Another War in Europe Looms

About author: Svenja Petersen is a political economist who graduated from SciencesPo Paris, the Free Univeristy of Berlin, The London School of Economics and The College of Europe in Natolin. She currently works in the field of international development cooperation and is a freelance political analyst for several media outlets.

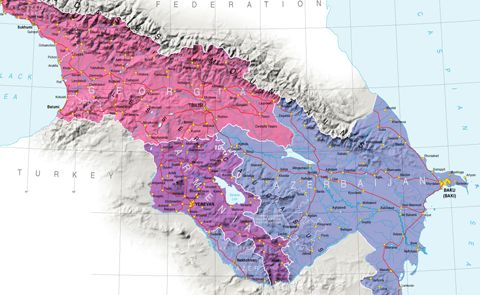

For more than 60 days now, the blockade of the Lachin Corridor connecting Nagorno-Karabakh with Armenia has been ongoing, and the situation is becoming more threatening with each passing day. An escalation seems more and more inevitable.

More than two months ago, on December 12, 2022, Azerbaijani environmental activists, who are reportedly linked to the government, blocked the Lachin Corridor. According to the activists, they are protesting against the illegal mineral mining in Nagorno-Karabakh through the local de facto authorities.

The Lachin Corridor is both the lifeline and the “Achilles heel” of Nagorno-Karabakh, as it is its only link to the outside world. The vulnerability of the corridor, which is just 5 kilometers wide, has been evident since December 12, 2022, when the blockade of the Lachin Corridor, and thus Nagorno-Karabakh, resulted in an ever-increasing humanitarian crisis in the region.

Whether the Azerbaijani eco-activists are truly independent and acting on their own is largely subject to scrutiny. Various sources claim that some of the protesters belong to Azerbaijani state structures or are affiliated with the Azerbaijani government. Some have even claimed that some of the protestors are Azerbaijani soldiers.

Upon the request of the U.S. Secretary of State, Antony Blinken, to lift the blockade, Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev informed him that there is no such blockade. The Armenian Prime Minister, Nikol Pashinyan, in turn, stated that it was clearly about "breaking the will of the Armenians of Nagorno-Karabakh to live in their homeland (...), expecting the Armenians of Nagorno-Karabakh to leave their homes en masse."

The humanitarian situation in Nagorno-Karabakh is worsening with each passing day. In some cases, according to Armenian sources, Azerbaijan temporarily cut off electricity and gas to the region. The Internet also repeatedly went down. The situation is increasingly deadlocked as neither side deviates from its position. The de facto authorities of Nagorno-Karabakh insist on full independence from Azerbaijan, while Armenia seems to be far from the idea of providing military support to Stepanakert. This increases the potential for escalation by Azerbaijan.

Exactly how the situation will develop is difficult to predict at the moment. But in the meantime, it is becoming increasingly clear that there will probably be a further escalation. A commentary by Rusif Huseynov, an Azerbaijani political scientist and head of the Baku-based Topchubashov Center, has been quoted as such by the Austrian newspaper Der Standard: "The people of Azerbaijan recognize the outcome of the war in 2020 as a success, but also think that the result is incomplete. That a part of our country is not subject to our jurisdiction." Such a comment from one of Azerbaijan's most respected think tanks can be considered quite directional. At a time when Azerbaijan is putting a noose around a territory of the Nagorno-Karabakh, such a comment is a clear indication that Azerbaijan will also tighten this noose. At the same time, it can be considered a confession that Azerbaijan will not accept the 2020 trilateral statement in the long run and that it still lays claim to the remnants of Armenian-controlled Nagorno-Karabakh. And it can also be regarded as a confession that the self-declared environmental activists, who, by the way, conspicuously often wear fur coats, are no coincidence in these times.

For a long time, the blockade was seen as Azerbaijan's bargaining chip against Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan. The aim of this Azerbaijani pressure was probably to force Nagorno-Karabakh to be vacated and handed over to Azerbaijan. Yet, Nagorno-Karabakh does not seem to be the only target of Azerbaijan’s policy. Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev has repeatedly demanded that Armenia release a corridor that would run across Armenia’s internationally recognized state territory. This so-called Zangezur corridor would connect Azerbaijan's heartland with its exclave Nakhichevan, and from there, would continue to run into Azerbaijan’s “brother state”, Turkey. This corridor would provide a direct transport route between Azerbaijan and its exclave, thus boosting trade and reducing costs for Azerbaijan. At the same time, it would further Turkey's pan-Turkic ambitions by establishing direct transport and trade routes through the South Caucasus and on to Central Asia.

Yet, Pashinyan made no concessions to Azerbaijan. He presumably hoped for international support from abroad, but this failed to materialize apart from a few verbal condemnations by European and American politicians. No real pressure is being put on Azerbaijan to end the blockade, neither through economic nor diplomatic sanctions. On the contrary, the EU is now buying more natural gas from Azerbaijan than ever before to replace Russian imports. Hence, Pashinyan's strategy of sitting out the blockade for the sake of international help did not work.

Now it appears that Aliyev is losing patience. There are three possible scenarios for how Azerbaijan might proceed in the future to try to conquer all of Nagorno-Karabakh.

The first scenario is that Azerbaijan will continue to maintain its siege until it becomes almost unbearable for the locals to live there. At such a moment, Azerbaijan could open the Lachin Corridor in the direction of Armenia, expecting the largest possible number of Armenians to leave the territory on their own out of fear, hunger, and pressure. Then the territory would be left empty for Azerbaijan to take. Despite stating that there is no blockade of Nagorno-Karabakh, a demand by Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev in January 2023 pointed to exactly such a scenario. He called on the Armenians of Karabakh to either take up Azerbaijani citizenship or leave Nagorno-Karabakh. Interestingly, he said they could also leave the country "with the peacekeepers," which may indicate that the Russian peacekeepers are no longer welcome in Azerbaijan either.

The second scenario could be that Azerbaijan sticks to its siege quasi-permanently. Thus, Azerbaijan could cause a humanitarian catastrophe to which a large number of people will succumb. Subsequently, Azerbaijan could seize the territory. This scenario points out the importance of the time factor. The longer the blockade lasts and the longer Azerbaijan does not face any consequences, the more threatening the situation of the people in Nagorno-Karabakh becomes. However, this scenario is also relatively risky for Azerbaijan because nobody knows how long the people in Nagorno-Karabakh will withstand the blockade and whether they will be able to survive relatively self-sufficiently - especially in the approaching spring. There is also talk of establishing an air bridge between Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh, for example by opening Stepanakert airport, but this option doesn’t seem real due to the fact that the territory of Nagorno-Karabakh is internationally recognized as part of Azerbaijan. Over time, the pressure on Azerbaijan to lift the blockade could also increase. Therefore, this scenario is less likely, because sooner or later Azerbaijan will try to act and create facts on the ground before the signs could change again.

Following the second scenario, Azerbaijan could launch a major military offensive on Nagorno-Karabakh in a third scenario. This is a very likely outcome because Azerbaijan has repeatedly tried to conquer Nagorno-Karabakh militarily through war, and its much better equipped army now controls the most important strategic heights in the region. Due to the omission of food, medicine, and arms supplies to Nagorno-Karabakh, this point in time seems ideal from an Azerbaijani point of view.

Which of these scenarios will come to pass also depends on Russia, which is in fact supposed to secure the Lachin Corridor as a supposed peacekeeping force. Nevertheless, the Russian forces tolerate the blockade by Azerbaijan. The question remains, however, whether and when Russia would intervene.

Russia's role in this situation remains unclear. There are claims that Russia, which is considered to be Armenia's protector, will only step in on Armenia's behalf if Armenia makes concessions to Russia that will strengthen Russia's position in the post-Soviet space. Such a concession could be Armenia's accession to the Belarusian-Russian Union State. The head of the Armenian Security Council, Armen Grigoryan, publicly indicated that Moscow is making such a demand. However, this was later denied by both the Kremlin and the Armenian Prime Minister.

Other claims suggest that recently Azerbaijan has become a much more attractive partner than Armenia for Russia since Russia can resell its natural gas through Azerbaijan, thereby circumventing Western sanctions. This could then mean that Moscow will give Azerbaijan a free hand in Nagorno-Karabakh because the Kremlin expects more profits from cooperation with Baku than with Yerevan.

However, it can also be assumed that Russia cannot and does not want to get involved in the conflict any further, since its military and human attrition in the Ukraine war is already too high. From this perspective, a new war in Nagorno-Karabakh seems almost unavoidable. Yet, it is a ticking time bomb.

See Also

From Neorealism to Neoliberalism: Armenia’s Strategic Pivot in Foreign Policy After the Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict

Georgia and Russia: New Turn in Bilateral Relations

3+3 Initiative as a New Order in the South Caucasus

Economic Cooperation Between Armenia and Georgia: Potential and Challenges Ahead