Growing Geopolitical Divisions in the South Caucasus

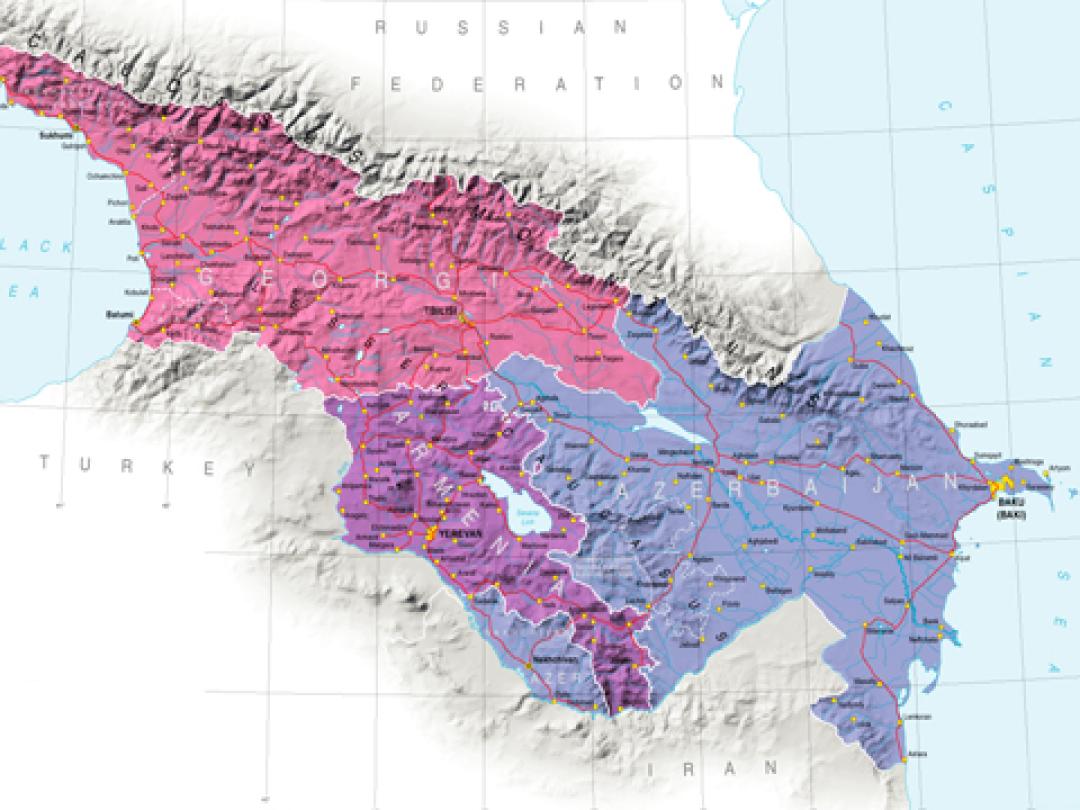

Critical changes are taking place in the geopolitics of the South Caucasus. The distancing of the West and a hit at the prospects of democratic development in Armenia are among some of the Second Karabakh War results. The conflict has also elevated the region to the level of primary concern for Russia and Turkey, and linked it to the geopolitics of the Middle East – a significant development which ushers in the age of great power competition in the South Caucasus.

The South Caucasus experiences geopolitical changes of a tectonic level. To be sure, the process was in work for quite some time, perhaps from the late 2000s. But the latest Karabakh War further underlined the trend and in turn set in motion other no less important developments in the geopolitics of the region.

The first trend is a decline of democratic ideals and concrete achievements made by the region's states. The Armenian democracy took another hit with the war results. The country will now be more than ever before dependent on the non-democratic Russia. If earlier, the Karabakh issue was one of those areas where Russia was not directly involved and much of policy-making towards the region depended on Yerevan and internal Armenian politicking in general, with Russian troops now stationed in the troubled region, the Kremlin influence on Yerevan will be expectedly bigger.

It is also the issue about the growing incompatibility between a fledgling democracy and a large non-democracy. Dependence on Russia brings extensive concessions. From a longer-term perspective, the new decade will be consumed with the Armenian leadership’s efforts to rebuild the army, economy and general morale among the population. This would require resources – military support from Russia, which possibly will involve backtracking in democratic values as Russia has been quite suspicious of Armenian PM Nikol Pashinyan’s reformist drive.

The trend also concerns Georgia. Though the Western support is crucial for the country, the spread of strong democratic ideals has been no less important for having a stable South Caucasus. With an expected backtracking in Armenian democratic traditions, Georgia’s conviction in its pro-Western political and economic course will only strengthen, though the conditions for achieving a meaningful democratic progress in the region will deteriorate.

More concretely the war effectively puts an end to Armenia's attempts for multi-vector foreign policy attempts. Gradual erosion of Armenia's multi-axial foreign policy efforts intensified following the 2016 four-day war with Azerbaijan. The growing asymmetry in Armenia-Russia alliance culminated in the 2020 war. From now on Armenia's dependence on Russia would be more pronounced with no viable geopolitical alternatives such as hopes for closer ties with Iran, Israel and even NATO and the EU. It was suggested that reliance on China could help keep afloat Armenia’s multi-vector foreign policy, but so far there is little Beijing could see in building closer ties with Yerevan particularly as these moves could complicate China-Russia relations. Perhaps beyond potentially larger economic contacts Armenia’s hopes in China are overstated.

Though Russia was dominant in the region since the early 19th century, the post-Soviet period marks a break in this trend when a gradual emergence of the collective West (mainly through influence in Georgia) and now of Turkey (through extensive military, economic and political support for Azerbaijan) turns the South Caucasus into an increasingly fractured region. The three states are now divided by larger regional powers. This also signals the dawn of great power competition where each external actor will pursue its own military agenda, infrastructure projects as well as economic activity.

The time when the South Caucasus was viewed as a monolithic entity/region is being replaced with openly competitive visions of larger players. Russia, Turkey and the collective West, should each devise a diversified foreign policy corresponding to the needs of the three states in the region.

The recent developments in the region also reflect a decline of Western involvement. Regional players, Russia and Turkey, plan to (re-)open trade routes which would increase the connectivity, but could also further sideline the collective West. And this concerns not only the actual infrastructure projects. The collective West’s limited presence is also seen in the way the Western peacemaking standards and conflict resolution methods are being trumped by Russian alternatives.

The sidelining of the West also concerns actual long-term political visions for the South Caucasus. Russia’s vision is versatile: mixture of economic measures to keep Armenia and Azerbaijan closer, partly through military moves such as physical presence on Armenian and Azerbaijani soil, partly through fostering one-to-one bilateral ties.

Turkey’s vision is similar plus the development of the regional infrastructure. Moreover, on the political level the recent suggestion on creating a six-nation pact involving the South Caucasus states plus Russia, Turkey and Iran, is yet another example of growing Western political regress from the region.

Since the end of the Soviet Union the South Caucasus has held a strategically important position in the calculus of regional powers. But the region has not been high on the agenda of regional powers’ foreign policy. It has served as a periphery to greater geopolitical games. Recent developments in the regional geopolitics, though, and most notably the Second Karabakh War results usher in a major tectonic change: the Caspian basin and the South Caucasus have become inextricably linked to the Middle East (ME). Two major players Russia and Turkey, which have increased their footprint in ME over the past decade, look at the South Caucasus as a part of a great geopolitical game from the Mediterranean to the Caspian region. Ankara and Moscow now make their strategic moves in the South Caucasus within the context of the developments in the ME. This portends more challenges to the South Caucasus, as the region could be subject to geopolitical trade-offs. But it also means that the space has been elevated in status – it now occupies a near primary geopolitical theater for Turkey, Russia and the West.

Emil Avdaliani (@emilavdaliani) is a professor at European University (Tbilisi, Georgia)

See Also

From Neorealism to Neoliberalism: Armenia’s Strategic Pivot in Foreign Policy After the Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict

Georgia and Russia: New Turn in Bilateral Relations

3+3 Initiative as a New Order in the South Caucasus

Economic Cooperation Between Armenia and Georgia: Potential and Challenges Ahead