Russia and the South Caucasus after the Fall of Nagorno-Karabakh

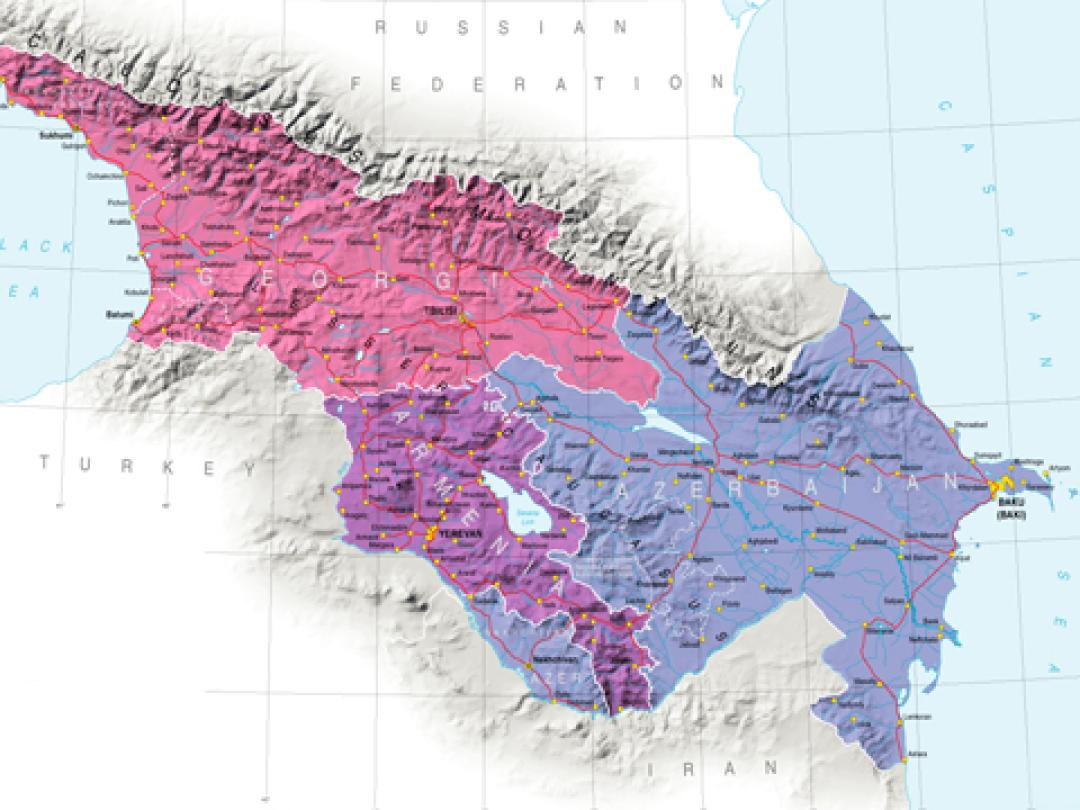

With the end of the Nagorno-Karabakh entity and possibly a bloody series of wars between Armenia and Azerbaijan, Russia’s foreign policy toward the South Caucasus is undergoing fundamental shifts.

The fall of the Nagorno-Karabakh enclave signifies a pivotal moment in Russia's diplomacy with the South Caucasus. This shift is primarily highlighted by strained relations with its historical ally, Armenia, which did not receive anticipated support from Moscow during a series of confrontations with Azerbaijan since 2020. The tensions have been evident through a series of formal protests handed over to the Russian ambassador in Armenia, criticism of the Russian government, and the inefficacy of Moscow-led multilateral institutions such as the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO).

Russia has traditionally maintained an equilibrium between Armenia and Azerbaijan. Now, there seems to be a discernible tilt in Moscow’s position towards Azerbaijan, influenced in part by Yerevan's rigid stance on peace talks around Nagorno-Karabakh and partly by Putin's reservations about the Armenian leadership. Additionally, geopolitics played its role: following the Ukrainian conflict, Azerbaijan became a principal land conduit to Iran, aiming to pivot Russia's foreign trade from west to east.

Although Russia may adapt its foreign policy in response to these power dynamics, this new era might not be entirely favorable for Moscow, suggesting its diminished power in the South Caucasus. This waning influence, heightened by the Kremlin’s distracting war effort in Ukraine, could be viewed as a clear sign of the gradual diminution of Russian geopolitical clout in the region spanning from the Black Sea to the borders of Central Asia and China.

In the South Caucasus, Russia is now facing a dense geopolitical environment, contending against the likes of the US, EU, Turkey, Iran, and, more recently, China. This complex dynamic offers Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia more diplomatic flexibility. They can now joggle one actor against another, increasing the momentum behind the now-fashinable multi-vectoral foreign policy. Highlighting these shifting dynamics, France recently agreed to enhance Armenia's defense capabilities by signing military agreements, while Azerbaijan and Iran consented to a new railway bypassing Armenia's southernmost region of Syunik. These are just a few of the numerous other examples signaling a shift from Russia-West competition toward more multi-aligned dynamics in the South Caucasus.

Aware of constraints on its influence, Russia began using a different set of strategies toward the South Caucasus. Recognizing the historical influence of Iran and Turkey in the region, Russia began openly supporting the 3+3 format, which consists of three South Caucasus states and three big surrounding powers. The recent summit held in Tehran on October 23 manifested Russia’s desire to pursue this novel approach.

From Moscow’s perspective, the 3+3 initiative is a logical continuation of past initiatives. Over the past thirty years, several initiatives have been proposed to boost regional cooperation in the South Caucasus, such as the "Peaceful Caucasus Initiative" and the "United Caucasus." The 3+3 concept originated after the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War in 2020. However, this format has its sceptics, with countries like Georgia and Armenia harboring reservations due to internal tensions among member nations.

Nonetheless, post-the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, Armenia might see the potential benefit of participating, particularly given its growing ties with Iran, which aims to curb Azerbaijan's regional aspirations and counterbalance Turkish influence.

Many people in the West and in Georgia view the 3+3 initiative as yet another attempt by the South Caucasus' three dominant regional powers—Iran, Russia, and Turkey—to expand their influence. Iran and Russia both support "regionalism" in the South Caucasus, putting emphasis on the idea that neighboring nations should be primarily responsible for addressing regional challenges. Moreover, this sentiment was echoed in various statements made by Baku, who seems increasingly frustrated by the Western mediation efforts and is more reliant on the Moscow-led negotiating track.

However, there are even differences among the major powers. While Russia appears supportive, in the longer run it remains wary of the 3+3 initiative, fearing it could amplify Turkey's influence and elevate Iran's position in Armenia and the wider South Caucasus. Grounds for discomfort are indeed there. Iran has taken advantage of Russia's vulnerability as a result of the conflict in Ukraine, while Russia is gradually but steadily depending on the Islamic Republic for trade, transit, and the opportunity to get around Western sanctions.

The problem for Moscow is that, at the present moment, it cannot deny these two Middle East powers from enjoying greater influence in the region. What many in the West miss is that Moscow feels far more comfortable with Ankara and Tehran than with the West. Iran and Turkey are competing within acceptable boundaries, while the West, from the Kremlin’s point of view, has crossed all red lines.

For Russia, the only real chance to maintain its influence in the South Caucasus is through engaging the actors in the Middle East and denying the non-regional powers any tangible presence in the region. Indeed, the Tehran meeting reiterates the intent of Turkey, Iran, and Russia to minimize Western influence in the region. To counter this, the EU and US should be more assertive in delineating their regional aspirations for the South Caucasus. Potential steps could include offering Georgia the coveted EU candidate status, reinforcing its pro-Western diplomatic posture, and positioning the EU to influence the broader South Caucasus. Building closer ties with Armenia could be another measure, especially given the state of bilateral relations between Yerevan and Moscow.

Emil Avdaliani is a professor at European University and the Director of Middle East Studies at the Georgian think-tank, Geocase.

See Also

From Neorealism to Neoliberalism: Armenia’s Strategic Pivot in Foreign Policy After the Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict

Georgia and Russia: New Turn in Bilateral Relations

3+3 Initiative as a New Order in the South Caucasus

Economic Cooperation Between Armenia and Georgia: Potential and Challenges Ahead