Beyond the Deadlock: Armenia Revolutionises its Foreign Policy

Timing is propitious for bold moves in Armenia’s foreign policy. The opposition inside the country is weakened, while the momentum to sign an overarching peace agreement with Azerbaijan is growing. Similar developments also push Yerevan toward a rapprochement with Turkey potentially leading to overturning of South Caucasus geopolitics.

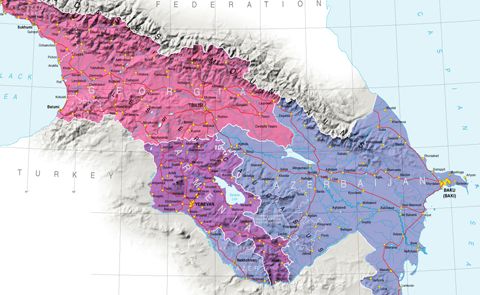

While all the attention is on Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the South Caucasus is experiencing long term geopolitical changes. I have already written about the impact of the invasion on the region and how each country is approaching the dilemma of balancing between Russia and Ukraine, but at the same time balancing the West and Russia.

But perhaps a more critical change in the region is the emerging rapprochement between Armenia and Azerbaijan. The Second Nagorno-Karabakh war of 2020 has irreversibly tilted the geopolitical balance in Baku’s favour. Armenia, which though managed to retain influence over the truncated Nagorno-Karabakh, has gone through a difficult realisation of the need to end its historic geopolitical isolation by improving relations with Turkey and Azerbaijan.

But this would require signing a definitive peace agreement with Azerbaijan, which would involve a major border demarcation effort, possible restoration of railway connections, and most of all recognition of each other’s territorial integrity. The latter point has been a particularly sore point in Armenian-Azerbaijani historically antagonistic relations. Yerevan has so far refused to recognise its eastern neighbour’s sovereignty over Nagorno-Karabakh.

This however could change as over the past several months the Armenian leadership has been quite positive about the potential peace agreement with Baku and recognising the troubled Nagorno-Karabakh as a part of Azerbaijan. At least Yerevan has not officially denied it would be following this path. It is likely that Armenia will be demanding autonomy for the Armenian population. Though impossible to say with certainty how the negotiations would unfold, a range of cultural rights guaranteeing the use of Armenian language is nevertheless likely to be ensured.

The discussion on the peace deal is built on months of previous positive moves in bilateral relations. On April 6th heads of Armenia and Azerbaijan held face-to-face talks in Brussels. Charles Michel said later that the parties agreed to “move rapidly toward a peace agreement” and set up a Joint Border Commission for border delimitation between the two sides. April 11th saw the first direct phone call took place between Armenia and Azerbaijan since 1990s. The countries’ FMs discussed the preparation on Joint Border Commission.

The anticipation for the agreement has been building. And the situation inside the country reflects tensions on the foreign policy front. The opposition to PM Nikol Pashinyan has concentrated its remaining energies to oust him by staging continuous demonstrations in central Yerevan. Here too many unknowns complicate to predict how the internal situation will impact the negotiations with Azerbaijan. Yet, the indications at hand show that the opposition is unlikely to succeed. Similar to neighbouring Georgia, the opposition in Armenia, in many ways, is not sufficiently attractive for the wider masses.

Pashinyan is also likely to survive because of the growing discrepancy in expectations and motivations between the public in Armenia and the powerful Armenian diaspora abroad. Increasingly, the public in Armenia is favouring some progress around Nagorno-Karabakh.

Yet another unknown in the unfolding geopolitical revolution in the South Caucasus is the emerging rapprochement between Armenia and Turkey. In many ways, the potential peace deal with Azerbaijan will depend on how Yerevan handles its ties with Ankara. Earlier examples show that achieving reconciliation with Turkey cannot be independent from the changes in relations with Azerbaijan.

The push for improvement of ties follows earlier positive steps when Yerevan allowed Turkey and Azerbaijan to use Armenian aispace. The Armenian government also introduced a five-year government action plan with the normalisation of relations with Ankara as one of the priorities.

Thus, Armenia is revolutionising its foreign policy and the timing is propitious for bold moves. The opposition inside the country is weakened, while the momentum to sign an overarching peace agreement with Azerbaijan and reach a rapprochement with Turkey is growing.

There are also immense economic benefits for Armenia to be reaped from the opening. The embargo on Turkish goods was lifted. Exports to Turkey would help Armenia improve its fragile economic record and open up new areas for cooperation. Indirect Armenia-Turkey trade remained stalled for years and was just a meagre $3.8 million in 2021. Moreover, Turkey could also act as a potential transit for trade with the EU. Armenian goods could reach the European market, while trade with Turkey could turn Armenia into a transit country. A peace deal with Azerbaijan potentially would guarantee the revival of the stalled railway project to Russia.

What remains to be seen is Russia’s position. As Armenia’s security guarantor, much hinges upon Moscow’s willingness to facilitate the improvement of ties between Armenia and Azerbaijan and Armenia and Turkey. It is still unclear how Russia benefits from Armenia’s moves. After all, Moscow’s ability to tightly control Armenia’s foreign policy has been based on the latter’s geopolitical isolation. Therefore, Armenia’s opening would be changing many facets of this arrangement. Russia’s position will no longer be the same.

But viewing this diplomatic process as if orchestrated by Moscow might not be a correct way to explain the developments. Russia might be resigned to accept changes in the South Caucasus. This is no longer an era of exclusive control over the region and the Kremlin is well aware it cannot exert enough influence to singlehandedly dominate Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia. Moscow might simply be unable to prevent the emergence of other major actors from penetrating the region. And Turkey is one of such players. Therefore, it is not necessarily about definitive decline of Russia’s influence (though some string arguments could be made to support this idea too). Rather we are dealing with a more or less even distribution of power in the South Caucasus.

Emil Avdaliani is a professor at European University and the Director of Middle East Studies at Georgian think-tank, Geocase.

See Also

EU and US Unlikely to Provide Meaningful Assistance to Armenia

Russia and the Eastern Partnership: Protracted Confrontation

Armenia's Pursuit of Western Allies in the Wake of the Failed Russian Alliance

Building a New Beginning: Struggles and Triumphs of Armenians from Nagorno-Karabakh