Occupied Lives: Georgians’ Daily Struggles Under Russian Control in Gali

Nina (her name was changed for security reasons) often crosses the small bridge that connects the Russian-occupied region of Abkhazia with the Georgian-controlled part of the country. Her identity was concealed out of security concerns, as the de facto government in occupied Abkhazia, which is supported by Russia, could pose difficulties for her. “Every sunny day, I try to walk on this bridge because I truly believe that if I dream there, my dreams will come true,” she says. All her dreams are related to Abkhazia, her homeland. Yet, at this stage, she must accept a harsh reality. The reality is that her homeland is under Russian occupation. Every time she travels to a Georgian-controlled area for different reasons, she needs to go through three checkpoints to get back home.

“Firstly, I must pass through a Georgian checkpoint. After that, there is an Abkhazian checkpoint and, finally, a Russian checkpoint. Everything starts when you pass through the Georgian police”, she says. “If a policeman on the Abkhazian side is drunk, he might offend you. They will inspect your bags and everything else. You cannot even carry a Coca-Cola bottle bearing Georgian writing”. Upon closer inspection, Nina and other ethnic Georgians will not have an issue if they carry just one small bag. A problem arises when there are more bags, especially large ones.“Once, one of my friends bought a kitchen appliance and was asked to pay 50 GEL ($20) in order to take it home. But she was lucky because only one man was there. You should also give money to everyone else who comes. This happens only to ethnic Georgians in Abkhazia”, she says.

A bloody war that raged in the region for 14 months dates back to 1992 and marks one of Russia's first interventions in Georgia’s domestic affairs following the collapse of the Soviet Union. The military clashes between Russians, Russia-backed Abkhazians, and Georgian forces ended in 1993, when Sokhumi, the administrative center of Abkhazia, fell, resulting in approximately 250,000 Georgians being forced to flee the breakaway region.

Nina’s homeland, Gali, where about 96% of the population was Georgian before the war, is the only district in Abkhazia where the de facto authorities have allowed the return of displaced ethnic Georgians. While various reports suggest that between 40 000 and 60 000 Georgians chose to return to Gali, the total number of local residents is unknown.

What daily life in Gali is like, the rest of Georgia only knows from the ethnic Georgians who reside there. There is no right for others to cross the occupation line. And they say life there is bleak and fragile. Abkhazia's de facto administration imposes institutional restrictions, depriving them of basic civil and political rights. Local residents say they struggle on a daily basis and feel neglected by the local de facto government.

“The population of Gali leads an active economic life and pays significant taxes, but it is clear from the local infrastructure that they receive little support from the de facto leadership of Abkhazia", says Tamta Mikeladze, Social Justice Center Equality Policy Program Director. Last year, the organization published a report on the problems facing local residents in Gali. "There was a particularly harrowing episode when the garbage infrastructure was moved from Sokhumi to Gali, and a large amount of garbage is being transported to this district, near residential areas", says Mikeladze. Tamta describes the move by the de facto government as a symptom of marginality.

Garbage infrastructure is not the only issue in Gali that concerns local residents. Drinking water there is mostly unavailable. People obtain drinking water from natural sources or purchase it from stores, as water quality is typically subpar. On occasion, when repair work is underway, the population can be without water for several days or weeks. During the winter, electricity is supplied to Abkhazia on a set schedule every day. Additionally, the Gali district is not gasified; the gas is only available in balloons, which can only be filled in the city. “Daily life here is very challenging. But we got used to it and now consider it normal", Nina says. “When you have a headache in the evening and need medication, you won't find a pharmacy in most places. It is necessary to travel to the city of Gali, and even there, 24-hour service is not available.”

Only the Central Hospital of Gali can provide emergency medical care, but the equipment there is outdated. When patients are in critical condition, they need to be transferred to Georgian-controlled territory but this is quite complicated. The checkpoints are closed between 20:00 p.m. and 08:00 a.m.. Normally, it’s impossible to cross the occupation line during this period of time. Documents are another issue. In the absence of Abkhazian documentation, it is also difficult to transfer the patient to Georgian-controlled territories. "In difficult situations, you must have someone who can intervene and resolve the problem. Personal contacts are extremely critical here", Nina says.In order to cross the occupation line and get to Georgian-controlled regions, locals need a residence card or an Abkhazian passport. Abkhazian legislation allows dual citizenship only with the Russian Federation. Since Gali residents hold Georgian citizenship, they cannot obtain Abkhazian citizenship or a passport. When it comes to a residence permit, the cost of getting this document is high, and many cannot afford it.

According to data from 2021, 20,224 people in Gali district have a residence permit. The de facto Abkhazian regime does not accept Georgian ID cards or passports, which are what the majority of Gali residents use. “Getting documents for one person costs around 250-300 GEL ($95- $115) and takes months. When there are 7-8 members in the family, their income will not be sufficient to obtain the documents. Hence, each year, a different family member handles the paperwork, and the documents have never been settled in the family”, Nina tells us.

Since many don't have the required documents, they can't travel to Georgian-controlled territory to buy some vital items or receive medical care, which they can't obtain in the occupied part of the country. In these cases, locals usually bypass checkpoints by taking alternative routes that are considered to be extremely dangerous. During the trip, they must cross the river in dangerous conditions or walk through uncharted forests for 7-8 hours. Over the years, a few people have lost their lives crossing the occupation line illegally.

Tako is another ethnic Georgian born and raised in occupied Gali. Her name was also changed for security reasons. The de facto government usually summons locals for interrogation if they read their critical interviews. According to Tako, local residents are so oppressed and downtrodden that they cannot even express their concerns. "Since they are convinced that there won't be changes, they don't ask for any," Tako says. Tako's family member is a teacher, and her salary amounts to 350 GEL ($135). “Because she is Georgian, she faces injustice at every step. If she asks for a pay raise, they will tell her to quit”, Tako tells us.

The situation deteriorated significantly following Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Control over Georgians has increased, and eavesdropping has become more common. Supporting Ukraine is categorically unacceptable to the local de facto regime. Tako tells us that a few families she knew quite well were forced to flee the region only because they supported Ukraine on social media. “It happened right after the Ukraine war started. They gave some time for people to leave the region. Nobody expresses their opinion. It is a very tense situation here. People are frightened. Whenever the de facto government doesn't like something, they'll interrogate not only you but also your family, friends, and anyone you know”, Tako says.

While facing myriad problems under Russian occupation, residents of the Gali district also feel abandoned by the Georgian government. Since the Georgian side doesn’t have control over the occupied territory, they are powerless to change anything. Attempts to include the daily problems of the Gali population in various political agendas, however, are weak, Tamta Mikeladze argues.“Georgia does not have a format that is focused on the transformation of conflict. In addition to big political issues, there should be an opportunity to discuss daily problems faced by Gali's residents,” Mikeladze says. “Currently, we only have the Geneva International Discussions (GID) to address the impacts of the 2008 war. There is the Incident Prevention and Response Mechanism (IPRM) too, however, the meetings on the Abkhaz direction were suspended in 2012”.

The current circumstances make life in Gali for ethnic Georgians extremely challenging. Consequently, an increasing number of youths are escaping the occupied region. They claim they have no future in Gali. However, everyone in Georgia realizes how crucial it is that Georgians remain and live in the occupied part of the country.“The presence of Georgians in Gali has the potential to transform conflicts. Unless this occurs, the alienation between Georgians and Abkhazians will only increase,” Mikeladze says.

Contributed by Khatia Shamanauri, a freelance journalist from Georgia.

See Also

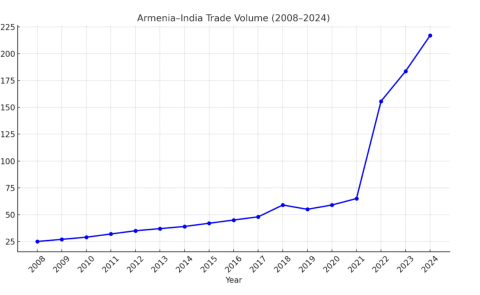

Armenia and India: Building New Bridges in Trade and Strategy

Between Tehran and Tel Aviv: Azerbaijan’s Neutrality Dilemma Amid Rising U.S.-Israel Tensions with Iran

From Neorealism to Neoliberalism: Armenia’s Strategic Pivot in Foreign Policy After the Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict

Georgia and Russia: New Turn in Bilateral Relations