Russia’s Balancing Game around Nagorno-Karabakh

Azerbaijan’s military success around Nagorno-Karabakh changes the entire balancing game Russia has pursued since 1994. Moscow will either have to adjust to the new reality, a likelier scenario, or it risks antagonizing Baku, which will in turn invite greater Turkish influence in the South Caucasus.

As the war between Armenia and Azerbaijan shows signs of Baku’s military superiority and significant territorial gains, Russia has limited options to regulate the conflict. By attempting to force Azerbaijan into a cease-fire that would guarantee some former Armenian territorial advantages or even most of them, Moscow could face growing resentment in Baku and what matters even more is its decisive tilt towards an already influential Turkey.

The change in the balance of power between the two South Caucasus states was years in the making. Azerbaijan had a decades-long program of re-arming its army for an eventual clash with Armenia. Russian, Turkish and increasingly Israeli military supplies propelled Azerbaijan to a position of a major military power in the South Caucasus. Diplomatically too, Baku has been successful in containing prospects of international recognition of the Nagorno-Karabakh region. Moreover, the country also managed to maintain, in many respects, exemplary relations with Russia amid numerous geopolitical disturbances which have occurred in the South Caucasus and wider Eurasia since early 2010.

Armenia, on the other hand, sandwiched between Turkey and Azerbaijan, and having a lifeline to Iran in the south and Georgia to the north, has been economically constrained, which limited its military potential. In many ways this led to Armenia’s excessive dependence on Russia.

Turkey’s entrance into the scene has also changed the traditional post-1994 balance of power around Nagorno-Karabakh. As the year of 2020 shows, its support for Azerbaijan is beyond mere rhetoric. Ankara is pursuing a clear geopolitical agenda of anchoring its influence at the Caspian Sea at the time when Azerbaijan has become a major gas supplier, even surpassing Russia’s position. It is no wonder that Turkey's Vice President Fuat Oktay recently announced that Ankara would not hesitate sending soldiers and providing military support for Azerbaijan in case such a request is made by the Azerbaijani government.

These trends underline Russia’s changing position in the South Caucasus. It can no longer pursue its traditional balance of power policy, but it should also be careful not to antagonize Azerbaijan – the process which could invite greater Turkish influence in the region, solidify the South Caucasus energy and transport corridor well beyond the Russian ability to intervene.

Thus Russia has to tread carefully. It would have to intervene at some point in the ongoing conflict and it is not so much because of Armenia and the growing disenchantment among the Armenian public with its northern ally, but mainly because in case of Azerbaijan’s total victory, Baku might be less pliable and could actually pursue a more robust independent foreign policy, much to Russia’s geopolitical detriment.

In a way, we could talk about a declining Russian influence in the South Caucasus. Ever since the Russians helped to stop the Armenia-Azerbaijan war in 1994, the Kremlin has been instrumental in maintaining an uneasy status quo. Cultivation of good relations with both sides has been a backbone of Moscow’s policy. Even when the balancing game did not work, as in 2016, it was still Moscow which compelled the two warring states to agree to a durable cease-fire after just 4 days of fighting.

This is unlikely to happen this time. After all, Russian diplomatic efforts to stop the fighting has so far failed twice. Now a certain initiative is with the US. The latter has been calling on Baku and Yerevan to stop fighting and use diplomatic channels. “The resolution of that conflict ought to be done through negotiation and peaceful discussions, not through armed conflict,” one of Pompeo’s statements read, “and certainly not with third party countries coming in to lend their firepower to what is already a powder keg of a situation.”

Those efforts have also failed as the recent statement of the Armenian PM, Nikol Pashinyan showed: “Everything that is diplomatically acceptable to the Armenian side ... is not acceptable to Azerbaijan anymore.” But the visit of foreign ministers of Azerbaijan and Armenia on October 23 to meet Pompeo marks a significant step in US diplomatic efforts to contain the fighting and then work on a durable ceasefire.

Thus the geopolitical equilibrium Russia has so meticulously worked on throughout the last 25 years has been upended both diplomatically and militarily. Azerbaijan now has a Turkish alternative which provides it with the necessary geopolitical maneuvering to limit Russian influence.

However, it is also plausible that an operation on such a grand scale could not have been carried out by the Azerbaijani side without the Kremlin knowing it or at least noticing it. Otherwise we are dealing here with a major collapse of intelligence-gathering on the Russian side.

Moreover, to portray Russia as a geopolitical loser in this unfolding situation would not be entirely correct. After all, Moscow possessed an array of tools for influencing the war and it could still benefit even with Azerbaijan winning. To keep Turkey at bay Moscow will have to allow Azerbaijan to get back some territories for its military success. It could limit Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev’s push to include Turkey in the negotiations process. Moscow might also hope that a victorious Baku would be grateful enough for Russia to use the opportunity to re-engage Azerbaijan in the talks for EEU and perhaps even CSTO membership.

The long-standing assumption that Armenia losing its control over Nagorno-Karabakh and the surrounding territories would disqualify the need for Russian alliance among Armenia political elite, might have to be reconsidered – Yerevan will still have little space for maneuvering out of the Russian geopolitical orbit. After all, the Azerbaijani success could also allow the Russian side to have its military footprint in the conflict zone itself through a major peacekeeping mission.

Emil Avdaliani, non-resident fellow at the Georgian think tank, Geocase, specializes on wider Eurasia with a particular focus on South Caucasus and Russia, relations with China and the US. He can be reached at emilavdaliani@yahoo.com.

See Also

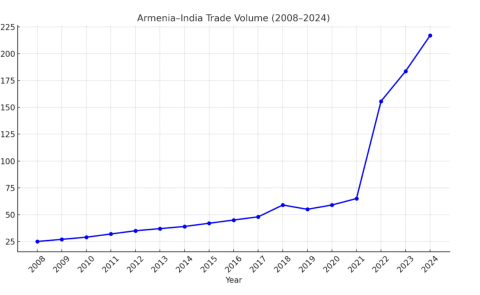

Armenia and India: Building New Bridges in Trade and Strategy

Between Tehran and Tel Aviv: Azerbaijan’s Neutrality Dilemma Amid Rising U.S.-Israel Tensions with Iran

From Neorealism to Neoliberalism: Armenia’s Strategic Pivot in Foreign Policy After the Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict

Georgia and Russia: New Turn in Bilateral Relations