Trade Networks in the South Caucasus: Future Plans and State of Art

The post-2020 years were crucial to discuss how the new trade and communication routes crossing the South Caucasus should be defined and drafted. The situation on the ground changed significantly in 2023, and the provisions of the 2020 tripartite statement no longer suit all its parties. While the signing of a peace agreement keeps being procrastinated, different actors are already moving on with legs of infrastructural projects.

The 2020 Project

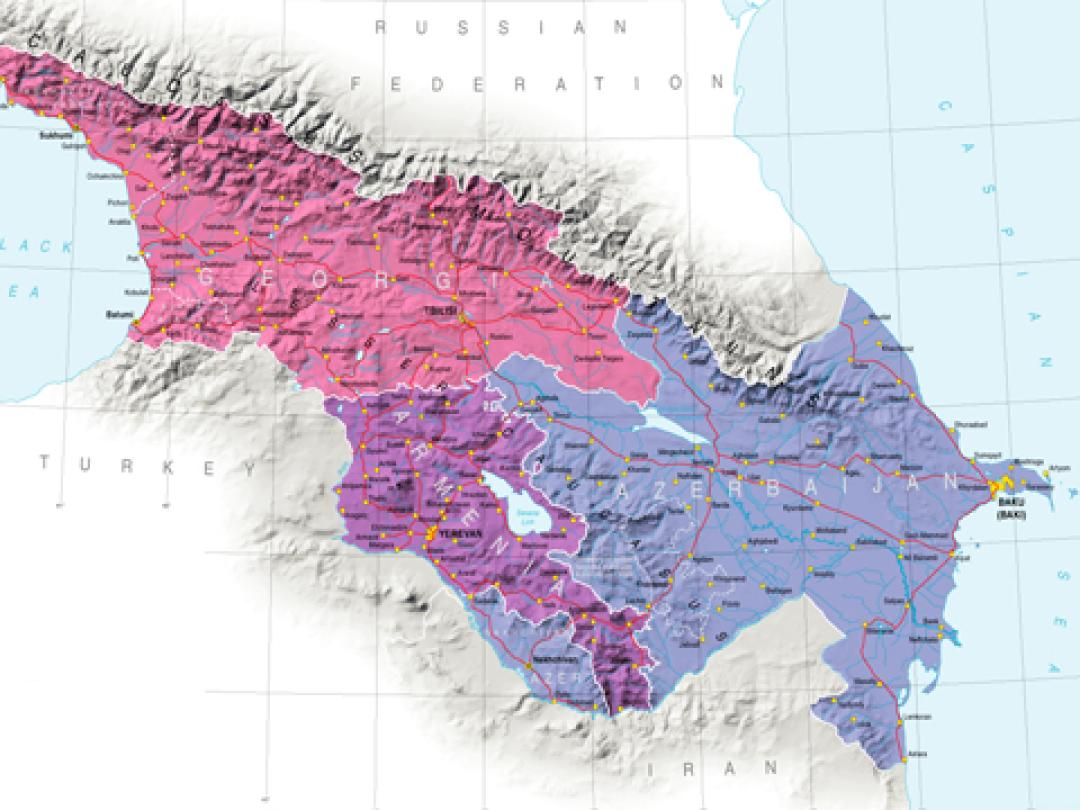

Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, the South Caucasus has not been a region but three states that at most could agree bilaterally because a rift divided the region in two with a wall made of trenches. The Nagorno-Karabakh conflict has always divided the region, not only because Nagorno-Karabakh was a territory with unrecognized statehood and, therefore, untreatable as a trade partner, but also because the closures of the Armenian-Turkish and Armenian-Azerbaijani borders have made the region impassable in its more short and cost-effective communication routes.

The end of the Karabakh conflict, in conjuncture with the war in Ukraine and a particularly positive phase in Azerbaijani-Turkish relations, has opened a new perspective that has attracted international attention. Finally, the South Caucasus could be unlocked, and both east-west and north-south transport ways that cross the region could be significantly encouraged, with the prospect of making it a global hub.

In 2020, at the time of the signing of the trilateral Armenian-Russian-Azerbaijani statement, it was understood that there would be two development directions: a road and rail route from Derbent to Baku, a major north-south artery, would then turn via Shirvan-Sabirabad, Goradis along the Iranian border to Nakhchivan, reopening the direct route from Baku to its exclave without passing through Iranian territory. Here, this main road would split, becoming a new north-south channel to Yerevan, thus giving Armenia access to Russia, an alternative route to the one in use via Georgia. The other main road would have headed west, to Iğdır in Türkiye, opening a direct route between Armenia and Türkiye that Azerbaijan, could also benefit from.

To define the new communication routes the Russian text of the trilateral statement used the words "экономические и транспортные связи" (economic and transport ties) and "транспортныe сообщения," or "коммуникации" (transport relations and communications). However, Baku and Ankara started to refer to these routes as the Zangezur Corridor. This was unacceptable to Armenia because the term “corridor” in the context of the Armenian-Azerbaijani situation on the ground in the years 2020-2023 had a very specific connotation. The only existing corridor was the Lachin Corridor, which enjoyed a special status with goods and people transiting under a quasi-territorial contiguity regime.

The 2023 Factor

Since the exodus en masse of the Armenian community from Karabakh after the September 2023 military operation things have changed significantly. There is no longer any corridor with special status. It is no longer conceivable to envision symmetry between an “Armenian corridor” between Armenia and its demographic exclave in Karabakh and an Azerbaijani corridor between Azerbaijan and its territorial exclave of Nakhchivan. What is left of the trilateral statement, which no longer suits the current situation but yet no one declares obsolete?

For Russia, everything has already been addressed with the trilateral statements, that only needs to be implemented. For Moscow, there is no reason why its border guards or customs officers should not remain responsible for the transits of the new communication routes. Furthermore, not only does Russia already perform this function in Armenia, but it has also increased the need to patrol borders outside Russia. Since 2022, the situation in Russia has also changed, being now under sanctions and interested in having its personnel capable of monitoring the flow of goods that can then be introduced into the Russian market, as in this case through the north-south route.

Armenia sticks to the doctrine that it is impossible to speak of corridors, if this word implies extra-territoriality. Additionally, Yerevan is reversing its stance on the role of Russian border guards, disappointed by the fact that the peacekeepers did not ensure unimpeded transit through Lachin, and they were unwilling or unable to guarantee the persistence of an Armenian community in Karabakh.

Conversely, Azerbaijan, backed by Türkiye, aspires to a toll-free passage, as it understood the “unimpeded communication” to Nakhchivan under the provisions of the trilateral statement. Baku does not intend to subject its goods in transit to Armenian control and fees, for this reason, it is also working on an alternative route through Iran, a traditional option to reach Nakhchivan. This last step has partly recreated the pre-war situation, with east-west and north-south infrastructure in the Caucasus developing around Armenia, without passing through it. Yerevan picked up this card and turned it into an objection to the Zangezur corridor, as Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan emphasised that the 47 km crossing Armenia should follow the same rules that apply to the 49 km crossing Iran, with no extra-territoriality, proving that the selective reading of the trilateral statement is in full swing.

The 2020 statement’s provisions might not necessarily be perceived as binding, in view of the changed situation and of the fact that many of them remained just on paper, e.g. the ceasefire, which was violated, the involvement of the United Nation High Commissioner for refugees for the return of all displaced persons and refugees, and the full exchange of prisoners of war, hostages and other detained persons, a thorny and still unsolved issue.

The State of Art

As a peace agreements is still looming, it is clear that both the parties and partners, as well as the bulldozers, are in action.

Since mid-November, Mangara, the border crossing point between Armenia and Türkiye, is operational again, ready to be opened. The issue of customs with Georgia is also undergoing significant changes. On January 26, Pashinyan flew to Tbilisi for the 13th meeting of the Intergovernmental Commission on Economic Cooperation and the signing of the Declaration of Strategic Economic Partnership. This declaration was accompanied with a discussion on the feasibility of both countries’ customs introducing a model of unified control at border checkpoints, which would significantly reduce the time required for customs procedures.

On the Azeri-Iranian borders works are very active too. The new year kicked off after the inauguration on December 30, 2023, of a new road bridge over the Astarachay River and a new border checkpoint in the cities of Astara on both sides of the border. The projects related to Astara, which required investment and infrastructure rejuvenation, have been discussed, proposed, and studied since the early 2000s, and now the new border bridge has a width of 32 meters and a length of 89 meters. It completes a significant section of an international highway connecting the Iranian city of Rasht to Baku. The new bridge is the fifth border crossing between the two countries and will significantly reduce traffic congestion at the border. It will allow the daily passage of up to 300 trucks. The old bridge could only allow the passage of 200 vehicles per day. Road and rail transport between the two countries have increased by 40% and 47%, respectively. In the second half of January Azəravtoyol, the State Agency of Azerbaijan Automobile Roads, reported ongoing construction work for the road connecting Azerbaijan and Nakhchivan through Iran and the construction of a bridge over the Araz River (http://www.aayda.gov.az/az/news/5788/xvfv-vzxdfvb). The road bridge will be 374 meters long and 27.6 meters wide, consisting of 4 lanes, 2 safety lanes, with 2.8-meter-wide sidewalks in both directions.

Negotiations with the Russians and Azerbaijanis on the construction of the Rasht-Astara railway, another long-discussed project, have also had a positive conclusion. Russia will provide a loan of 1.3 billion euros to continue the construction of the railway, which is expected to be operational in 2027. The railway will unite the railway systems of Iran, Azerbaijan, and Russia. In January, Russia Deputy Prime Minister Alexey Overchuk visited to Baku to sign a roadmap for economic and trade cooperation for the years 2024-2026. On this occasion, it was noted that the volume of trade between the two countries has more than doubled since 2017, exceeding $4.3 billion last year, and the total volume of freight transport has increased by 87% compared to 2017, including the volume of transit goods, which has nearly quadrupled. In addition, the volume of freight transport along the north-south international transport corridor has increased by 44% compared to 2017.

Diplomatic missions and meetings also speak load about the ramifications of the planned, projected, or already under construction infrastructures and their potentials on a wider region than the Caucasian strip of land. There is renewed interest among the Balkan states, which would be the gateway to Europe from the Caucasus, with the thaw in Armenia-Bulgaria relations and the early-year meetings between Armenia-Croatia and Armenia-Greece. Azerbaijan is active with Bulgaria and beyond, including Germany, a relationship that seems to have irked the Kremlin. But the spectrum expands broadly. New synergies are noted between Armenia and Kazakhstan and also between the United Arab Emirates and Azerbaijan, just to wrap up the early-year diplomatic meetings.

Contributed by Dr. Marilisa Lorusso

See Also

NATO and the South Caucasus: Lack of Vision or Strategic Withdrawal?

Georgia in 2026: Between Great-Power Fault Lines and Internal Fractures

U.S.–Armenian Relations Amid Shifting Power Dynamics: Expectations and Challenges

Ukraine War’s Spillover in the North Caucasus