From the Black Sea to Central Asia: Corridor Crystallization

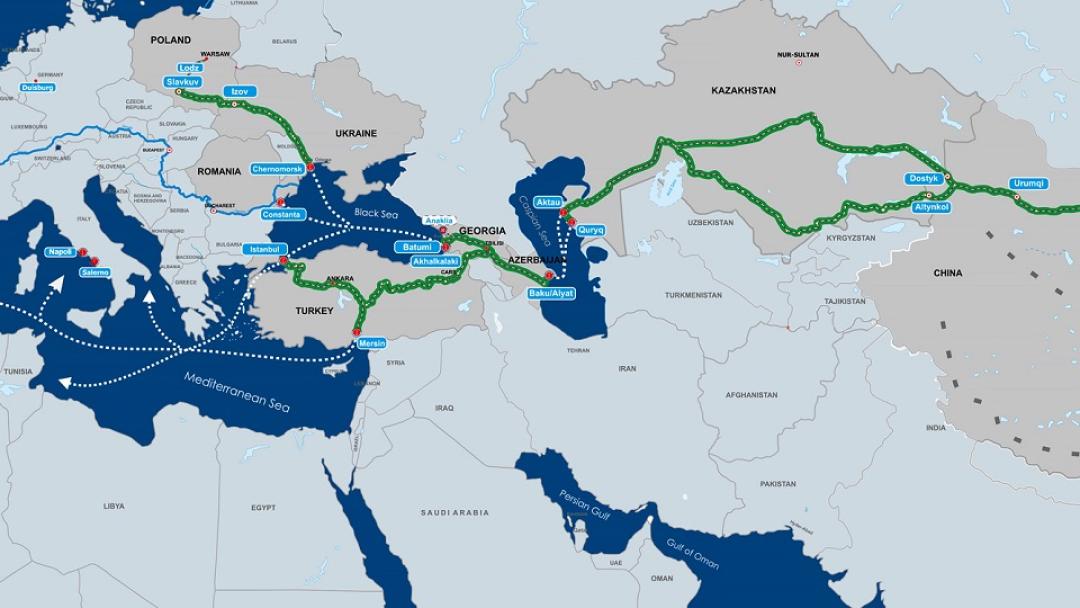

Recent events, ranging from Azerbaijan’s new partnership agreement with China to the progress on the China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan railway highlight major shifts in Eurasian connectivity.

In July, Azerbaijan and China signed a strategic partnership. The document is an upgrade from previous types of cooperation and revolves around the issues of sovereignty and bilateral support in the international arena. But more importantly, the agreement also mentions the pledge toward expanding the work on the Middle Corridor.

Both states have traditionally enjoyed close ties, but those were limited in scope because China was less interested in the South Caucasus in general. Azerbaijan’s increasing shift toward Asia with the interest in BRICS and SCO further contributed to closer ties between Baku and Beijing. For the latter, Azerbaijan now plays an important role along the Middle Corridor.

The strategic partnership agreement, however, is not an isolated development. For example, in early June, China, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan reached a long-awaited agreement on finally starting the construction of the railway project (abbreviated as CKU), which would connect the three countries.

China pledged to provide financial support for half of the project – nearly $2,35 billion in low interest. Bishkek and Tashkent too pledged to provide $573 million each. They will also form a joint holding company, with a Chinese company owning 51 percent. Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan, along with their respective holding companies, will equally divide the rest.

The construction is expected to begin in late 2024, and this time it seems there is more interest in the project implementation than in previous years. For decades, the initiative remained only on paper or in public pronouncements due to a lack of financing and an unstable political situation in Kyrgyzstan, a country that has witnessed a series of revolutions in the past two decades. Furthermore, the question of which parts of the two Central Asian countries the railway would pass also posed significant challenges. Last but not least, Russia appeared to be against the project, as Moscow has historically been more interested in building north-south connectivity than east-west routes.

Favorable geopolitical conditions created a wider momentum for the decision. Russia’s ongoing invasion of Ukraine pushed the countries of Central Asia, the EU, and increasingly China to seek and test trade routes that would bypass a traditional one going through Russia. Moscow, too, has grown less resistant to the project, partly due to its inability to stop it but mostly because of its growing dependence on China, which has worsened since the invasion of Ukraine began.

Yet the major problem remains the funding, as the railway’s total cost presently stands at around $4,7, and the existing financing pledges by Central Asian states and China indicate that more than $1 billion still remains outstanding.

Geographically further westward, in May, the Georgian government awarded the right to construct the deep seaport of Anaklia to a consortium of several Chinese companies. Located on the Black Sea’s eastern shore, Anaklia is poised to play a major role in the expanding Middle Corridor.

The decision is a major victory for the Chinese side, as previous attempts to win the bid ended in failure in 2015 when an American consortium pledged to build the port. The failure occurred partly due to Georgia's internal political issues, and partly because the Chinese side was less interested in trading through the port, preferring the Russian corridor. It also follows the signing of a strategic partnership agreement between Georgia and China in July 2023, which highlighted the need for work on the Middle Corridor.

Seen from a geographic perspective, there is now a clear line stretching the Black Sea to China-Central Asia borders, coalescing into a major corridor to connect to the EU market. The South Caucasus and Central Asia represent the shortest overland route to do so, and the opportunity is quickly grasped by Beijing.

Where does the collective West stand on this shifting connectivity in Eurasia? In January, the EU and international institutions pledged to invest $11,8 billion into the development of the Middle Corridor. The sum is divided into supporting the existing infrastructure projects as well as financing new ones in Central Asia and the Caspian Sea ports. Brussels clearly recognizes the potential of the corridor, with cargo traffic reaching 2,8 million tons by the end of 2023, nearly twice as high as in 2022. The EU’s financial involvement aims at helping the corridor reach a figure of 11 million tons of cargo shipments annually by 2030.

Yet the EU has room to do more, especially given its much-touted Global Gateway initiative, which aims at spending around $300 billion on infrastructure to compete with the Chinese Belt and Road Initiative. Moreover, Brussels’ major ally, the U.S., though supportive of the Middle Corridor, has done little to invest in the South Caucasus and Central Asia. One tiny exception is the visit by U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) Kathleen Tai in mid-June to Central Asia, where the sides discussed support for the Trans-Caspian connectivity.

Both also experience shaky periods in relations with their key partner in the South Caucasus, Georgia, which serves as a bridge to Central Asia through Azerbaijan. The Georgian government's adoption of the "agents law" has significantly strained ties, leading Washington and Brussels to downgrade their strategic cooperation with Tbilisi.

Taken all together, winning the competition in the Middle East requires finances and a clearer geopolitical vision. Resources to build the corridor matter most, and in this aspect, Beijing is quicker.

Emil Avdaliani is a professor of international relations at European University in Tbilisi, Georgia, and a scholar of silk roads.

See Also

NATO and the South Caucasus: Lack of Vision or Strategic Withdrawal?

Georgia in 2026: Between Great-Power Fault Lines and Internal Fractures

U.S.–Armenian Relations Amid Shifting Power Dynamics: Expectations and Challenges

Ukraine War’s Spillover in the North Caucasus