrous war in Ukraine, Russia’s influence in the South Caucasus has been continuously tested by both Armenia and Azerbaijan. Putin was snubbed in Yerevan when Pashinyan refused to sign onto a joint statement made by CSTO member states. Baku has upped its media campaign against Russia because of allegations that Russian peacekeepers do not live up to their mandate. In Baku, many also suspect that the recent appointment of Ruben Vardanyan, a Russian-Armenian billionaire who serves as state minister of Nagorno-Karabakh, is a clear message that Moscow is gradually moving to support Karabakh for Armenians.

Another dilemma Moscow is presently facing is the West's attempts to supplant Russia's leading negotiating position between Armenia and Azerbaijan. The Russian leadership alluded to the existence of two separate peace initiatives. The Western variant advanced by the EU, and supported by the US, urges Baku and Yerevan to recognize each other's territorial integrity, i.e. Yerevan accepting Baku's control over Nagorno-Karabakh.

The Kremlin is obviously sensitive to any such initiatives and reportedly has its own, much different peace project. The latter presupposes continuous deployment of its peacekeeping forces in Nagorno-Karabakh well beyond 2025 when the first term ends, the stipulation laid out in the 2020 trilateral ceasefire agreement reached as a result of the second war over Nagorno-Karabakh.

The continuous tensions between Armenia and Azerbaijan should also be seen from a much broader perspective. It is about deficiencies in how Russia builds a geopolitical order in the South Caucasus. Order reflects a dominant state’s internal structure and geopolitical aspirations, but it also needs to be backed up by other players’ benign intentions. What we see in the South Caucasus is that Russia has grand ambitions but little means to shore up its shattered position. Moreover, increasingly, Armenia and Azerbaijan are unhappy about Moscow’s “peace”. All seek changes, and the result is tragic : the region remains a hotbed of wars, tensions, and shattered peace initiatives.

The collective West should ramp up its efforts to remain a key player in the region. The EU has financial resources, a good diplomatic record, and more benign order-building experience, which set it apart from Russia. Regional states, too, are willing to accept greater Western involvement. As the war in Ukraine is impacting all ties between the West and Russia, the psychological line has been crossed, and contesting Russian influence in the South Caucasus is no longer seen as a red line.

Thus, it is difficult to foresee how the next several months will look in the South Caucasus. Only a few weeks ago, media reports suggested that Armenia and Azerbaijan would sign a final peace treaty by the end of the year. These hopes were dashed with the blockade of the Lachin corridor and mutual accusations. A long-term perspective is nevertheless possible to imagine, and it revolves as much around Armenia and Azerbaijan as it does around Russia. The latter will be much more unwilling to withdraw from Nagorno-Karabakh, which would serve as a perfect recipe for tensions between Baku and Moscow and perhaps a chance for Russia to patch up its troubled ties with Armenia.

Emil Avdaliani is a professor at European University and the Director of Middle East Studies at the Georgian think-tank, Geocase.

See Also

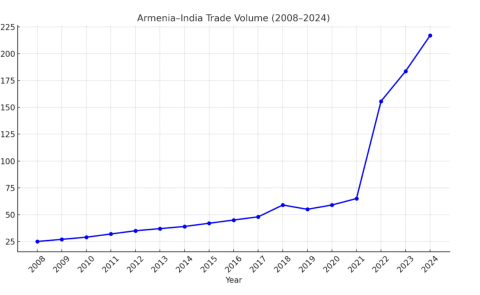

Armenia and India: Building New Bridges in Trade and Strategy

Between Tehran and Tel Aviv: Azerbaijan’s Neutrality Dilemma Amid Rising U.S.-Israel Tensions with Iran

From Neorealism to Neoliberalism: Armenia’s Strategic Pivot in Foreign Policy After the Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict

Georgia and Russia: New Turn in Bilateral Relations