The Lost Garden: Karabakh Armenians One Year After Exodus from the Region

Thousands of Karabakh Armenians have spread to the provinces of Armenia due to the expensive rental of apartments in Yerevan, the capital city of Armenia. Families want to be as close to the capital as possible in order to have a decent school, kindergarten, or job. Many of them, unable to handle the social-psychological challenges, have permanently departed from Armenia. According to Armenia’s National Security Service data, as of April 1, 9.100 Karabakh Armenians left Armenia forever.

One-story village houses from the 1960s are located along the 7th street in Masis city, Ararat Province, Armenia, which is 14 km from Yerevan. Displaced families from Nagorno-Karabakh live here mostly on a rental basis. As one walks by, a foul stench emanates from the turquoise water channel that flows through this area. A mosquito swarm is flying above the dirty waters. The secondary school sits on one side of the channel, flanked by houses and cattle sheds where the locals keep their cows. Children ski on the construction sand, speaking in the Karabakh dialect. A garbage truck honks, signaling the residents to take out their trash. The town in front of me is called Masis.

Armen Beglaryan, who is bedridden, lives in one of such houses in Masis. He was born in Grozny, Chechnya. During the first Karabakh war in the early 90s, he moved to his native city of Martakert {Aghdara} in Nagorno-Karabakh. "I was playing on the walls of a shelled building when I fell from the wall with a heavy brick; after that, my pains began. I didn't pay attention; I even started practicing karate, but as the years passed, I felt pain in my muscles and bones, till the doctors diagnosed me with Bekhterev disease. It's my fault, why didn't I live a quiet life like other children? Why was I such an "active" boy?" Armen accuses himself.

"I can't sit or stand; my father took care of me. Somehow, I protect myself from mosquito attacks at night. I somehow moved with the help of the ceiling rope. As my dad grew older, Alzheimer's symptoms began to manifest in him. He fell one day in the bathroom, and days later he passed away from the foot pain here in Armenia. He was 86 years old, but he still took care of me. Currently, a woman from Karabakh, who lives next door, is caring for me. I need serious medical help, but what they offer here in the hospital is just to wear an adult diaper; even for consultation with a doctor, I have to pay. Many people ask, "Is this the life you live?" But what can I do? I am also human; I also want to live; death is always there; you talk about living. Everything is a consequence of war.

I do not believe that Armenians can return to Nagorno-Karabakh. If it was possible, why did people leave their homes? I don't believe that it will be possible at least in the next ten years. Just yesterday, they {Azerbaijanis} were killing Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh. Is there a guarantee that the same will not happen upon our return? We have no other option; we are currently living in Armenia. Because I moved to Armenia prior to the recent wars in 2020 and 2023, the Armenian government does not view me as a refugee. I am considered an Armenian citizen; therefore, I do not benefit from any social support,” Armen says.

There are several explanations why Karabakh Armenians are opposed to embracing Armenian citizenship. Firstly, many could not take with them the necessary documents they required in Armenia while leaving Nagorno-Karabakh in September 2023. Parents' birth, marriage certificates, etc. Making a mistake while writing someone's name can lead to immediate bureaucratic difficulties. Secondly, those families who already have a son who is almost 18 years old, and if they accept Armenian citizenship, their son must undergo mandatory military service in Armenia. "We ran away from the war, army, again?" That's what they think. The majority of them deliberately do not want to accept Armenian citizenship; they say we have the same blue passport as all citizens of Armenia. What is the problem? They hope that something will change for the better someday. A very small part is forced to accept Armenian citizenship in order to be able to take advantage of the housing program announced by the government, but they are uncertain about their ability to return a portion of the money they have received to the bank.

It is noteworthy that if the parents in the family accept Armenian citizenship, their children automatically become Armenian citizens as well. “As of August 30th, we received more than 4.300 citizenship applications from people forcibly displaced from Nagorno-Karabakh.” Armen Ghazaryan, the Head of the Migration Service of Armenia, announced in the National Assembly on Tuesday that about 3.000 people have already received Armenian citizenship.

At the same time, Armenians born in Armenia face similar difficulties as Karabakh Armenians do Vahik was born in Yerevan, then moved to Nagorno-Karabakh and worked as a dentist there for 15 years. He took a passport with code 070 there, but he cannot understand his status in Masis, Armenia.

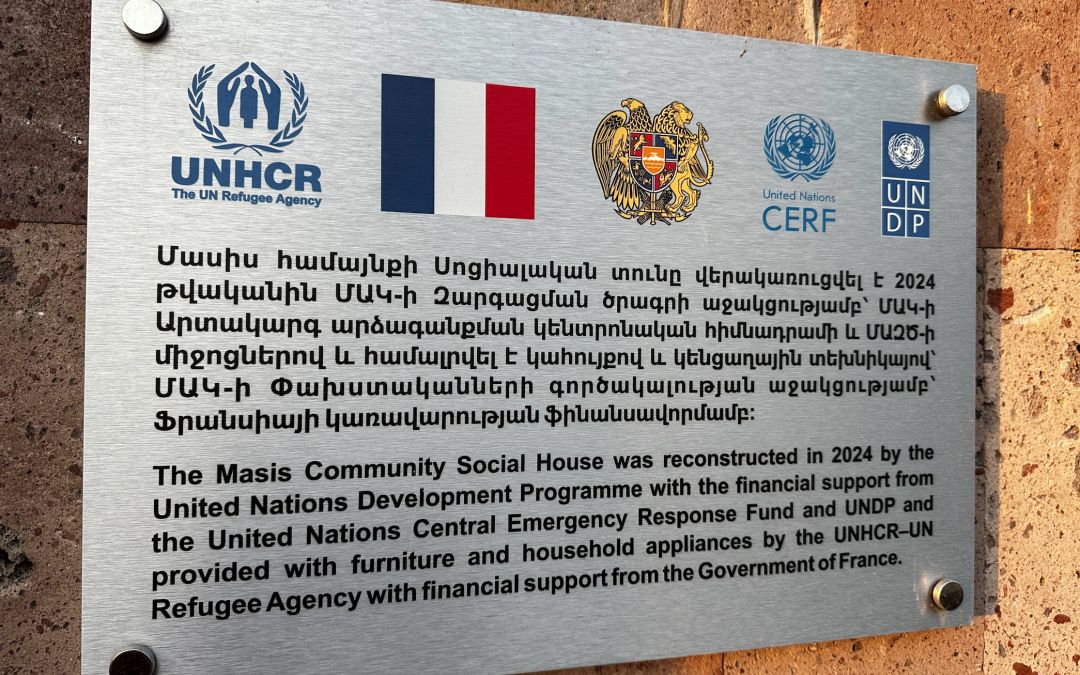

“I had a stroke, and because of this disease, I was given accommodation in this building, which was renovated by the United Nations with the financial support of the French government. Before that, we lived with Karabakh Armenians in a dilapidated kindergarten building. My wife is a Georgian citizen; she is not allowed to live with me. Municipality says the room is for one person. Isn’t it funny? I tried to find a job; I was offered a position as a builder, but how can I do hard work with this disease? People think I'm drunk when I walk. I consulted a doctor, and the neurologist said, can you slowly put your index finger up your nose? I did. That was the medical "help" I received in Armenia. I can't solve my passport problem, nor my status. I don’t benefit from any government social welfare payments. You know, we even pay for drinking water here because running water is dangerous to drink,” says Vahik.

Ten other displaced families from Nagorno-Karabakh live with Vahik, who have a disabled family member. They say they are grateful to the United Nations and the French government for the asylum. Anyway, they wish to return to their homes. “Unlike many Karabakh Armenians, at least we live in good conditions, but all I need is my home, my four walls, my yard, and my garden in Khnushinak {Khanoba} village (Martuni {Khojavand} Region of Nagorno-Karabakh),” says Ira Aghajanyan, who lives in the same building as Vahik.

“I feel broken here; I don't feel anything here in Armenia, as if my senses are not working. There was this rose bush in our yard in Karabakh, and if you passed by it, the sharp smell could easily make you feel drunk. There is no taste in Armenia; there is no joy in my heart. I have a memory of every stone in my house. I used to admire the beauty of attractive girls when I sat for two minutes in the park of Stepanakert {Khankendi}; I was breathing there, when I sat here in Masis Park, I didn't feel any energy. That's how we live here, like strangers. I don't know where to go when my deceased relatives' birthdays approach. Their graves remained in Nagorno-Karabakh. I don't want to go to church here; I'm angry with God. I promised myself that I would only go to church in Karabakh. Was Karabakh “Sodom and Gomorrah?” Wasn't there a single righteous man for God to keep us there? It is true; I am afraid of God, but even I have lost faith in Him.” Ira complains to God and adds that it is possible to return to Karabakh in case of real security guarantees, but not like those provided by Russians.

“Many naive Karabakh Armenians greeted Russia with "spasibo" when the so-called peacekeepers arrived in Nagorno-Karabakh. I remember back in the Soviet years, when the Russian soldiers were still in Nagorno-Karabakh. I remember what they did: a special permit was required to leave the house after 12:00 at night. At that time, we threw out the Russians from Nagorno-Karabakh; now they brought them back and imposed “peace” on us. We did not ask Russia for help; it was the fault of Armenian politicians, but as a result, we, ordinary people, suffered,” says Ira, blaming the Armenian authorities.

“I have only shown kindness to Azerbaijanis in my life; I am not a politician; what is my fault in reaching this day? In any case, I am willing to live in Nagorno-Karabakh, as long as there is a guarantee of safety and no murders. When the authorities of Nagorno-Karabakh met with Azerbaijanis in Barda, I hoped that they would achieve an agreement. I didn't want to leave my house, but it was almost impossible. One is chanting conjugation while the other is carrying a curse. As a result, we have neither one nor the other. 33 years ago, one group was chanting a miatsum (reunion with Armenia), while the other one was chanting for independence. As a result, we have neither one nor the other. I want to return to Karabakh, but it doesn't seem very realistic at the moment,” she says.

Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan also considered the return of Karabakh Armenians unrealistic. “I want to tell you about an episode that happened a few months ago. I was visiting Vayk, when a forcibly displaced woman from Nagorno-Karabakh approached me and asked, tell me honestly, how realistic is the matter of our return? I gave her the same response, that I can’t lie; I don’t find it realistic with the perception that some representatives of Nagorno-Karabakh are trying to represent the matter. Pashinyan stated in a press conference on August 31 that these individuals signed the dissolution order and promptly departed from Nagorno-Karabakh.

At the same press conference, he also said that he did not sign the document to dissolve Nagorno-Karabakh, but rather the authorities there. Additionally, Pashinyan pointed the finger at Samvel Shahramanyan, the newly elected president of Nagorno-Karabakh, on September 9, 2023, saying, "I'm not the one who signed the order on dissolving Nagorno-Karabakh."

In response, Shahramanyan called Pashinyan's statement a manipulation. “We see that this issue is being manipulated on various occasions in connection with the dissolution of Artsakh {Nagorno-Karabakh}. First, it is a false thesis, and that document, which we had to sign, made it possible to ensure the safe transfer of the civilian population to Armenia. I also want to inform you that the Armed Forces have moved from the minister to the last soldier. Unfortunately, we also had live hostages in the form of our military-political leadership,” Shahramanyan said.

Following the September 2023 war in Nagorno-Karabakh, the authorities of Armenia and NK have been regularly making accusations against each other when discussing this issue. As Mrs. Ira points out, this has resulted in significant hardship for ordinary people.

About author: Marut Vanyan is a freelance journalist from Nagorno-Karabakh, currently based in Masis, Armenia.

Photo credits: Marut Vanyan

See Also

NATO and the South Caucasus: Lack of Vision or Strategic Withdrawal?

Georgia in 2026: Between Great-Power Fault Lines and Internal Fractures

U.S.–Armenian Relations Amid Shifting Power Dynamics: Expectations and Challenges

Ukraine War’s Spillover in the North Caucasus