Turkey’s Win-Win Strategy in Nagorno-Karabakh War

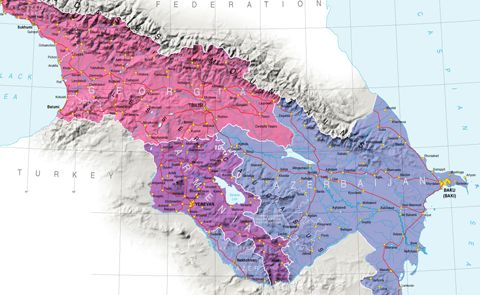

Recently the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict has become an important component of Turkey’s foreign policy. Over the years Ankara’s support for Baku has grown exponentially. This included active diplomacy, but most of all the dispatch of sophisticated weaponry. Growth of support for Azerbaijan has also coincided with Turkey’s more active foreign policy in the Middle East and the Mediterranean. This is strikingly different from Turkey-Azerbaijan relations of the 1990s and even early 2010s. The answer in Ankara’s assertiveness could lie in energy and trade routes.

To be sure, Turkey has always supported Azerbaijan – common cultural and generally geopolitical aspirations propelled their bilateral ties. However, nowadays as Turkey has become more assertive in the Middle East and the Mediterranean, its policy towards the Nagorno-Karabakh has also evolved. Over the past several years there has been a certain tilt towards a more robust Turkish military aid to Azerbaijan. Several factors caused this policy change. First is the energy flow. As Turkey’s consumption market increases, Azerbaijan has gradually moved to become its major gas supplier. In the first half of 2020, Turkey imported 4 527,39 cubic meters of Azerbaijani gas, which is some 20,4 percent more in comparison to the same period of 2019. On the other hand, the import from Russia diminished by almost 62 percent compared to the same month in 2019. In May 2020, Azerbaijan officially became Turkey’s top gas supplier.

This became possible after the launch of TANAP in late 2019. The $6,5 bln. project is essentially a part of the $40 billion Southern Gas Corridor with a number of pipelines connecting Azerbaijan’s Shah Deniz II field to the vast European market. TANAP has the capacity to transport up to 16 billion cubic meters (bcm) of Caspian gas per year: 10 bcm go to Europe and 6 bcm to the Turkish market.

Geopolitical thinking perhaps is at play as Turkey has always been worried that aspirations in the South Caucasus and elsewhere could make the country vulnerable in regards to its dependence on Russian gas. Indeed, as differences with Russia in Libya and Syria persist, Turkey has turned its attention to alternative ways to reduce its dependence on Russian gas. This creates a perfect opportunity for Azerbaijan to enhance its position as the region’s major gas supplier and thus further seek support in the ongoing Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. Turkey, on the other hand, is interested in an unhindered flow of Azerbaijani gas and, as other regional or global powers, is willing to show it would defend its gas supply chain politically and, if necessary, even use a limited military force.

This could explain Turkey’s assertiveness in the July 2020 fighting between Armenia and Azerbaijan. The violence took place in the Tovuz district of Azerbaijan, far from Nagorno-Karabakh, which is usually a centre for either large-scale fighting (as in 2016). What relates the fighting in Tovuz to the geopolitics of gas supplies is the region’s location as a vital land corridor for regional transport and energy export routes such as the Baku–Tbilisi–Ceyhan (BTC) pipeline, the South Caucasus natural gas pipeline (SCP) and the Baku–Tbilisi–Kars (BTK) railway. This infrastructure is part of a larger trans-Eurasian East-West corridor that has been championed by the West since the end of the Soviet Union. But more importantly the corridor allows Ankara to seek an alternative to the dependence on Russian gas. Therefore, any military moves near those strategic routes would invite harsh Turkish action.

Indeed, following the July fighting Turkey’s defence industry chief stated the country was ready to help its eastern ally. Joint military drills in Baku, Nakhchivan, Ganja, Kurdamir and Yevlakh followed. The message was clear – active Turkish military involvement in the region might follow if a threat is posed to the pipelines.

Thus, Azerbaijani gas is set to play a central role in Turkey’s evolving approach towards Azerbaijan and the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict overall. The increased Turkish support for Azerbaijan was also clearly visible in the September-October war between Azerbaijan and Armenia. Turkish-made drones were spearheading Azerbaijani attacks and Ankara was also most likely providing infrastructure and support for the weapons. According to Erdoğan, Ankara’s support for Azerbaijan was part of Turkey’s quest for its “deserved place in the world order.” It fits into the overall pattern of the country’s foreign policy in the Middle East and the Mediterranean.

Similar to the other regions, the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict has turned into an opportunity for Turkey as the major world powers are distracted by internal matters, the resurgent pandemic, ensuing economic problems and most of all lack of active leadership. Turkey has been openly pushing to alter the existing status quo over Nagorno-Karabakh. In Ankara’s opinion, for decades France, the US and Russia have led international mediation efforts to no tangible result as Yerevan has retained control of the enclave and adjacent territories. No wonder that when the leaders of France, Russia and the US jointly called on Armenia and Azerbaijan to cease fighting around the disputed territory of Nagorno-Karabakh, Erdoğan criticised the Minsk Group.

Ankara is also betting that, despite their differences over Nagorno-Karabakh, Turkey and Russia, would be able to find a lasting solution to the conflict. One important aspect will be Turkish involvement in the peace resolution. Turkish leadership already hinted at this scenario when Cavusoglu announced readiness to work together with Russia to resolve the Armenia-Azerbaijan conflict.

Indeed, Russia-Turkey cooperation mixed with intense competition has been a hallmark of their bilateral relations of the past several years. Despite tensions, they can work out durable solutions as the case of north Syria shows. More broadly, they cooperate to side-line Western powers whether it is in Syria or in Libya. A similar trend is emerging around Nagorno-Karabakh. Russians also expressed readiness to cooperate with the Turks to de-escalate the tensions.

The emerging trend of Russia-Turkey cooperation/competition around Nagorno-Karabakh could be yet another theatre where a remaining Western negotiating influence could disappear. Russia and Turkey could be aiming at the condominium management of the conflict, similar to the Black Sea management model advanced by Ankara after the Cold War, where Turkey and Russia would be decisive powers. It could be also similar to how both powers brokered a relative peace in Syria by altogether side-lining Western powers.

True that so far as a dominant military power in the region, Moscow has served as a major negotiator between Baku and Yerevan. During 2016 fighting, the Kremlin intervened after the fourth days of intense clashes. The Kremlin’s leading role was underscored on October 9 by its latest diplomatic master stroke when in a day the foreign ministers of Azerbaijan and Armenia were invited to Moscow and came up with a ceasefire (however shaky it remains so far).

Moscow has always tried to keep a military balance between the two South Caucasus states. Another advantage is the presence of Russian military base in Armenia, near the Turkish border. Therefore, the Turks are hesitant to make major military moves not to disturb Russia’s top priority: the maintenance and defence of the existing regional status quo in the South Caucasus. This would mean that the Russians ideally could negate active involvement of any foreign power.

Though it still remains to be seen how far Russians would go in tolerating the emerging Turkish involvement in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, Moscow also sees that keeping the status quo between Armenia and Azerbaijan has become untenable. First, militarily Azerbaijan is more preponderant through extensive decades-long growth of military budget. Second, Turkish military aid to Baku and general diplomatic support pulled the two states even closer. If Turkey is denied a negotiating role and Azerbaijan is not given some territories back, Ankara could ramp up its military support for Baku potentially sparking another military standoff. Perhaps Moscow’s biggest fear nowadays is that efforts to keep the same status quo would risk alienating Azerbaijan further away from Russia and moving it closer to its Turkic kin and perhaps the West in general.

In the end, for the Kremlin, Azerbaijan is no less important geopolitically than Armenia. Various hints in the Russian media indicate that a shift in Moscow in favour of a new balance of power around Nagorno-Karabakh conflict is taking place. So far without Ankara’s presence, but it still will be a win-win outcome for Erdoğan.

Emil Avdaliani, non-resident fellow at the Georgian think tank, Geocase, specializes on wider Eurasia with a particular focus on South Caucasus and Russia, relations with China and the US. He can be reached at emilavdaliani@yahoo.com.

See Also

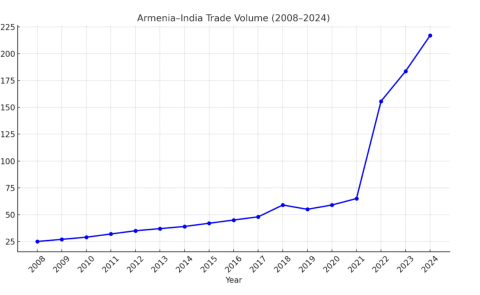

Armenia and India: Building New Bridges in Trade and Strategy

Between Tehran and Tel Aviv: Azerbaijan’s Neutrality Dilemma Amid Rising U.S.-Israel Tensions with Iran

From Neorealism to Neoliberalism: Armenia’s Strategic Pivot in Foreign Policy After the Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict

Georgia and Russia: New Turn in Bilateral Relations