Gulshan Sachdeva: What's 'Strategic' About New Delhi's Partnership with Yerevan?

India is becoming ever more engaged in the South Caucasus. After the Second Karabakh War in 2020, Armenia was seeking strategic partners to address some of the apparent strategic imbalances. Armenia turned to India.

The visit of India’s foreign minister Jaishankar in October 2021 was the first of its kind for independent Armenia, paving the way for an ever-deepening bilateral partnership with economic and national security dimensions. As India’s economic and military power is on the ascent, this partnership is becoming increasingly significant for Armenia.

The national security dimension of this partnership usually entails the narration of a “shopping list.” India has concluded agreements with Armenia for the supply of multi-barrel rocket launchers, SWATHI weapon-locating radars, counter-drone systems, drones, anti-tank missiles, and artillery guns. Strategically, New Delhi sees Yerevan as a launchpad into an emerging procurement market that is likely to expand as the Russian defence industry focuses on the war in Ukraine.

However, as Russia reorients its economy from the Atlantic to the Indian Ocean and the Pacific, Armenia sees in India a potential economic partner. Both economies have been making gains from the war in Ukraine. Armenia is engaged in Russia’s digital economy and is a hub for transit of industrial and technological goods. India has gained privileged access to energy and industrial inputs that could supercharge its potential. In September 2022 India and Armenia signed a memorandum that envisaged cultural, digital, and energy cooperation.

From Russia, India has secured preferential access to oil, gas, fertilizers and has gain a competitive foothold in a market that previously looked to the West. This economic pattern sets the stage for the long-forgotten International North-South Trade Corridor (INSTC), of which Armenia is a part, creating new trade routes from the Baltic Sea to the Indian Ocean. India aims to extend INSTC to Armenia, connecting Chahbahar port in Southeast Iran to European and Eurasian markets. This plan also envisages closer cooperation with Iran and the three countries have been organising regular trilateral forums.

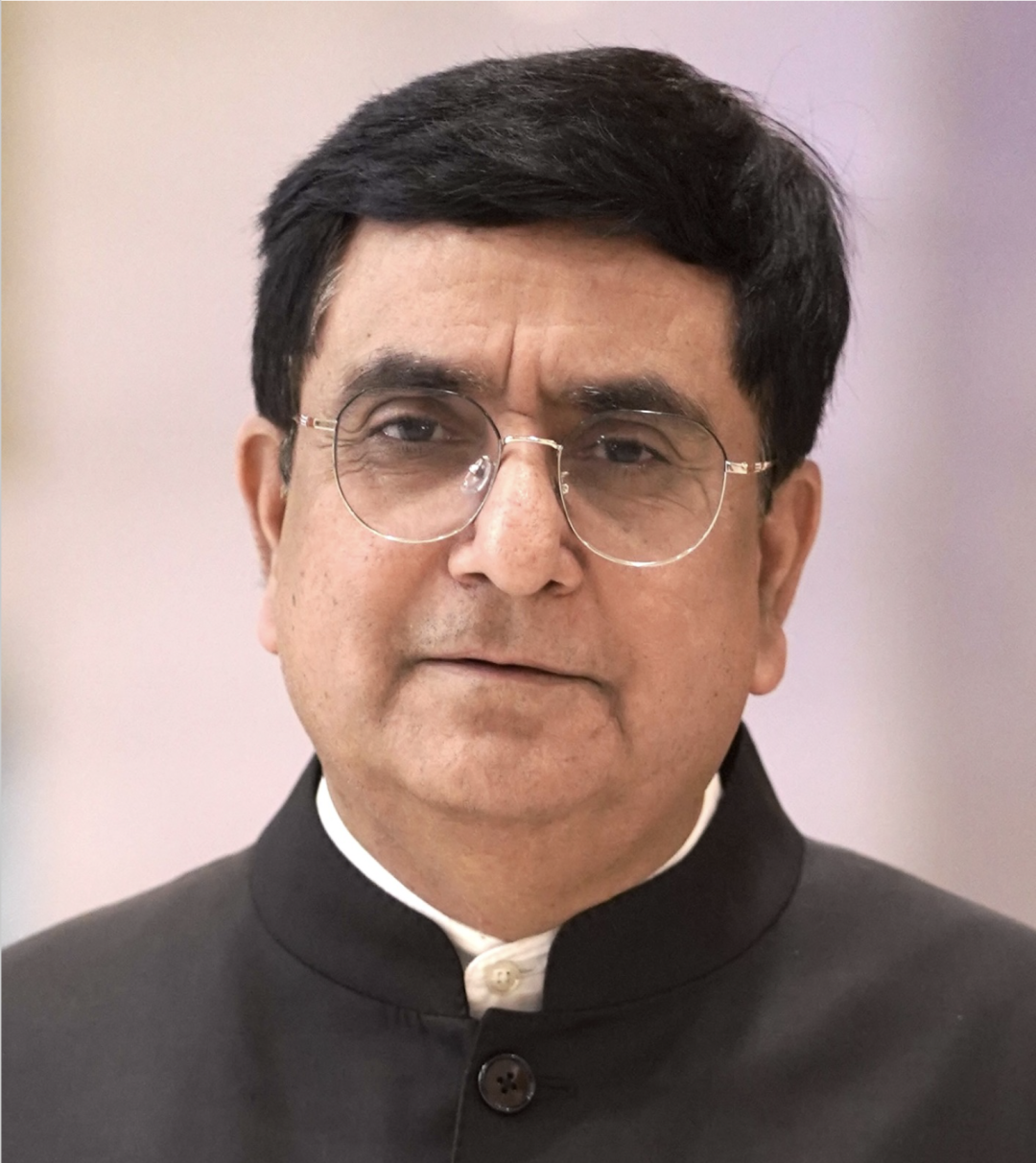

To gain a better understanding of this relationship, Caucasus Watch reaches out to Professor Gulshan Sachdeva, the Jean Monnet Chair and Coordinator of the Jean Monnet Centre of Excellence at the School of International Studies at Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU), New Delhi. He is one of India’s foremost experts on the EU and Eurasian integration with deep knowledge of India’s engagement with each and every state in the region.

Because of the war in Ukraine, there is renewed attention on the International North-South Corridor linking Russia to India via Iran. The “Pivot to the Pacific” has received new attention as Russia disengages from Europe. The discussion is perhaps even more pertinent now, as shipping companies divert trade from the Suez. However, given that this is a plan that has been there for over 20 years, from an Indian perspective, I wanted to ask you: is this an oversold project?

The INSTC has been discussed for 20 years now and is referenced on every discussion on Indian connectivity, whether we talk of trade ties to Europe or Central Asia. There have been ups and downs, more or less confidence in this specific vision and whether it can work. I think a key issue that holds this vision behind has historically been the volume of India-Russia trade. Just before the breakup of the USSR, this was India’s number one trading partner. In the 1990s the significance of this trade declined. In 2000 we signed a strategic partnership agreement with Russia and, since then, we were trying to translate good political will into a commercial partnership. That never happened.

The main issue is that there were no trade volumes to support the existence of a corridor. So, no one was confident that this vision was really going to work. Then the discussion on connectivity heated up, particularly following the articulation of the Chinese Belt and Road Initiative, prompting US and European responses. There is a broader plan for an India-Middle East-Europe corridor and there are individual connectivity visions: Turkey, Japan, etc. Competition brought renewed interest in the INSTC. And any discussion on Indian connectivity has included a reference to this vision. Whatever happens, this will play a role.

So, things have changed. New Delhi is working on the Europe-Asia connectivity partnership with the EU, we have started working with Japan on the Asia-Africa corridor, and we have some of our plans within ASEAN and neighbouring countries. Within this discussion, INSTC has been a key talking point whatever happens next.

The boost in energy trading with Russia does focus minds on the INSTC, as trade turnover last year surpassed $50bn, up from just $10bn few years ago. We need to see of course whether this is “an instance” or a trend. India’s proximity to the Middle East historically meant that our main suppliers were from that region. That is now changing as Europe is sanctioning Russia and Moscow is looking for new markets, including Malaysia, China, and India. The discount rate will play a role.

I think we are looking at a trend and that means the leadership in Moscow and New Delhi will be looking for ways to address the trade imbalance and diversify the kinds of things Russia buys from the Indian market. Russia has been accumulating rupees that have to be spent in India, at least in part. Of course, India also pays in dirham (UAE) and renminbi (China). The state of play in bilateral trade is still in flux, but chances are that the volume of trade will diversify. That fuels the prospects of the INSTC for the years to come.

Historically, the INSTC has seen bottlenecks in Iran, whose internal railway network for instance leaves a lot to be desired. What is keeping India from materialising investment within Iran, particularly around the Chabahar port that individual analysts see as a potential gateway to the Eurasian Customs Union? Do you have a picture of what holding Indian investment back?

Well, as I mentioned, the first issue has always been insufficient trade volumes. When India started out investing in the Chabahar Port, US sanctions were of course rein-introduced. Consequently, Indian companies with exposure in the West were reluctant to be exposed to the Iranian market. That calls for greater state involvement, of course. Clearly, the investment to date in Iran is not as significant as earlier expected.

There are difficulties of working in Iran. The shipping sector does not like “multimodal” arrangements, such as offloading ships in Bandar Abbas to railways, taking on extra cost and time. In my discussion with companies, it is clear that companies will manage any sort of logistical difficulties if there is a viable market. That requires volume: any trade route must compete with others. This is not just a matter of geopolitics. The economics has to work. Now, it increasingly makes sense to invest. Indian state-owned companies can open the way and that is now a distinct possibility.

Indian companies know that both their Iranian and Russian partners are under sanctions. This entails risk. These sanctions will remain in place for at least two-three years. But, if the volume is there, even this obstacle can be overcome. Governments and companies can work through difficulties.

You mentioned using currencies alternative to the dollar like the Emirati dirham. The Emirates and Iran are the new entrants into the Eurasian Economic Union. Is India next in line?

During the visit by the Foreign Minister of India, Jaishankar, to Russia, there was a formal acknowledgement of India’s intention to create free trade linkages with the Eurasian Economic Union. This was announced. The Russian Ambassador said last week that India is opening up negotiations for a trade agreement with the Eurasian Economic Union.

There is a broader pattern here. The recent enlargement of BRICS also includes most of the Middle East players we have been discussing, such as Iran, the UAE and Saudi Arabia. All of them are alarmed by the weaponization of the financial system by the West and are reflecting on parallel mechanisms, beyond the scope of western regulatory outreach.

Certain interests are converging. The UAE President Mohammed bin Zayed Al Nahyan has just finished his India visit and Indian Foreign Minister is now on an official visit to Tehran. India has also signed an FTA with the UAE recently. Indian conglomerates have invested in Israel and plan to invest in Greece. There is clearly going to be a bigger space for cooperation between India and the Eurasian space over the next few years.

Another dimension of the Russian-Indian relationship that is changing is that Russia needs all its arms. There have been delayed deliveries for systems needed in Ukraine, such as the S-400 missile systems, or indeed anything that is not produced under license in India. Subsequently, there has been diversification of defence procurement in India to decrease dependence on Russian platforms. By the same token, some see an opportunity as Russia’s global share in the defence procurement market shrinks, as India could step in to fill the vacuum. Armenia, if I am not mistaken is a prime example of these exports. Do you feel that this agreement with Armenia is indeed significant or is it overstated? And is the deal with India essentially a deal with Russia?

The ambition in India is to diversify procurement to avoid the dangers of singular dependence, which are well known. This is a trend that started years ago, with India making procurement deals with France, the United States, Israel, and other sources. At the same time, the Indian economy is growing, and we continue to face major security threats, not least from China. So, chances are that India will continue to be a major defence procurement market. Russia’s role within this mix is likely to come down from a 60-70% today to a smaller share, but Moscow will continue being an important partner.

Of course, one worries that the war in Ukraine causes disruptions in supply. Despite reports to the contrary, the fact is that the Russian defence industry has been able to restore the flow of deliveries with only few delays. They have ramped up the production.

There is also ambition in India to develop an export industry. There are certain reports on what India has exported in 2022 and 2023, but one should note that significant exports to Armenia have been ongoing since 2017, long before the war in Ukraine. The scale now is of course more significant and there is a wider range and more volume. India clearly needs to become an exporter. Many of the systems sold are indeed produced under Russian license, but there are also systems co-produced or exclusively Indian owned. Some of the products started out 20-30 years ago as “under license” and have since evolved incrementally into Indian platforms. So, not everything needs Russian clearance to be exported and I have not been informed of any substantial bottlenecks in the materialisation of these contracts.

Often there is a need for political or technical consultation with Russia for the export of specific systems, particularly in a market like Armenia, where Russia has held a prominent position. However, legally, India can sell globally a range of systems without license. This is an ambition that goes beyond the specific geopolitics of the Caucasus and Central Asia. India has been selling to Vietnam and some countries in Africa, but Armenia is a good pilot for the internationalisation of indigenously produced platforms. India is testing the waters in Armenia, for platforms produced and tested by our armed forces for more than a decade.

Beyond buying from India, Armenia wants to pursue a similar strategy of diversification away from singular dependence on Russian platforms. And in that respect our cooperation goes beyond defence procurement and extends into training and systems’ inter-operability. India is an expert in evolving Russian platforms and integrating platforms of varied providence, a know-how very much needed by Armenia.

Beyond the “Made in India” drive that underpins New Delhi’s industrial policy – over and beyond military procurement – there seems to be an implicit “the-enemy-of-my-enemy-is-my-friend” logic underpinning defence cooperation. Pakistan and Turkey have a major defence partnership and Baku-Ankara-Islamabad conduct military exercises under the “three brothers” banner. There was apparently some Pakistani assistance to Azerbaijan on a tactical level during the Second Karabakh War, not least because of Islamabad’s experience in the Afghan frontier with mountainous warfare. Is this a rhetorical oversimplification or is there some substance in this perception?

I have seen some of these reports in India. India does have difficult relations with Pakistan. However, India’s relations with Azerbaijan and Turkey are not the same as Armenia’s. Yes, the rhetoric on Kashmir emanating from Baku and Ankara are a problem for India. But New Delhi is not looking to have an adversarial relationship with these two countries.

Whatever happens between India and Armenia, I do not see a serious “camp-like” delimitation. There is an element of messaging here and there, but the main drive is procurement. Armenia has shown willingness to buy your systems, to test their inter-operability with other platforms, and to use this case study to reach out to other potential clients. There are countries using Russian platforms for decades who look now to India as a possible procurement partner, like Syria for example.

The main driver is establishing yourself through Armenia, particularly in anti-drone systems. This is useful both in Armenia and the Middle East.

Armenia is developing in parallel to India as a digital economy hub, with a small country of four million people boasting more than five so called “unicorns” (start-ups valued at over $1bn). Do you see scope for synergy with India’s global power, including the arms procurement industry?

Many post-Soviet states have a similar ambition, like Estonia, with whom India works closely. As you said, Armenia has a talented workforce, competence, and networks. I think there is scope for cooperation across a number of sectors, not least defence and counterintelligence. Once you have a core understanding, there is incremental development of cooperative frameworks.

Is there anything left of the Persian-Armenians who settled in India during the days of British rule?

I am not a historian, but Armenians did settle in Calcutta, Gujarat, Chennai, and other places. You can still see the architecturally distinctive churches in Calcutta, where there are also schools and clubs. However, we are talking about a few hundred people, not more.

Recent developments are in this respect more significant. There are thousands of Indian students across the Caucasus, including Armenia, mostly studying medicine. Indian students, who are not able to get college seats because of huge demand and tough competition and cannot afford the UK or the US, often go to other cheaper European markets. These Indian students are cultural ambassadors, creating a bridge with the region.

Contributed by Ilya Roubanis

See Also

Irina Mamulashvili: Electoral Interference is a Playbook, not a Recipe

Giorgi Gakharia: The EU Should Engage Georgia Despite Its Democratic Backsliding

Peace or Capitulation? Shahverdyan on Armenia-Azerbaijan Agreement and the Nagorno-Karabakh Crisis

Ali Mousavi Khalkhali: Iran Will Avoid Conflict in the Caucasus