The South Caucasus and the Growing Alignment between Iran and Russia

Relations between Russia and Iran entered a new age. With heightened competition against the collective West, Tehran and Moscow see the need for enhanced bilateral relations, the effects of which could be felt in the region between them, namely the South Caucasus.

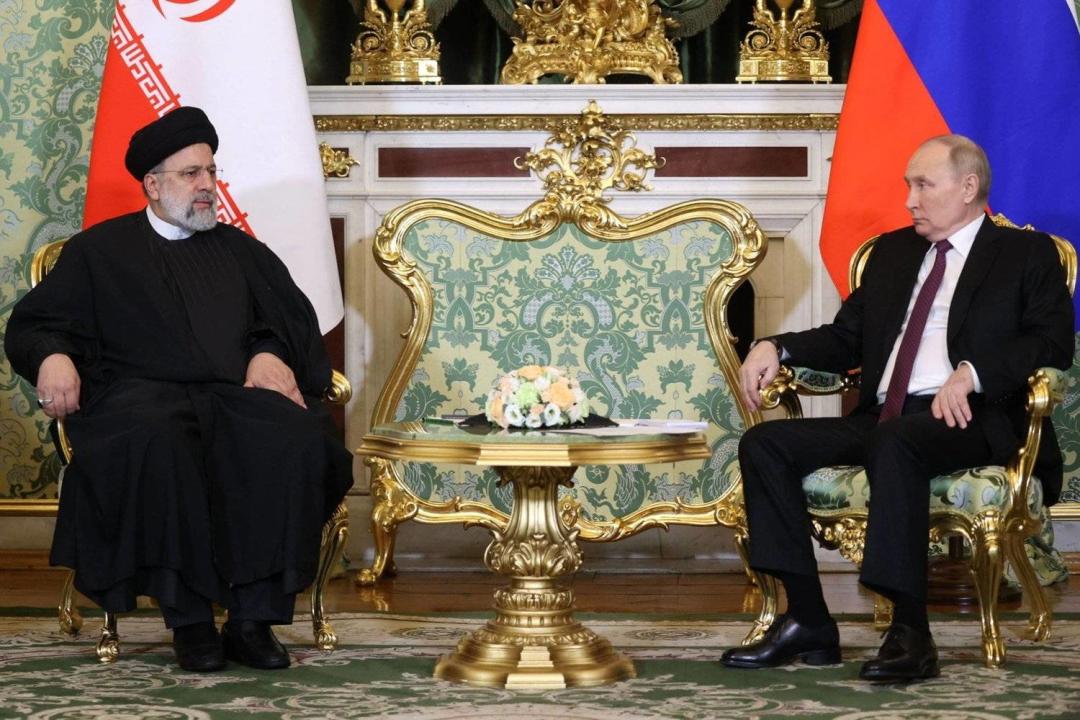

In early December, the Iranian delegation headed by the country’s president, Ebrahim Raisi, visited Moscow to discuss a series of important topics with Russian officials, including the situation in Gaza. Iran was keen to secure Russia's support on the global stage, especially as it perceived a growing rift in the Russia-Israel relationship and hoped to further deepen this divide.

But perhaps the most important issue was that Iran and Russia are presently on the brink of finalizing a comprehensive agreement to enhance their cooperation. It is unclear what this agreement would look like, but it will perhaps involve cooperation across most areas, such as the military, economy, and diplomacy.

This marks a significant turning point in their ties, reminiscent of the late 16th century, when Muscovy and Safavid Iran united against the Ottoman Empire. Despite a long-standing distrust among Iranians towards Russia, the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 and Russia's role as an arms and nuclear technology supplier to Iran have shifted perceptions. The dynamic accelerated following the war in Ukraine, when sanctions against Russia by the West began re-orienting its trade and investment relations away from Europe to Asia.

In this regard, Russia finds Iran a viable partner. Both nations, isolated by Western powers, find commonality in opposing Western dominance and in their need to bypass sanctions. Iran, recognizing Russia's reliance on Eurasian allies due to its problems in Ukraine, is now in a position of strength, pressing for the realization of long-delayed projects. The growing military and cyber cooperation between the two countries is notable, as are their expanding trade relations and efforts to develop the International North-South Transit Corridor (INSTC). This corridor, aimed to be operational by 2025, is gaining traction and promises to enhance connectivity between the Persian Gulf, the Indian Ocean, and Russian ports on the Caspian and Baltic Seas. During talks in Moscow, Raisi indeed highlighted the importance of INSTC. The discussions also reportedly led to an agreement on Iran's acquisition of Russian SU-35 fighter jets, advanced Mi-28 attack helicopters, and training aircraft for pilots.

The evolving Iran-Russia relationship reflects a shift in their approach to the global order, moving towards a radical, militarized vision against the US-led system. This aligns with their concepts of spheres of influence and regionalism, as seen in the South Caucasus and the Caspian Sea. Despite their convergence, Iran and Russia do not seek a formal alliance, valuing flexibility in the emerging multipolar world. Iran's foreign policy includes diversifying its relationships, as evidenced by its recent rapprochement with Saudi Arabia, its dealings with Russia, and even occasional clandestine attempts to talk with the EU or the US.

Russia and Iran share a geo-strategic alignment, largely due to their heavy sanctions by Western nations and their efforts to enhance their global influence. Both countries strive to reduce the West's impact on shaping the world order and the power projection of Eurasian nations. This common ground is driving their expanding cooperation, especially in the field of trade and investments.

2022 saw a 20% increase in Russia-Iran trade turnover, reaching $4.9 billion, up from $4 billion in 2021. This upward trend is expected to continue, with Russian officials anticipating a potential surge to $40 billion. Since 2019, an interim free trade agreement (FTA) between Iran and the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) has been in effect, recently extended until 2025 or until a permanent agreement is established, which was expected to be signed by late 2023.

Indeed, Raisi likely discussed this subject during his visit to Moscow. After the summit, the Iranian media reported that on December 25th both countries would seal an official agreement in that regard. If implemented, the deal would increase Armenia's role in Iran, as it would constitute the only physical border with the EAEU member states that the Islamic Republicwould have. Closer cooperation with Armenia would also fit into Iran’s overall ambition to support its small neighbor because of the pressure from Azerbaijan and the shifted balance of power in the region in favor of Baku.

Russian exports to Iran primarily include metals, food, agricultural materials, equipment, vehicles, and chemical products. Iranian imports feature food, agricultural materials, pharmaceuticals, textiles, footwear, and machinery. Following high-level talks, the countries agreed to conduct trade primarily in rubles and rials, with around 80% of transactions in national currencies. There's also a potential for a joint stablecoin, a gold-backed cryptocurrency, as an alternative to the US dollar in global trade.

In 2022, Russia was Iran's largest foreign investor, with $2.76 billion invested in oil projects. The largest joint venture is the Bushehr nuclear power plant. Significant Russian investment is also planned for the Sirik thermal power plant and Iran's oil and gas industry. However, Iran has expressed concerns over the slow pace of promised Russian investments.

The developing alignment between Iran and Russia, similar to Moscow's growing ties with Beijing, signifies a long-term shift in global dynamics. The ongoing war in Ukraine, the intensifying US-China rivalry, and China's increasing influence in the Middle East will likely cement Tehran-Moscow cooperation in the foreseeable future. The regions between them will be impacted the most. For the South Caucasus, it means that Tehran and Moscow will be more cooperative in preventing non-regional actors from playing an active role in the region.

Emil Avdaliani is a professor of international relations at European University in Tbilisi, Georgia, and a scholar of silk roads.

See Also

NATO and the South Caucasus: Lack of Vision or Strategic Withdrawal?

Georgia in 2026: Between Great-Power Fault Lines and Internal Fractures

U.S.–Armenian Relations Amid Shifting Power Dynamics: Expectations and Challenges

Ukraine War’s Spillover in the North Caucasus