A New Era in Eurasian Connectivity

The eurasian continent is experiencing a wave of new connectivity patterns. The much-touted Middle Corridor is one of them. Another is the North-South corridor, which has been dormant for decades but is seeing new hope following the shocks caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Russia, India, and Iran came up with the concept of the International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC) in the early 2000s as they were actively looking for ways to diversify their economic relations with the outside world. With the signing of the intergovernmental agreement, a concept for a 7, 200 km-long multimodal transport corridor from India/Iran to Russia was created. The idea, however, has seen little meaningful progress because of the Western sanctions imposed on the Islamic Republic. Russia was hesitant to invest money, and its relations with the West were not as bad as they were after 2022. Iran was important, but not as much as close economic ties with the EU.

The situation, however, drastically changed with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022. For instance, Russian President Vladimir Putin’s visit to Iran in July 2022 highlighted Moscow’s new preferences with regard to Iran in striking contrast to the pre-2022 period. A month later, the heads of the customs authorities of Azerbaijan, Iran, and Russia signed a memorandum on the facilitation of transit traffic.

Moreover, in May, Russia and Iran signed an agreement on financing the Rasht-Astara railway link, which has remained incomplete and slowed the implementation of the corridor. The money will come from Russia, which once again shows the scope of the urge Moscow has been facing to find a proper alternative route. The 170-km-long railway link is due to be completed by 2027, and will mainly be financed by Russia, and will evolve into a continuous transport link from Iran’s southern seaports to Russia’s Baltic Sea and Black Sea ports.

The expansion of the INSTC fits into the overall development of Russian-Iranian relations following the war in Ukraine. The two countries saw massive growth in trade and military ties. Indeed, by the end of 2022, mutual trade between Russia and Iran had reached record levels of $4.9 billion, exceeding the figures for 2021 by more than 20%. The boost to bilateral trade takes place mostly through the INSTC.

There is another development, too. Since 2019, an interim agreement on a free trade zone has been in force between Iran and the Russia-led Eurasian Economic Union (EEU). It was supposed to expire in October last year, but the agreement was extended by a special protocol until 2025.

The benefits of the INSTCs are obvious. Firstly, it means faster delivery of goods from India to Europe. In fact, the INSTC can link Russian ports with those in the Persian Gulf and India, a goal that sparked the Russian imagination during its imperial expansion in the 19th century. Russia and India both benefit from easy access to warm-water ports, which offer an alternative to time-consuming sea routes for commerce to Turkey, Russia, and the rest of Europe. The ideal path from the Baltic Sea to India through Azerbaijan and Iran would take 18 days. Deliveries of products via the INSTC may be made twice as quickly as those made via the Suez Canal marine route.

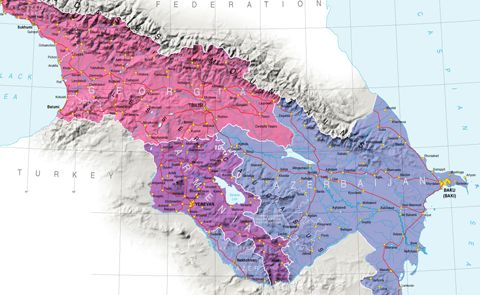

The INSTC consists of three major transport branches: to the west of the Caspian, across the Caspian, and to the east of the Caspian. The intensity of trade going through these three corridors varies. But the most active branch seems to be the western one, which goes through and connects densely populated areas of Russia and Iran. Moreover, the route is also a much shorter land variant than the one through Central Asia.

There are competing projects too. While the Middle Corridor does not directly hinder the operation of the INSTC, Iran, and Russia might be less interested in throwing their full support behind the initiative, which circumvents their territories. There are also alternative north-south corridors, though their fate is far from certain because of the lack of financial incentives. For instance, in early March 2023, Armenia proposed a Persian Gulf-Black Sea corridor to connect India with Russia and Europe. Interestingly, the offer came at a time when Armenia's foreign minister, Ararat Mirzoyan, was also visiting India.

There are also purely geopolitical challenges. Tensions are also persistent in Azerbaijan-Russia and Azerbaijan-Iran relations. Amid the war in Ukraine and Azerbaijan’s increasingly assertive position toward Armenia, Baku’s push to have Russian peacekeeping forces withdrawn from Nagorno-Karabakh by 2025 becomes ever more evident. Russians are understandably apprehensive, but their influence over Azerbaijan's behaviour is limited. Moscow needs Azerbaijan as a transit state and will be far more tolerant toward Baku.

There is also a fear of a potential escalation between Azerbaijan and Iran. The two share uneasy relations because of interlocking ethnic, military, and overall geopolitical tensions. Baku and Tehran will strive to remain pragmatic when it comes to mutually beneficial economic ties, but a lack of trust could complicate the regional situation.

Overall, though its completion is far from guaranteed, the changing pan-Eurasian geopolitical scene favors the expansion of the INSTC, turning it into a massive connectivity pattern connecting Russia with the Global South.

Emil Avdaliani is a professor of international relations at European University in Tbilisi, Georgia, and a scholar of silk roads.

See Also

From Neorealism to Neoliberalism: Armenia’s Strategic Pivot in Foreign Policy After the Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict

Georgia and Russia: New Turn in Bilateral Relations

3+3 Initiative as a New Order in the South Caucasus

Economic Cooperation Between Armenia and Georgia: Potential and Challenges Ahead