Georgia and the Daunting Task of connecting Asia and the EU

As the war in Ukraine began and a number of traditional Eurasian trade routes became untenable, Georgia has been active diplomatically in advancing the Middle Corridor and its place in it.

The connectivity patterns throughout the Eurasian region are changing as a result of the war in Ukraine. The Russian route, which for decades served as a crucial link between the EU and China, is closed, and Beijing fears that economic sanctions imposed by the West on Russia could potentially have a severe spillover impact on the Chinese economy.

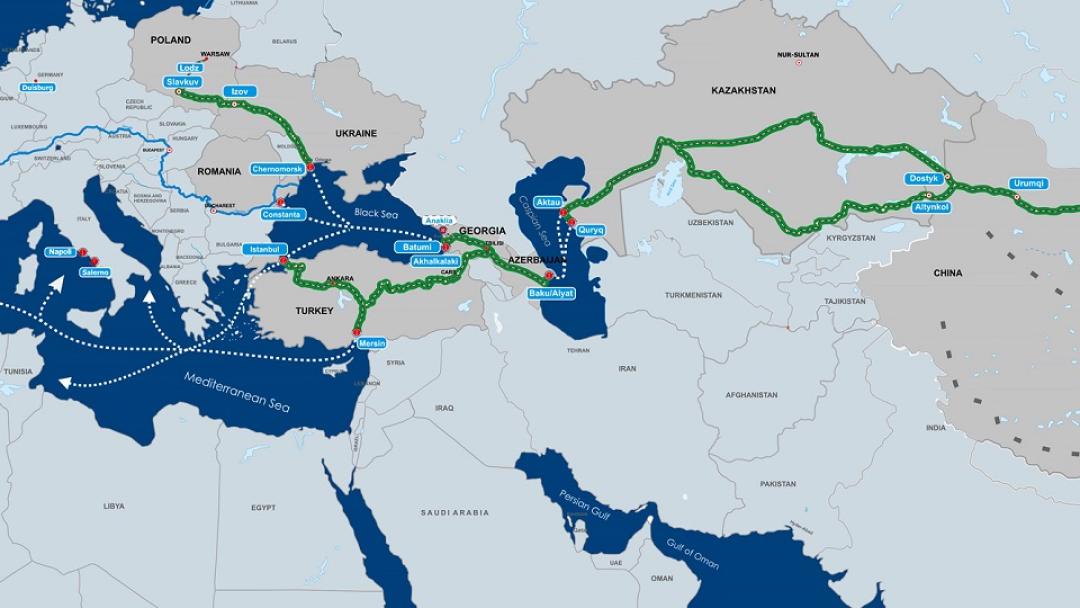

This major geopolitical shift pushed the Central Asian states, Turkey, the EU, and China to seek alternative corridors. The Middle Corridor, which goes from the Black Sea to Central Asia via the South Caucasus, geographically, is the shortest route between western China and the EU. Georgia plays an important role in this regard, owing to its existing infrastructure and geographic location.

Georgia has taken part in a number of intergovernmental meetings which are aimed at boosting the corridor. For instance, the development of the Trans-Caspian International Transport Corridor was the subject of a quadrilateral statement by Georgia, Azerbaijan, Turkey, and Kazakhstan on March 31, which produced a joint statement on the need to strengthen the corridor. In May, together with Kazakhstan and Turkey, Georgia discussed the Middle Corridor in a meeting held in Ankara. Later that month, the Georgian railway company announced that it was collaborating with companies from Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan to establish a new shipping route between the Georgian port of Poti and the Romanian port of Constanta.

Apart from this, the Georgian leadership has been active through a series of visits to Central Asian states. Georgian PM Irakli Garibashvili also paid a visit, arriving in Uzbekistan on July 18 to meet with his Uzbek counterpart. In a meeting with Uzbek PM Abdulla Aripov, Garibashvili discussed bilateral cooperation with a focus on economic relations and Georgia’s role as a transport corridor for Uzbekistan.

On July 20th, the Georgian state delegation visited Turkmenistan, where both states signed an agreement on launching direct flights connecting the countries and increasing cargo turnover between them.

Another country visited by the Georgian delegation was Kazakhstan, where on July 26–27, President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev and the Georgian PM discussed opportunities for bilateral cooperation in trade and logistics, with a focus on the Middle Corridor.

The significance of trade corridors and Georgia's role in them is evident. Tbilisi has been insistent on playing a major role in Eurasian connectivity and made this ambition the backbone of its geopolitical aspirations ever since the end of the Soviet Union. With the war in Ukraine, the prospects for such objectives seem more promising.

The necessary infrastructure is already in place. The 2017 launch of the Baku-Tbilisi-Kars railway and the expanding network of regional roads connecting the Caspian Sea to the Black Sea provide a solid foundation for trade cooperation between China and the EU in the South Caucasus. Both Azerbaijan and Georgia are BRI signatories and have extensive trading ties with China.

Drawbacks to Georgia’s Ambitions

Yet the Middle Corridor is a vulnerable concept. Geography is a significant obstacle since the route is effectively multi-modal and includes both land and the sea. This complicates the shipment. No wonder that China has always favored shipping commodities via the Russian route since it included fewer states and a geopolitical environment that was more or less predictable and stable. The situation is different in Central Asia and more so in the South Caucasus. It is true that relations between Georgia and Russia appear to be stable, though with deep mutual suspicions, while Azerbaijan and Turkey seem closer to peace with Armenia. However, it is still unclear how the conflict in Ukraine will affect the Caucasus. If Russia prevails, it will probably be less patient with a wide corridor circumventing it from the south through Georgia.

Additionally, the Black Sea lacks infrastructure, where having a deep sea port is now more important than ever. There is still no clear resolution to the Anaklia saga. In an ideal scenario, it would take years for the port to be built. Another issue is that getting to the EU from Georgian ports is challenging due to the poor condition of the rail infrastructure in Romania and, as of late, Ukraine. Thus, the South Caucasus route before the Ukraine War was never sufficiently competitive.

From a broader perspective, the Middle Corridor also lacks effective inter-governmental dialogue. Those measures, which we mentioned above and which involve Georgia, Azerbaijan, and Kazakhstan, are a good indicator of where the process might potentially go. But it could also stall where it stands at the moment, as it has often happened in previous years and decades. To have tangible progress, either the EU or China should be heavily investing in the corridor to create a relatively seamless transit via the seas and lands of several countries.

So far, China has shown little economic interest in the South Caucasus. From the Beijing’s perspective, the region remains not only under Russia’s geopolitical purview but also under the Kremlin’s heavy economic influence. The intrusion from China might not be welcomed by the Kremlin. However, as other cases (such as in Central Asia) have demonstrated, China can go against Russian interests when and where it is critical for Beijing. China is also weakly represented in Azerbaijan’s economy. The latter is firmly within Turkey’s and Russia’s economic areas, which limits the space for Beijing. Moreover, with the war in Ukraine, China’s presence in the Black Sea region is also undergoing significant changes. It has not been big enough even before the invasion, with Beijing failing to get the right to build the Anaklia port and facing resistance from the West in its attempt to win over Ukraine.

Emil Avdaliani is a professor at European University and the Director of Middle East Studies at the Georgian think-tank, Geocase.

See Also

From Neorealism to Neoliberalism: Armenia’s Strategic Pivot in Foreign Policy After the Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict

Georgia and Russia: New Turn in Bilateral Relations

3+3 Initiative as a New Order in the South Caucasus

Economic Cooperation Between Armenia and Georgia: Potential and Challenges Ahead