Warming Relations between Georgia and Iran

The multivector foreign policy Georgia is pursuing brings both benefits and challenges. The warming relations with Iran are a positive example of this emerging dilemma, which would require careful balancing on Tbilisi’s part.

Since the end of the Soviet Union Georgian-Iranian relations have never been smooth. They might be more appropriately described as cold and distanced since neither side was particularly open to meaningfully expanding cooperation in political and economic spheres.

To a certain extent, historical memory has played a restraining role on the part of Georgians, with centuries of Persian dominance over Georgia serving as a disincentive to pursue closer ties with the Islamic Republic. Geography too played a significant role. The two countries do not share a common border, and the existing infrastructure running through the South Caucasus is poor enough for a smooth connection between Georgia and Iran.

Then comes geopolitics, arguably the most important factor. Georgia has been pursuing pro-Western foreign policy with the goal of joining the EU and NATO, which is not to Iran’s liking given Tehran’s own difficult relations with the West over its developing nuclear program, confrontation with Israel, and more recently growing Iranian-Russian military cooperation.

This, however, does not mean that the two countries abstained from talking to each other. In fact, there were a few short periods when Georgia and Iran tried to push for closer tourism and trade ties, exemplified by, for instance, lifting of visas for Iranian residents. Yet, the window of opportunity turned out to be short as wider geopolitical imperatives (Georgia’s pro-Western stance and Iran’s closer ties with Russia) hindered prospects for improvements in bilateral relations.

Georgia’s Eurasian Pivot

This period of stagnation in bilateral relations might be coming to an end. Indeed, a new period has begun in the foreign policy of Georgia. It is obvious that the country has embarked on a multi-vector policy. For instance, Tbilisi is no longer fixated on one big geopolitical player and therefore tries to build close relations simultaneously with several big geopolitical centers: the collective West, China, Turkey, and, apparently, Iran.

Another two interesting shifts can be observed in Georgia’s foreign policy. It appears that the official Tbilisi now has a specific priority for promoting its interests and expanding its role in the immediate neighborhood. This replaces Georgia’s decades-long policy of betting on geographically distant players such as the US and the EU. The second notable development is essentially the birth of the Eurasian vision in Georgia’s foreign policy. Along with the geopolitical rise of China and Asia in general, many countries across the continent have launched the so-called “pivot to Asia.” Perhaps today, Georgia is also starting to pursue such a policy.

It is precisely in such a broad geopolitical context that we should see the steps toward careful rapprochement with Iran. For instance, the two recent visits by the Georgian prime minister to Iran – one for the funeral of the late president Ebrahim Raisi and another for the inauguration of his successor Masoud Pezeshkian – are the clearest signs that Tbilisi pushes for warmer ties with the Islamic Republic. Georgia surely is not becoming a pro-Iranian state, but it is likely trying to strengthen relations with a powerful player in the region. This makes sense in a certain manner. Considering the consequences of the second Nagorno-Karabakh war in 2020, Iran has intensified its efforts to increase its influence in the South Caucasus. For this, Tehran has taken several steps to deepen relations with Armenia, whether in economic or security fields. Iran has also taken a series of steps to normalize relations with Azerbaijan, which culminated in the resuming of work by the Azerbaijani diplomatic corps in Tehran.

As previously argued, Tbilisi's multi-vector policy should contextualize the recent warming of relations between Georgia and Iran. In the South Caucasus, where dependence on one big player is often counterproductive, there is a need for constant maneuvering in foreign policy. The Georgian kings accomplished this in the medieval period, enabling them to preserve the country for centuries. Today, Georgia may be pursuing a similar course. Indeed, Georgia is the only country in the region that does not have an official ally. Therefore, implementing multi-vector foreign policy could potentially transform this weakness into a geopolitical advantage.

Though Georgia’s emerging multi-vector foreign policy will be tested in the coming years, it is clear that the country pursues a foreign policy free of ideology: the country's traditional fixation on the West has ended, paving the way for Tbilisi to become more focused on other major players.

However, despite the growing space in Georgia-Iran relations, it remains unclearwhat concrete benefits Tehran could offer to Georgia. The Islamic Republic remains highly sanctioned, and any close financial cooperation could cause the imposition of secondary sanctions on Georgian institutions – a scenario Tbilisi will be careful to avoid. Therefore, Tbilisi must maintain its traditionally close ties with its Western partners through a delicate balancing game. This will be difficult to achieve given the significant deterioration of ties between Georgia and the EU/US. Anyway, the multi-vector foreign policy brings both benefits and challenges for Tbilisi.

Emil Avdaliani is a professor of international relations at European University in Tbilisi, Georgia, and a scholar of silk roads.

See Also

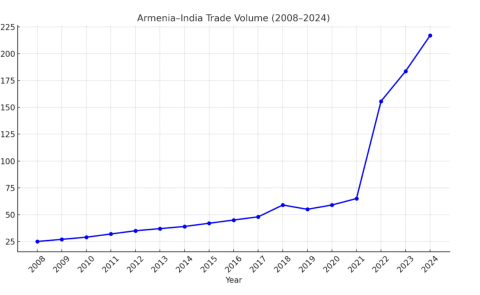

Armenia and India: Building New Bridges in Trade and Strategy

Between Tehran and Tel Aviv: Azerbaijan’s Neutrality Dilemma Amid Rising U.S.-Israel Tensions with Iran

From Neorealism to Neoliberalism: Armenia’s Strategic Pivot in Foreign Policy After the Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict

Georgia and Russia: New Turn in Bilateral Relations