The Blockade of Nagorno-Karabakh and Its Environmental and Social Consequences

About author: Marut Vanyan is a freelance journalist based in Stepanakert, Nagorno-Karabakh.

In addition to humanitarian issues, the blockade of Nagorno-Karabakh (NK) also creates environmental difficulties as Karabakh authorities reported that the water level of the Sarsang Reservoir had dropped too much, which could lead to an environmental disaster there.

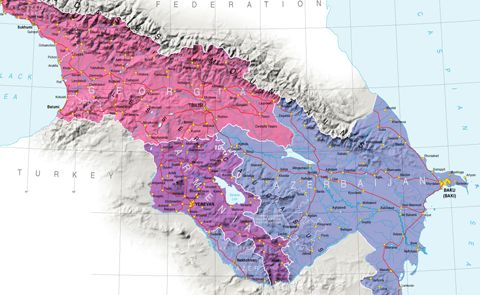

Since December 12 last year, Azerbaijan has blocked the sole road connecting Nagorno-Karabakh to the Republic of Armenia and the outside world through the Lachin Corridor. In April of this year, Azerbaijan set up a checkpoint there. Only the vehicles of the Red Cross and Russian peacekeepers can now enter Nagorno-Karabakh.

During this period of time, the electricity and gas supplies in Nagorno-Karabakh were completely or partially disconnected. The infrastructure from Armenia to Nagorno-Karabakh passes through the Lachin Corridor areas that are officially controlled by Russian peacekeeping troops, but Azerbaijan has actually increased its presence there, violating the November 9 agreement. Since January 9, the electricity supply from Armenia to Nagorno-Karabakh has been cut off. “The wires pass through the territory under the control of Azerbaijan, and they are preventing it from being restored,” said the authorities of Karabakh.

"In the conditions of the 158-day blockade of the Nagorno-Karabakh Republic, since January 9, for 129 days, Azerbaijan has been disrupting the electricity supply from Armenia to Karabakh through the only high-voltage power transmission line passing through the territory under its control. In that way, Azerbaijan is carrying out energy, economic, humanitarian, and environmental terrorism, causing suffering to the Karabakh people, as well as leading to a sharp change in the local microclimate, a decline in underground water resources, and the risk of losing numerous plant and animal species", the Committee of Nature Protection of the NK issued a statement on May 18.

As a consequence, the Sarsang Reservoir hydropower plant's schedule has been overburdened. Due to the dryness of the current year's climate, the reservoir has discharged nearly three times as much water in the last few months compared to the same time period last year, and the water inflow has been nearly half as much, resulting in a 33-meter decline in the level. As of the beginning of May, the water resources of Sarsang have reached the critical limit of about 88 million cubic meters (about 15% of the total water capacity), approaching the dead (unusable) volume of about 70 million cubic meters.

“At least within the past 30 years, the Sarsang Reservoir has never been in a condition like this. Since there was little precipitation in the autumn and winter, we can expect a water-scarce summer,” said Georgy Hayriyan, head of the Karabakh Water Committee, in an interview with Civilnet in March.

Sarsang waters are only used to obtain electrical energy because the reservoir is geographically located in a mountainous area, and then the waters flow to the Azerbaijani plains, where they are used for agriculture. Over the past 30 years, there have always been vicarious accusations between Armenians and Azerbaijanis related to the Sarsang Reservoir. "Due to the Artsakh [Karabakh] Blockade and especially the electricity supply interruption since January 9, 96,000 hectares of Azerbaijani land will not get sufficient irrigation water from the Sarsang Reservoir during the season. We have to largely use those water resources for local production of electricity," tweeted former State Minister of Karabakh Artak Beglaryan.

However, Azerbaijan claims that the Armenian side illegally uses the natural resources on its territory. "Today's claim is a major step in securing justice for the illegal exploitation and expropriation of our energy resources by Armenia. Armenia's theft has resulted in major financial losses for our country, violating international law and our sovereign rights. At no point did Azerbaijan consent to the exploitation of its natural resources," said Deputy Foreign Minister of Azerbaijan, Elnur Mammadov.

The publicist for Caucasus Watch has traveled to the Sarsang Reservoir, which is 60 kilometers from the NK's capital city, Stepanakert/Khankendi, in order to determine the true nature of the image and to gather some input from those who live there. There is almost no traffic on the highway. Due to the lack of petrol and fuel, taxi drivers refuse to drive "long" distances or ask for money. Shortly after the Red Cross vehicle passed by, only the HALO Trust (a humanitarian non-governmental organization that focuses on clearing landmines and other explosive devices left behind by conflicts) field vehicle was parked next to the highway; the crew was performing demining work. During the trip, I saw only these two and a few other vehicles. The regions of the NK appear to be isolated from the capital city.

Arriving at the Sarsang Reservoir, it was observed that the spring rains have only changed the color of the river water, making it murky, and wetted the sand, but the water level has not ascended. "This could be a disaster, not only for our village but for all of Karabakh," - says Ashot Hakobyan, the village mayor of Drmbon/Heyvaly near the reservoir. "Residents of our community do not use water from the reservoir for agricultural purposes because our geographical location is mountainous. People only went there for fishing. Keeping cattle and livestock has become increasingly challenging. They must travel a great distance to provide the animals with water. This is the first time that the water level has dropped so drastically," Hakobyan added.

"You know, this is the only source of electricity in Karabakh. Now, when electricity is not imported from the Republic of Armenia due to the blockade, we have to use water from the Sarsang Reservoir. I am sure that the Azerbaijanis will blame us for the environmental disaster and humanitarian terror because they use these waters for agriculture as well. In my opinion, the consequences are ahead when we have a dry summer. There will certainly be dissatisfaction among Azerbaijanis, and the consequences are unpredictable. Along with environmental issues, the social situation has also become difficult," says the mayor.

According to the Karabakh authorities, as Azerbaijan's blockade of Nagorno-Karabakh continues, at least 3,500 people have lost their jobs and sources of income. 726 business entities, a total of 18% in Nagorno-Karabakh, suspended their activities due to the blockade.

“You know that the Base Metals, gold mining company, operated here, and it was the main workplace for the population in our region. It was the first taxpayer-owned company in Karabakh. About 80 people from our community worked for Base Metals. They lost their jobs. The company compensated for several months but has already stopped doing so. It is true that not everyone can work in the gold mining; it is a very hard job, but people are well paid. What should these people do now? They must begin from scratch.. It was unexpected for everyone. On December 28, 2022, Nagorno-Karabakh's leadership announced that mining operations at a local copper and molybdenum deposit would be suspended due to Azerbaijan's blockade of the sole road connecting Karabakh to Armenia.”

Taking into consideration the unhealthy environment created by the "eco-activists" of the neighboring country [Azerbaijan] and their attempt to mislead the international community, it has been decided to invite international organizations to carry out an ecological expert examination around the operations of the "Base Metals" company. The Karabakh Government, together with the management of the company, has expressed readiness to temporarily halt the exploitation of the mine,” added the statement.

"The social situation of the community is also difficult. After installing a new Azerbaijani checkpoint in the Lachin Corridor, it seems to have become more difficult to import goods. For our community of 380 inhabitants, only 15 kilograms of tomatoes are brought, and most people are unable to buy them because of the limited amount. It is better not to import at all than to buy something one can buy and the other cannot. I don't know what consequences the new checkpoint will have; these are much more political issues,” says Hakobyan.

In April, Azerbaijan installed a checkpoint in the Lachin Corridor, which the Armenian side considers a violation of the November 9 agreement. On May 25, during the meeting between Pashinyan and Aliyev under the framework of Eurasian Economic Union summit in Moscow, Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan announced: "I would like to say that only one corridor is mentioned in this statement - that's the Lachin Corridor, which should have been under the control of the Russian peacekeepers, but unfortunately, it is unfairly blocked by Azerbaijan".

In response, the President of Azerbaijan, Ilham Aliyev, said: "Azerbaijan has not blocked any corridor. Regarding the corridor from Lachin to Khankendi, it is open. On the border between Armenia and Azerbaijan, you acknowledge that there is a border checkpoint there in accordance with all international norms. This border crossing point is 20 meters away from the post of the Russian peacekeeper units."

Anyway, the fact is that buses with civilians don’t go from Stepanakert/Khankendi to Yerevan through the Lachin Corridor, as they did before the Nagorno-Karabakh blockade. Moreover, economic, and ecological problems have arisen.

"Have you seen the condition of the reservoir? There is no water. Just mud and sand. What should people do, look for gold in the sand? There is no such thing, be sure, says Karen Arushanyan (82), a resident of Drmbon village, sarcastically.

"Before the Soviets came to power, we did not have electricity. As a child, I did my school lessons by candlelight, but now it is impossible to live without electricity. We are not a giant country like Russia, whose shores are washed by oceans. This reservoir is the only source of life for Karabakh Armenians. If it dries up in the summer, it will be a disaster for everyone, not just us in the village. Maybe it's easier for us as villagers. We can collect herbs and make Zhingyalov hats (a type of flatbread stuffed with finely diced herbs), but what will those living in the capital do? It will be impossible to live like this; a village cannot survive without a city, and a city without a village,” - says Arushanyan.

Given the drying up of the Sarsang Reservoir and the advent of the hot summer, it can be assumed that the situation will worsen in Nagorno-Karabakh. The local authority has already announced that the NK will experience periodic power disruptions.

See Also

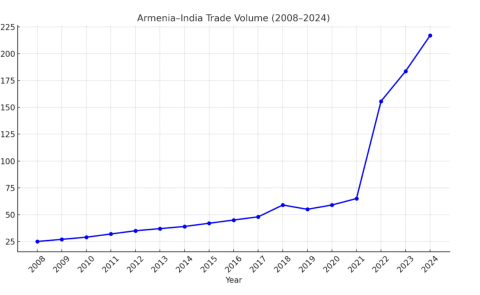

Armenia and India: Building New Bridges in Trade and Strategy

Between Tehran and Tel Aviv: Azerbaijan’s Neutrality Dilemma Amid Rising U.S.-Israel Tensions with Iran

From Neorealism to Neoliberalism: Armenia’s Strategic Pivot in Foreign Policy After the Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict

Georgia and Russia: New Turn in Bilateral Relations