Ambassador Rahimpour: Iran’s Caucasus Policy Is “Above Pezeshkian”

Iran’s newly elected president may be unable to redefine national security policy in the Caucasus, but this does not accommodate changing circumstances. Since the outbreak of the war in Ukraine, Iran's role in the Caucasus has gained new significance. Iran has historically opposed Russian expansionism and Turkish ambitions in the region. However, the country is now one of the “big three” powers in an informal forum initially created to facilitate consultation for the future of Syria: Iran, Russia, and Turkey. This plurinational forum is now setting the security agenda in the Caucasus. While these three powers have profoundly different worldviews and different relations with the “plus three” countries of the South Caucasus – Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan – they have a consensus over a “better between us” regional approach. The region is being framed in the region.

Tehran has been seeking to capitalise on opportunities to escape economic sanctions, creating a new economic status quo with Russia. Working in a three-plus-three framework, Tehran strives to attract investment and make the most of a regional surge in transit trade. However, there are also challenges that Iran has to address. Presenting itself as a quintessential status quo power, the question is: what is Tehran’s position vis-à-vis the Armenia-Azerbaijan conflict? Could Iran maintain close trade and security ties with Russia while curbing its Near Abroad aspirations? Whether tighter economic ties with Turkey and Azerbaijan can be squared with reservations over a Turkic economic community? The way Iran balances its priorities is unclear, particularly in the context of a broader security crisis in the Levant.

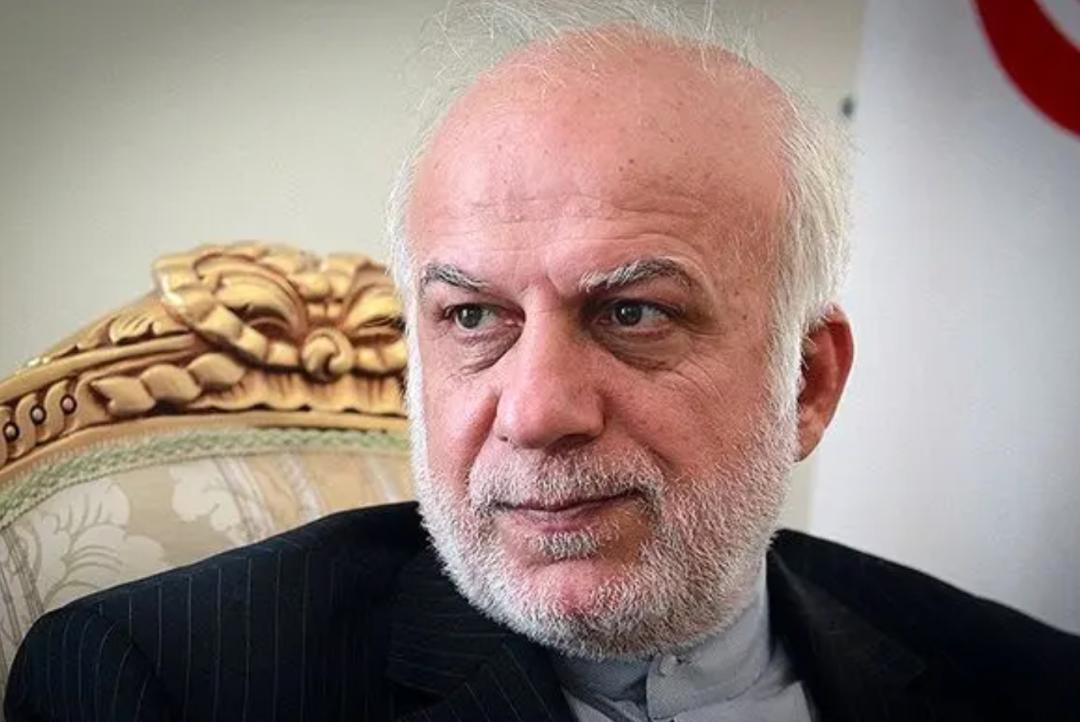

Trying to understand Iran’s positioning in the region, Caucasus Watch talks to Ambassador Ebrahim Rahimpour, who served as former Deputy Foreign Minister and Special Representative for the Caspian Sea during the tenure of Foreign Minister Javad Zarif (2013-2021).

Where does the Caucasus feature on Iranian priorities today?

The Caucasus is essential for us historically and politically. After the USSR fell, emerging successor states significantly redefined the new Iranian neighbourhood. As always, Tehran pursued a constructive path. More recently, we had the two wars between Armenia and Azerbaijan over Karabakh that have transformed the territorial status quo. The Ukrainian war is transforming both the region as a whole and, of course, reframes the overall framework in which this conflict evolves.

The importance of the Caucasus for Europe is that it takes place on the sidelines of the Ukrainian war, which public opinion obviously prioritises. If Europe does not affirm the red line that international borders must remain unchallenged here, they cannot establish this principle there. This is in line with the Iranian position, as Tehran cannot accept any revision of the territorial status quo anywhere, including, naturally, our neighbourhood.

In June, Azerbaijan and Iran held joint military exercises in Nakhichevan. There was speculation of a subsequent joint exercise in Karabakh. What are the common security threats for the two countries? What was the purpose of common “counter-terrorism” training? What message did these exercises convey to Yerevan?

To answer your question, we are aware of the role of Russia, Turkey, and, to some extent, Israel in the Karabakh conflict. We are less clear of the European position on these matters. That is an open question for Iranian diplomats: “Where does Europe stand?”

In the past, we have affirmed our own red lines, conducting military drills along the border of both our Caucasian neighbours. That was meant to communicate our position on the inviolability of borders to both Baku and Moscow.

The recent exercise you are referring to was not of strategic significance. This was Tehran exhibiting a will for normalisation andde-escalation of tension. A common terrorist threat does not exist, although we fear the threat of Israel from Azerbaijani soil.

Let me go back to the military drills of Iran’s Revolutionary Guards along the Armenian border in 2022, to which you alluded. At the time, the message that dominated headlines was that Tehran would not tolerate the seizure of Armenian territory along Syunik. The same message was communicated by placing an Iranian Consular General in Kapan. Iranian defence ministers have been participating in informal troika meetings with India and Armenia, which is thought to provide military logistics guarantees for landlocked Armenia. There were unconfirmed suggestions of an agreement on military procurement between Yerevan and Tehran. My question is whether Iran acts as a security guarantor for Armenia?

Regarding the troika between Armenia, India, and Iran, I would say that this is not an established diplomatic framework. Clearly, Armenia is trying to counterbalance Azerbaijan. Pakistan is backing Azerbaijan and India is siding with Armenia, playing out an old enmity by proxy in the Caucasus.

Regarding the role of Iran as a security provider, this is not our official foreign policy line, and we are trying to maintain a neutral position. According to the official Iranian position, we are on the side of peace and stability. We want to exclude not only Israel from the region, but also Turkey. We are trying to limit Russia’s influence in the region, as Tehran has also historically suffered from Moscow’s expansionism.

Following the surge of tension in the Levant (Gaza, Lebanon), the question arises as to whether the perceived presence of Israeli assets in the region could lead to crisis contagion in the Caucasus. How likely is that scenario? According to open sources, President Pezeshkian is looking for a resolute approach to operations against Israeli assets in the region.

The spread of the conflict from the Levant to the Caucasus is not very likely. Israeli actions against Iran were provocative but not on a large scale. Iran has directly and precisely communicated its concerns to Baku, which are now very clear. President Aliyev appears to have received the message that allowing or enabling Israel to act from its territory would have unwanted consequences.

President Pezeshkian’s position vis-à-vis Azerbaijan is essential, but final decisions on national security policy in the region are made at a level above the Presidency. Since the President is from the Azerbaijan region and speaks the language, we are hoping he can contribute to a prosperous relationship.

Tehran hopes to commercially link the Caspian Sea to the Black Sea after investing in port infrastructure in southern Russia. Given the Caspian Sea's evaporation and the overuse of water in the Volga, there are implications for Iranian national security and social cohesion. Do you see any geopolitical consequences stemming from the climatic challenge?

The Caspian Sea has great potential for multilateral cooperation but it remains unfulfilled. The Ukrainian War has adversely affected the situation. The convention of the Caspian Sea suggests that no one can enter the region other than littoral states. Instead, we see that the notion of the “Zangezur Corridor” introduces an outside player in the region and is, in this respect, a negative vision.

As regards the Iranian investment in Southern Russian ports, Iran is quite satisfied with the ability to navigate the Volga and the economic benefits of transit trade via the Caspian Sea. Our return on investment is satisfactory. We are also looking forward to the development of the International North-South Corridor from Chabahar to Europe. The Ukrainian war disrupted the full development of this project, but we are making steady progress.

We have concerns about evaporation, but I think that is a global issue. We care about the environment as much as any of the littoral states and the rest of the world, perhaps more. This corridor has allowed us to lift some of the pressure from international sanctions. Unfortunately, Iran has not been able to take full advantage of its transit position to maximise trade traffic in the region. I don’t believe that the scale of the environmental crisis is as pronounced as your question implies. Although I do not have a full scientific grasp of events, I am unsure of an imminent crisis.

The Iranian Navy recently conducted drills in the Caspian Sea near Astara. What is the perception of the threat to Iran in the region?

These manoeuvres are not strategically significant. It is a message of deterrence to everyone rather than someone specifically. The message is that we are ready for every eventuality, and we monitor reactions to our capability deployment. The Iranian Navy shows its presence, but our neighbours should not make too much of this.

Azerbaijan just applied for BRICS membership. Iran has joined and signed a special agreement with the Eurasian Customs Union. Given the parallel expansion of the two non-western frameworks, do you see a radical departure in Iranian foreign policy in the Caucasus? Is the 3+3 framework a “better between us” forum, or is there scope for greater alignment of regional economic interests in a multilateral framework?

Azerbaijan’s addition to BRICS is more of a political than an economic gesture and is designed to please Russia. In our case, Russia and Iran are sanctioned countries. Sanctions are de facto consolidating our countries into an economic bloc, with India and China benefiting more than the West. The West is undermining its own economic influence in the region through the sanctions regime. The 3+3 framework is a solid forum, but there is much work to be done. At this moment, it is unclear whether this forum can evolve into an entity.

Interview conducted by Ilya Roubanis

See Also

Giorgi Tumasyan: Tbilisi and Yerevan Can Jointly Tackle Geopolitical Challenges

Marina Ohanjanyan: The EU Still Matters in TRIPP

Victor Kipiani: Windows, Not Walls - Georgia’s Way Ahead

Dr Rehman: Beijing’s Quiet Hand in Pakistan–Armenia Thaw