Middle Corridor Gets a New Boost with Tentative Progress on Trans-Caspian Connectivity

A new round of efforts to build the Trans-Caspian pipeline might not produce concrete results, but new developments on the ground show that Turkmenistan and other countries lying along the route are increasingly cooperative about the potential project.

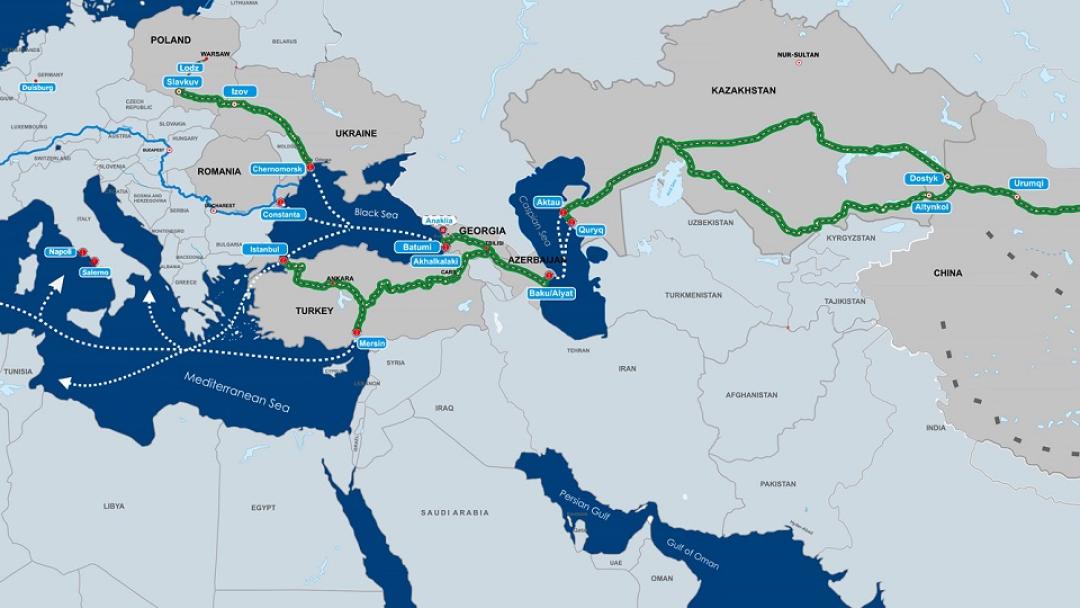

There is yet another flurry of diplomatic and political efforts to help realize a much-touted Trans-Caspian pipeline project, which potentially would go from Turkmenistan to Azerbaijan. The idea is to export the Central Asian gas to the European Union via the South Caucasus in circumvention of the Russian mainland.

This is not a new idea and it has not worked so far because of the geopolitical complexities surrounding the project. Moscow and Tehran are not pleased with having the Turkmen gas in Europe, as it would essentially rule out the need for Russian and Iranian energy resources in the rich European Union.

The war in Ukraine has changed the dynamics in Eurasia, with the European dependency on Russian gas and oil diminishing and Brussels actively seeking alternative sources. Azerbaijan is one of such options, and the two sides duly signed an agreement to this end in 2023 on doubling gas imports to the EU from the Caspian country by the end of this decade. Yet, most recent reports indicate that Azerbaijan might not be able to fully meet the agreed upon EU energy demands, which push both Baku and Brussels to consider Turkmenistan’s help.

This could explain Turkmenistan’s recent diplomatic engagement with the South Caucasus, EU countries, and Turkey. For example, a delegation from Turkmenistan visited Bucharest in mid-July to discuss regional cooperation. This was followed by the announcement that the Central Asian country would sign an agreement with Georgia, Azerbaijan, and Romania on establishing an energy corridor from Central Asia to the EU.

In August, Rashid Meredov, the Turkmen minister of foreign affairs, met with his Turkish counterpart in Ankara to talk about advancing trade and commercial ties. The two parties decided to work together to raise bilateral trade to the $5 billion target. This followed the March agreements, which aimed at enhancing bilateral cooperation in the gas industry and preparing the basis for exporting Turkmen gas to Europe. Parallel to this, in May, Turkish Energy and Natural Resources Minister Alparslan Bayraktar met his Azerbaijani colleagues to reach a natural gas agreement and commit to facilitating the export of Turkmen gas via the South Caucasus.

For Turkmenistan it is not only about the fact of potentially sending gas to the EU, but also successfully positioning itself along the Middle Corridor, which has been expanding over the past 2,5 years since the beginning of the war in Ukraine and the structural shifts in Eurasian connectivity. Given China’s growing efforts to advance the Middle Corridor via the construction of the Anaklia port in Georgia and the progress on the China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan railway, Ashgabat is aiming not to miss the chance of becoming a part of new arrangements.

These developments turn a new page in the saga of efforts on potential construction of the Trans-Caspian pipeline or increase in coast-to-coast trade. Countries on both sides of the sea basically agree on where things stand, but structural challenges remain and are unlikely to disappear in the coming future.

Building a major pipeline in the Caspian Sea is primarily driven by geopolitics rather than financial constraints or geographic distance. Without the backing of at least one greater power (for instance, China or Russia), this would be difficult to accomplish. Turkey is another big actor, but Ankara will still need support from other players. Overall, since Moscow is hesitant to assist Turkmenistan in becoming its primary rival in gas deliveries to Europe, its position on the trans-Caspian project will continue to be the main obstacle.

Therefore, when comparing what is more realistic for Turkmenistan, it is clear that positioning itself as a transit country within various new connectivity projects in Eurasia is far more realistic than hoping for a positive end to the trans-Caspian pipeline project. Due to its size and geographic location, Turkmenistan is now increasingly attractive to Russia. For instance, Moscow has recently upped its diplomatic game around upgrading the eastern branch of the International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC), which runs to Iran and further to India via Turkmenistan.

Ashgabat has also increased its efforts to build transborder infrastructure with the Taliban government in Afghanistan. Given India’s own ambitions to build links to Central Asia via Iran and its Chabahar port, Turkmenistan is set to garner a larger role as a transit space. Moreover, other Central Asian states like Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan are also seeking to broaden their connections with the outside world. Obviously, one of the directions is toward Iran and India, and here too, Turkmenistan could benefit. For isntance, in April, Ashgabat reached a deal with Astana and Kabul on setting up favorable tariff conditions for transit trade between China and Afghanistan via Central Asia. If operational, the trade corridor could help reduce transportation costs and time by 10-12 days.

Emil Avdaliani is a professor of international relations at European University in Tbilisi, Georgia, and a scholar of silk roads.

See Also

NATO and the South Caucasus: Lack of Vision or Strategic Withdrawal?

Georgia in 2026: Between Great-Power Fault Lines and Internal Fractures

U.S.–Armenian Relations Amid Shifting Power Dynamics: Expectations and Challenges

Ukraine War’s Spillover in the North Caucasus