Treading a Tightrope on the Armenian Border: Reviewing the First Two Months of the EU’s New Mission in the South Caucasus

About author: Until recently, Thijs Korsten worked as a Junior Research Fellow at the Institute of Caucasus Studies in Jena (Germany). He is also the Caucasus Regional Editor at media platform Lossi 36.

As the newest ‘kid in town’ in the South Caucasus, the EU Mission in Armenia (EUMA) is finding itself in an increasingly hot context. Although Armenian officials have remarked positively on the mission of around 50 unarmed observers patrolling the international border between Armenia and Azerbaijan, recent Russian and Azerbaijani moves have provided ample cause for concern.

In an unceasing string of negative comments, Russia has voiced its discontent vis-à-vis the EU’s new presence in Armenia. Most recently, Foreign Minister Lavrov has lambasted “undisguised attempts by Western countries to estrange Armenia from Russia” and “undermine the regional security architecture.” Spokeswoman Zakharova, meanwhile, rejected “Yerevan’s attempts to shift responsibility for Karabakh” on the Russian peacekeeping forces in the area.

Meanwhile, Azerbaijan seems relatively undeterred by the EU’s new on-the-ground presence in Armenia, and has opted to put more pressure on the remaining Armenian-controlled parts of Nagorno-Karabakh rather than the international border. The Lachin Corridor linking Karabakh with Armenia has remained largely closed for over 130 days. Between 1 and 28 March, Russian peacekeeping forces reported 17 ceasefire violations in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict zone, compared to 5 in February.

Many observers believe that Baku’s aggressive discourse has been preparing the ground for new warfighting. Defence Minister Hasanov has said that Azerbaijan will respond with “suppressive measures” against Armenia’s supposed attempts to “create fake tension.” On 18 March, Azerbaijan’s President Ilham Aliyev declared that “Armenia must accept our conditions” if Armenians wish to “live comfortably on an area of 29,000 square kilometers.

When a police vehicle of the local authorities in Nagorno-Karabakh tried to use a mountainous dirt road on 5 March to bypass the blockade, a shoot-out ensued which killed three Karabakhi Armenian officers and two Azerbaijani soldiers. On 22 March, an Armenian serviceman was killed in Yeraskh, on the frontline with Azerbaijan’s Nakhchivan exclave.

Events from late March to mid-April pushed the situation even closer to escalation. On 25 March, moments after the EU’s negotiator, Council President Charles Michel, held phone calls with Pashinyan and Aliyev, Azerbaijan’s military used force to suppress roadworks and transportation in the area between Lisagor (Turshsu) and Stepanakert. Baku claimed that dirt roads were being used to circumvent the Lachin Corridor and move military means into separatist-held territory, while Nagorno-Karabakh authorities insisted these mountainous tracks were used for local purposes only.

The following week saw a reconfiguration of road links and military positions in the Lachin Corridor, with Azerbaijani forces constructing a new military post, taking control of strategic heights, ignoring Russian calls to return to their original locations, and seizing land in Armenia around the new road leading from the villages of Tegh and Kornidzor towards Karabakh.

Responding reassuringly, Prime Minister Pashinyan and Armenia’s National Security Services stated that escalations were being avoided and agreements about border positions were being made. But some saw these comments as prematurely downplaying a grave situation.

Russian border guards and peacekeeping troops, and EU monitors work side-by-side in an awkward division of labour. Recent incidents have demonstrated that this situation leaves plenty of grey areas for Baku to exploit as pressuring points in order to coercively pursue its interests in negotiations with Armenia.

According to strategic intelligence firm Stratfor, “Azerbaijan remains unlikely to launch a large-scale military operation to seize large swaths of new territory in Nagorno-Karabakh or Armenia, as less costly methods can enable Baku to maintain progress toward its goals. Each time Azerbaijani forces gain ground, it improves their tactical position — even if those territorial gains only move the de facto line of contact by a matter of meters.”

This analysis was once again shown to be accurate on 11 April. At least three Azerbaijani and four Armenian soldiers were killed in another violent clash, this time near Tegh, and a commander of the Armenian special forces was seriously wounded.

In an ironic twist, the unarmed European observers in Armenia and the armed Russian peacekeepers have begun to look alike, both preventing full-scale warfare but unable to fully contain Baku’s ambitions. The “Russian peacekeepers,” political scientist Nerses Kopalyan commented sharply, “function more like an impotent observation mission than an armed contingent.”

Hours before the 11 April incident, EUMA observers patrolled the area of the Tegh and Kornidzor villages, but they were not present during the open fighting that followed later. According to Russia-leaning former official Artak Zakaryan, the mission’s inability to prevent the clash at Tegh proved its “pointlessness.”

But, although the situation on the ground is volatile and the EU’s mission is indeed limited in its capabilities, it is too soon to write the EUMA off. The mere presence of EU flags on the Armenian border suggests Brussels is slowly becoming willing to indicate ‘red lines’ vis-à-vis Azerbaijan.

EUMCAP vs EUMA: From Prague to Yeghegnadzor

Tasked with patrolling the Armenian side of the Armenia-Azerbaijan border, EUMA succeeds the short-term EU Monitoring Capacity to Armenia (EUMCAP), which consisted of 40 civilian observers, who conducted over 175 patrols from 17 October to 19 December. Dispatched to Armenia in the wake of the escalations of September 2022, the monitoring capacity was a product of quadrilateral negotiations between the leaderships of Azerbaijan, Armenia, France, and the European Council in Prague on 6 October 2022. EUMCAP’s monitors were temporarily drawn from the EU Monitoring Mission (EUMM) in Georgia. EUMA, by contrast, has a two-year mandate and a permanent presence on the ground.

As such, the EU’s presence in Armenia has expanded and become long-term since 20 February. Regular patrolling and reporting yields reliable information to negotiators in Brussels, and provides a “psychological element for the population to feel safer” in the affected border communities, in the words of Deputy Foreign Minister Paruyr Hovhannisyan.

The transition from EUMCAP to EUMA unfolded in an unusually rapid manner. Already before the short-term mission concluded its mandate on 19 December, the EU decided to send a transitional planning assistance team to prepare for a long-term mission. Less than a month later, all relevant EU bodies had discussed and approved the necessary documents and plans. Rarely has the EU been able to complement negotiation facilitation so swiftly with mission deployment and expansion.

With a mandate covering Armenia’s entire border with Azerbaijan, including the Nakhchivan section, it is only logical that the mission will have field offices spread around the country – in Kapan, Goris, Jermuk, Martuni and Ijevan. The mission headquarters in Yeghegnadzor is situated in the ‘narrowest’ part of the country, right at Armenia’s vulnerable north-south link. Although this choice of location could be interpreted geostrategically, the location was rather chosen for practical reasons, to allow for easy access to all tense border areas.

Expanding the EU’s on-the-ground engagement requires concerted effort, which is not always easy to obtain. Some EU Member States were initially wary of alienating Azerbaijan and harming bilateral diplomatic and economic ties, as International Crisis Group noted in a recent report. “If we send a mission only to the Armenian side without Baku’s consent, it may create the wrong impression,” said one EU official quoted in the report. Experts suggest that Hungary was one of the countries which required most diplomatic efforts to be persuaded to agree to EUMA’s establishment. Italy, given its significant energy agreements with Azerbaijan, may also have been reluctant.

With the help of a strong push from Paris the mission has nevertheless been able to go ahead. “Without France, this mission would have been impossible,” says Tigran Grigoryan, a political analyst who heads the Regional Centre for Democracy and Security (RCDS) in Yerevan. France did not keep its support for EUMA a secret. Already in early December, French Foreign Minister Catherine Colonna argued that the temporary mission that resulted from the Prague meeting needed to be extended into a more permanent monitoring presence. Calling EUMA “our eyes and ears on the ground,” French Member of the European Parliament Nathalie Loiseau announced in early February that the mission would include eight French gendarmes.

However, the messages articulated by Chancellor Scholz during Pashinyan’s visit to Berlin in early March seem to suggest that Germany is slowly becoming a ‘runner up’ to France in the strengthening of EU–Armenia ties. EUMA’s Head of Mission, Markus Ritter, is a German police officer with experience in missions in Iraq, Kosovo, Georgia, and South Sudan. Germany is also contributing up to fifteen police officers to EUMA.

Even so, EUMA will not be a merely Franco-German endeavour. The mission has also received active support from smaller EU Member States. Luxembourg, Sweden, Finland, Lithuania, Cyprus, the Netherlands, Austria, Romania, Poland, Portugal and Czechia have all recruited staff for the mission.

EUMA’s planning and launching unfolded within a larger context of deepening diplomatic engagement between the EU and Armenia. Not only did the foreign and security affairs triumvirate Pashinyan–Mirzoyan–Grigoryan meet with senior EU officials involved in the planning and operating of the new mission. On 26 January, the first EU-Armenia Political and Security Dialogue was also held, demonstrating mutual interest in regularised cooperation on security issues.

First EU-Armenia Political and Security Dialogue. MFA of the Republic of Armenia, 26 January 2023.

Monitors in Armenia: Managing expectations

It comes as no surprise that the new European presence has become the subject of partisan discussions in the mission’s host state. While some representatives of Armenia’s post-Soviet ancien régime view EUMA with scepticism, the country’s extremely pro-European extra-parliamentary parties tend to make hasty conclusions regarding geopolitical shifts and promises. “I don’t think it will be an exaggeration to say,” Tigran Khzmalyan, chairman of the European Party of Armenia, told Caucasus Watch in February, “that the EU mission on the Armenian border with Azerbaijan makes Armenia a south-eastern border of the EU.”

Yet, it is important to understand the limitations of the new mission. If the mission alone is assumed to provide safety to Armenia’s border areas, political commentators risk setting the population up for disappointment. There is only so much that 40 to 50 unarmed observers can do on a border of approximately 1000 km.

Expectation management is indeed key, write analysts Sossi Tatikyan and Anna Barseghyan. “EUMA is envisaged to be a small civilian mission that is neither mandated, nor has the capacity to resist any military offensive,” Tatikyan says. In January, various media mistakenly reported that the mission in Armenia would consist of up to 100 or even 200 unarmed observers. But as a matter of fact, the mission is slowly expanding from 50 towards 103 international staff (recruitment is ongoing), and only around half of the staff are monitors.

In this sense, EUMA looks more like a permanent and slightly expanded version of EUMCAP, rather than a mission the size of its sibling in Georgia. “EUMA is a relatively modest mission, significantly smaller than EUMM Georgia,” says Timo Smit, Senior Researcher at the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI). EUMM Georgia has a staff of over 250, and a budget of EUR 47.1 million for a two-year period, compared to EUMA’s 30.7 million.

In his engagement with international and national media, mission chief Ritter has carefully tried to explain what the mission can and cannot do. “We cannot interfere, we only have binoculars and cameras at our disposal,” Ritter told Deutsche Welle. “Many Armenians believe there’ll be a spring offensive by Azerbaijan. If this doesn’t happen, our mission is already a success,” Ritter added. In another interview, he noted that the mission’s current focus is merely on patrolling, visiting local villages, and reporting back to Brussels. Confidence-building, the third mandate component, “is already a matter for the future,” he said.

Although the EU has consistently called for restraint amid renewed tensions both on the Armenian-Azerbaijani border and in Karabakh, EUMA’s public visibility has also been limited. Not only has the mission made it very clear that the Lachin Corridor falls outside of its zone of responsibility, it also does not release any public statements. The mission is required to notify EU Special Representative Toivo Klaar in advance of each patrol, who in turn informs the Azerbaijani side of the EUMA’s weekly schedule to ensure safety. Each week, the mission sends closed reports to headquarters in Brussels.

Armenian security experts agree that the deployment of the EU’s observers on the border constituted a significant foreign policy success on the part of the Pashinyan administration. However, EUMA “certainly cannot be a full deterrent against potential Azerbaijani attacks,” says Grigoryan. “I think this mission is viewed more as an additional tool to increase the costs of a possible attack against Armenia.” Political analyst Benyamin Poghosyan concurs: “The EU mission may play a role of deterrence, but not very strong, and the EU did not send the mission to freeze the conflict.”

Russia, Azerbaijan, and Iran: Managing reactions

With the start of the mission’s first patrols on 20 February, the EU launched “its first full-fledged and long-term civilian presence in a country in a formal security alliance with Russia,” as Crisis Group’s Senior Analyst Olesya Vartanyan described it. Unwavering criticism on the part of Azerbaijan and Russia provides numerous challenges to the mission.

EU monitors will be unable to avoid Russian presence on the ground in Armenia. Russian FSB border guard troops patrol the country’s borders with Iran and Turkey, and have in recent years set up positions in Tegh, Yeraskh, and along the Goris–Kapan highway. Already in January, an EU official noted with concern: “We have had a few cases where [EUMCAP] monitors were turned back by Russian border guards, even though they were accompanied by Armenian Defense Ministry personnel.”

In its recent report, Crisis Group advocated for “some quiet cooperation” between EUMA and Russian forces at the technical level. But the Kremlin has adopted an increasingly hostile position vis-à-vis the mission. Lavrov and Zakharova have said that Brussels is “abusing its relations with Armenia and Azerbaijan,” wants to “push Russia out of the region and weaken its historical role as the main guarantor of security,” and is engaged in “diplomatic raiding” of the negotiation processes.

In spite of the ongoing confrontation between the West and Russia over Ukraine, officials in both Brussels and Yerevan must continue to stress that the civilian monitoring presence is “not directed against anyone.” EU diplomats’ remarks that “Russia is more concerned about [the mission] than Baku” and that “Armenia cannot rely on its traditional partner for security guarantees” may have been insufficiently careful.

Similarly, tactful communication towards Baku remains necessary. Azerbaijan’s attitude vis-à-vis the mission was negative from the start, but initially quite mild. Aliyev called decision to extend EUMCP into EUMA “very unpleasant,” and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs warned that the mission should take into consider Azerbaijan’s interests.

Whereas EUMCAP was planned with Baku’s approval, EUMA went ahead without any Azerbaijani green light. “Baku feels tricked, if not cheated,” explains Rusif Huseynov, director of the Topchubashov Center. “Many in the elite and expert community in Baku feel the EU monitoring mission will help Armenia procrastinate the negotiations just as it had done during the interwar period (1994-2020).”

EU officials have stayed engaged with Baku after the launching of the mission to assuage these concerns. EU representative Klaar has stressed that the mission operates in “full transparency” towards the Azerbaijani authorities. The perception of the mission has nonetheless deteriorated sharply from late February onwards, as evidenced by both official statements as well as rumours and analyses spread by state-affiliated media.

Azerbaijani diplomats say that EUMA has allowed Armenia to take up a “more destructive position” in the negotiation tracks and “cover up its military provocations.” Azerbaijan also denounced mission chief Ritter’s comments regarding the prevention of an Azerbaijani attack, feared by local Armenians, as a “slanderous allegation.”

Certain Azerbaijani media outlets – especially Caliber.az, which is associated with the country’s Defence Ministry – have furthermore alleged the mission to be “not a civilian one, but of a military-intelligence nature.” Connected to NATO and French geopolitical ploys, the mission is claimed to include intelligence officers from other Western states and to provide covert military training to Armenian special units.

Azerbaijani media is working hard to include Iran and anti-Iranianism in narratives about EUMA. On the one hand, EUMA supposedly engages in intelligence activities directed against Iran. On the other hand, however, Azerbaijani state-linked media in February warned that Iranian forces would join Armenia in a sabotage attack. “The main goal of the planned sabotage is to collect evidence for the EU mission about another ‘act of aggression’ by Azerbaijan and the ‘atrocities’ of the Azerbaijani army, as well as organizing another propaganda campaign against Baku in the international community.”

Baku observes Iran’s attitude vis-à-vis EUMA with suspicion. Iran’s Ambassador to Armenia has said his country does not oppose the deployment of European monitors on the border. “The Europeans being there could balance Azerbaijan and that’s in line with Iran’s interests,” Iranian analyst Hamidreza Azizi told Al-Monitor.

Aware that EUMA is only a small and unarmed instrument, Armenia is engaged in a delicate balancing act which does not only involve the EU and US but also relies on India and Iran. Armenia’s Deputy Foreign Minister Vahan Kostanyan has said that “Iranian actions and statements helped to stop a further deterioration” of the September 2022 escalation. However, “unless Azerbaijan actually tries to seize territory in southern Armenia, Iran is highly unlikely to directly intervene in the conflict,” according to Stratfor assessments.

“Armenia should take courageous steps towards Iran, and not be pressured by the US when it comes to arms cooperation,” Yeghia Tashjian told Caucasus Watch. Armenia needs both “a cover against drones” as well as “drones to monitor the border,” the regional analyst added. During the latest skirmish on 11 April, Azerbaijan insinuated that Armenia operated Iranian combat drones, which it does not have – yet. As its global reputation lessens, Baku aims to elevate its strategic importance by portraying Armenia as an Iranian puppet, says RCDS’s Grigoryan.

Civilian Commander Tomat opens EUMA headquarters in Yeghegnadzor. Arsen Torosyan/Twitter, 20 February 2023.

EUMA vs EUMM: Lessons to be Learnt from Georgia

EUMA is not the first European mission patrolling a post-conflict line of contact in the South Caucasus. Since the EU brokered a ceasefire to end the war between Russia and Georgia in 2008, the European Union Monitoring Mission (EUMM) has provided “managed stability” along the unrecognised borderlines that separate ‘mainland’ Georgia from Abkhazia and South Ossetia.

Given that the first short-term mission on the Armenian-Azerbaijani border was staffed by temporarily redeployed EUMM observers, “their knowledge and expertise directly fed into the functioning of EUMCAP and the establishment of EUMA,” explains Klaas Maes, spokesperson of the mission in Georgia.

Much like EUMM provides a ‘hotline’ which connects Georgian, Abkhazian, South Ossetian, and Russian security officials by phone to prevent incidents and escalations in and around Georgia’s conflict zones, EUMA might strive to facilitate a similar mechanism between Armenia and Azerbaijan, as Crisis Group has suggested. “We have a precedent,” notes Tigran Grigoryan. Two hotlines have existed in the context of the Karabakh conflict since 2019, but neither proved durable.

Similar to the mandate of the mission in Georgia, the new mission in Armenia also aims at “contributing to human security in conflict-affected areas.” To this end, EUMM Georgia has three dedicated Human Security teams staffed by experts who track the living conditions in areas affected by the unresolved conflicts. Smaller in size, EUMA is unlikely to contain such teams, although vacancies posted online suggest that it will employ a Human Rights Advisor and a Gender Advisor.

There are other small steps through which the EU can meaningfully contribute to security in Armenia’s border regions. Since 2010, the EU’s monitoring work on the ground in Georgia has been complemented by the Confidence Building Early Response Mechanism (COBERM), an EU-UNDP programme which funds small peace- and confidence-building initiatives. In Armenia, too, the EU could build links between the new monitoring mission and its peace and development programmes. EUMA could also award an annual prize for ‘peace journalism’ like the EUMM does in Georgia, as Onnik Krikorian has suggested.

That said, further similarities between the Georgian–Ossetian–Abkhazian and Armenian–Azerbaijani contexts provide the new mission with less optimistic lessons. In both cases, the lines of separation are subject to militarisation and borderisation, as experts Grigoryan, Vartanyan, Broers, Kopalyan, Toal and Seferian have highlighted. Unrecognised, undemarcated or otherwise contested borderlines are used as instruments by Russian and Azerbaijani forces, respectively, to destabilise, create ‘new realities’, and enforce concessions. Everyday livelihoods in the conflict zones are violently disrupted as a result: villagers can no longer safely access farmlands, schools, water resources, relatives or religious sites.

There is little an unarmed observation presence on the Armenian side can do to replace the illiberal, securitised and coercive strategic pursuits of the Azerbaijani authorities with confidence-building, people-to-people contact, and reconciliation. In this sense, EUMA runs into the same difficulties as EUMM in Georgia, where there is little room to take steps from conflict prevention to confidence-building. Indeed, the mission in Georgia was never granted access to the South Ossetian and Abkhazian sides of the conflict zones, and lacks trust on the part of locals in Tskhinvali or Sukhumi.

Likewise, the mission in Armenia is unlikely to ever be perceived positively by the Azerbaijani side. This does not detract from its overall added value as conflict prevention tool, as some pro-Azerbaijani analysts have misleadingly suggested. Yet, it is perhaps best if EUMA does not become as entrenched as EUMM in Georgia, through endless mandate renewal, and instead paves the way for nationally owned border security. French Eurodeputy Loiseau, too, has said she hopes that “a sustainable peace can be achieved between Azerbaijan and Armenia in less than two years,” so that the mission’s mandate will not need to be renewed

EUMA and the Future of CSDP in the Neighbourhood

The fact that the EU has gone ahead with a mission in the South Caucasus irrespective of Moscow’s reactions “reflects a more self-confident EU,” according to Amanda Paul, Senior Policy Analyst at the European Policy Centre in Brussels. “Russia’s war in Ukraine has underlined that the EU needs to have a bigger security role in the neighbourhood, something that it has resisted for many years,” says Paul.

As the new mission in Armenia enters its second month of operations, the EU is discussing and planning its next civilian mission in Moldova amid growing fears of Russian-orchestrated instability in that country. Already in January this year, the EU’s director in charge of all civilian CSDP missions signalled a turn towards increased on-the-ground engagement in the Eastern Neighbourhood.

According to analysts at the Center for International Peace Operations (ZIF) in Berlin, the rapid step-by-step approach the EU undertook in Armenia – from a short-term redeployment of observers (EUMM/EUMCAP) to a permanent stabilisation actor (EUMA) – “should inspire future crisis management.” Amanda Paul concurs: “The EUMA deployment represents a change of approach and can help to reinvigorate the CSDP.”

But SIPRI’s Timo Smit adds a note of caution: “It is too soon to tell whether the EU and its members can keep up this momentum. The EU and EU Member States have been emphasising for years the need for civilian CSDP to be more responsive and flexible, including the ability to deploy new missions and scale up existing missions quickly. Slow decision making in the Council of the EU and fragmented and decentralised force generation remain bottlenecks. When stakes are high and there is political will among EU Member States, much is possible, but when this is not the case, it will remain difficult to achieve these objectives.”

Whether or not EUMA will live up to local, regional and international expectations will also impact the future of EU missions in the Eastern Neighbourhood. A CSDP mission is a suitable tool for rapid and short-term stabilisation, but ideally needs to be complemented by efforts at a much wider security transformation.

In the short term, Armenia needs to be able to protect its border with a well-coordinated security sector with well-managed defensive capabilities. In the long run, the Armenian–Azerbaijani border needs to be normalised and demilitarised, as the EU hinted at in its most recent statement. It remains unclear, however, how much symbolic and economic capital the EU is willing to invest in this difficult process.

See Also

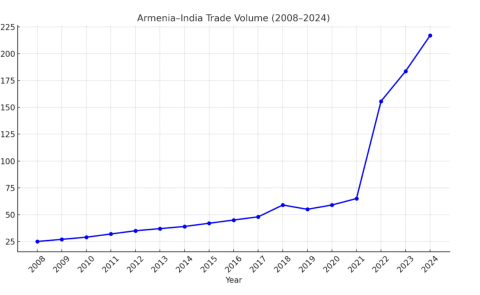

Armenia and India: Building New Bridges in Trade and Strategy

Between Tehran and Tel Aviv: Azerbaijan’s Neutrality Dilemma Amid Rising U.S.-Israel Tensions with Iran

From Neorealism to Neoliberalism: Armenia’s Strategic Pivot in Foreign Policy After the Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict

Georgia and Russia: New Turn in Bilateral Relations