Despite Troubles, Eastern Partnership Will Remain Operational in one form or another

Recently prospects of enlargement of the European Union after the Eastern Partnership (EaP) initiative have notably declined. This happens in the context of the lack of ideas and practical willingness among the EU’s political elites to enlarge the bloc and the fears among the EaP states that little has come out of the initiative overall. On top of this, there are also geopolitical problems: discouragement following France’s opposition to the enlargement in the Balkans as well as Russia’s negative stance towards its small neighbors’ pro-western foreign policy.

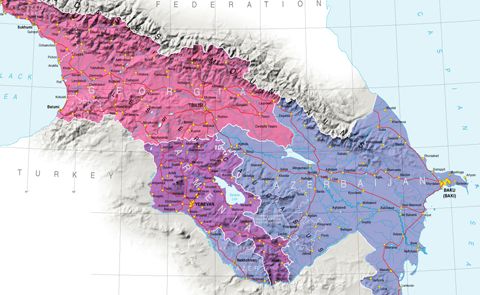

Last year marked 10th anniversary of the Eastern Partnership (EaP) launched by the European Union (EU) with the South Caucasus states, Ukraine, Belarus and Moldova. Though, as explained below, there has been a marked success on many fronts, by 2020 the EaP experiences fundamental ideological and geopolitical problems which significantly limits the EaP members’ EU membership chances in the coming years.

There are large differences in the visions of further European integration among the EaP and EU member states. Since the no membership was offered to the “EaP’s top states” – Georgia, Ukraine, and Moldova – there is a certain exhaustion (fatigue) resulting from the cooperation program (without real membership prospects) at the political and economic level.

A key dividing issue among the EU states is what the further development of the Eastern Partnership’s political dimension should be. Initially it was expected to be the eastern enlargement of the EU. However, this transformed into a dilemma of constant postponements of the EU’s possible enlargement into the former Soviet space could increase frustration among EaP states. This is particularly the case with Georgia which still enjoys deep popular support for EU membership. Additionally, the EU’s limited investment in Armenia, its at times contradictory policy towards Azerbaijan and limited support in the separatist conflicts resolution process ignite frustration among all countries.

There is also a lack of a common vision among the EU countries on the future of the EU enlargement. For many in Brussels, though the implementation of reforms in Georgia, Ukraine and Moldova can be characterized as stable, the expected political goal of EaP policies is unclear as the states remain short of EU membership.

On top of a clear deficiency of ideas among the leaders of the EU-member states on the future of the EU, there is also a markedly diminished political will among EU political leaders to find a solution to the EaP dilemma.

Looking at the problem from a larger perspective, there are geopolitical reasons which limits the EaP’s potential success. As the EU’s relations with Russia remain strained over Moscow’s annexation of Crimea and the war in eastern Ukraine, the EU enlargement into the South Caucasus and Ukraine could further undermine an already weakened security situation in eastern Europe.

Moreover, there is also an ambivalence on behalf of the EU member states. For instance, in October 2019, France torpedoed the EU’s drive to start membership negotiations with North Macedonia and Albania. Though several months later Paris agreed to renew negotiations, but under changed rules, the story adds to the overall skepticism over enlargement amongst major EU states.

The Future of the EaP

Though the EaP experiences troubles at the ideological, leadership and geopolitical level, the fate of the EaP is unlikely to be sealed. It is true that the likelihood of South Caucasus states, Moldova and Ukraine becoming EU members is and will remain quite low in the coming years, but the EaP is likely to continue to operate (possibly under the new initiative) in the next decade. Problems will remain, among which the absence of new visionary ideas among the EU leaders will be the most challenging issue.

Throughout the 2020s geopolitical hurdles regarding the EaP will remain more or less the same as the initiative has faced so far. Russia’s continuous military and economic aid to the separatist territories in Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine will limit these states’ ability to maneuver and closer associate with the EU. As explained above, amid economic and political troubles in the EU, Brussels will remain hesitant to further raise the ante of competition with Moscow over the borderland territories.

Considering that there are no concrete prospects to become the EU members, for the Eastern Partnership members the most realistic sphere for enhanced partnership with Brussels will likely be a larger sectoral cooperation on the development of critical road, port and railway infrastructure, deeper engagement with the local civil society, extended liberalization of markets and an increased level of trade. In turn, these stronger stages of cooperation would inevitably limit Russia’s economic clout in Georgia and other EaP states.

This means that EaP’s future initiatives will likely be confined to the economic, law and social problems. Despite all the criticism swirled at the EaP, the initiative nevertheless managed to achieve notable success in one major and perhaps the most crucial sphere – economy. Over the past decade or so Georgia and some other EaP states’ trade has already shifted to the EU market at the expense of the Russian economic influence. Indeed, some of the EaP members even managed to sign extended European Union Association Agreements (AA) and Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreements (DCFTA), as well as introduce the short-stay visa-waivers.

Overall, it could be argued that though EaP initiative suffers from a lack of ideas about its future existence, geopolitical competition with Russia and France’s and other big states’ indecisive actions, it is unlikely that we would witness a total abandonment of the project. The move will fundamentally undermine the EU’s position among the South Caucasus states (in Georgia the general support for EU membership remains high) and elsewhere across the former Soviet space. It would, on the other hand, increase Russia’s chances to re-impose/grow its economic and by extension geopolitical might on the South Caucasus state, Ukraine, Moldova.

Emil Avdaliani specializes on former Soviet space and wider Eurasia with particular focus on South Caucasus and Russia's internal and foreign policy, relations with China, the EU and the US. He can be reached at emilavdaliani@yahoo.com.

See Also

Armenia's Pursuit of Western Allies in the Wake of the Failed Russian Alliance

Building a New Beginning: Struggles and Triumphs of Armenians from Nagorno-Karabakh

Trade Networks in the South Caucasus: Future Plans and State of Art

The Daily Struggles of Karabakh Armenians in Their New Home