Abkhazia's "Russia" Problem

Russia is reinforcing its stronghold in Western South Caucasus. Moscow can rely on loyalists in the Abkhazian government, like the de facto Foreign Minister, to sedate the independent spirits of the local population and on a campaign of massive investments in strategic infrastructure that will secure a back-up military plan on the Black Sea. Since the breakaway from Georgia, Abkhazia's reliance on Russia has grown to such an extent that Moscow can now exert pressure to stifle the local economy and secure concessions on crucial assets such as the Enguri dam.

In April, a new program started airing on the Kremlin’s flagship TV channel, Channel 1, Global Majority. Inal Ardzinba, the young and ambitious Abkhazian Foreign Minister, hosts Global Majority, a political talk show, with Syrian President Bashar al-Assad as his first guest Ardzinba is a career politician with a strong Russian background and ties; and he is one of the key Kremlin-made creatures in Sokhumi. In January 2020, he founded the Future of Abkhazia Party. In 2021, President Bzhania appointed him as Foreign Minister of Abkhazia, surprising many experts due to his young age. Ardzinba emphasized deepening cooperation with Russia as a priority in Abkhazia’s foreign policy. In 2024, he prevented the entry of the European Union’s Special Representative into the region and is a supporter of the law on foreign agents, which is as controversial in Abkhazia as it is unpopular in Georgia. In 2022, Ardzinba also halted the EU and UNDP’s COBERM program in Abkhazia and proposed relocating the Geneva Discussions to a more neutral city, such as Minsk or Istanbul.

The most recent session in April 2024 also addressed the issue of relocating the Geneva Discussions. In 2008, the EU, OSCE, and UN launched this format with the aim of finding a political solution to the war in Georgia, bringing together Russians, Abkhazians, South Ossetians, Georgians, and Americans at the same table. Its relocation is a topic that raised the Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov, and immediately the two Russian protectorates of Abkhazia and South Ossetia aligned themselves.

The Georgian-Russian conflict isn’t the only one Ardzinba had an active role in. As a previous official of the Russian Presidential Administration in Moscow, Ardzinba dealt with issues related to Ukraine, including interactions with the so-called Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics. In May 2015, the Security Service of Ukraine presented evidence implicating Ardzinba in terrorist activities. Subsequently, he was placed on the international wanted list by Ukraine and accused of attempting to destabilize the situation in southern Ukraine in 2015. In 2016, Ukraine initiated criminal proceedings against him for his alleged involvement in the attempted creation of the People’s Republic of Bessarabia in the Odessa region.

Clearly very close to the Russian government, to the extent of being a television voice for it, Ardzinba has set up the work of the foreign ministry he presides over according to an agenda that seems much more Russian than Abkhazian. And not a few critics in the small republic, which boasts independence from Moscow, have wondered whether it is appropriate for the foreign minister to host a political show in another country. However, these are the waters Abkhazia navigates, and this ostentatious independence is increasingly eroding.

The Turn of the Screw: Infrastructure Investments

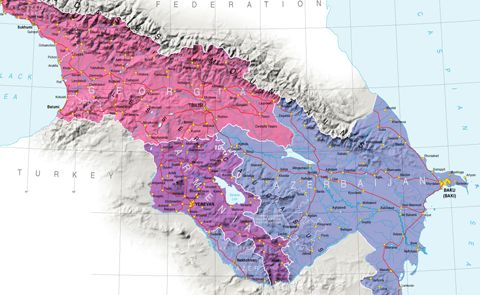

Moscow is putting pressure on its perceived peripheries. Abkhazia plays a special role in meeting Russian needs. With the withdrawal of peacekeepers from Karabakh and the poor relations with Armenia, the Russian military presence in South Ossetia and Abkhazia has increased its significance. The Russian military deployment in Abkhazia is substantial. The 7th Military Base in Bombora, subordinate to the command of the 49th Combined Arms Army and the Southern Military District of the Russian Armed Forces, alone counted approximately 4,500 soldiers before the invasion of Ukraine. Russian officials report that they have deployed two battalions, totaling 800 servicemen, in Ukraine.

Besides the military staff, there are the Russian border guards. Perhaps Moscow has also sought to expand its military Abkhazia presidium, both quantitatively and qualitatively. Rumours circulated in the small republic in 2024, suggesting the deployment of Rosgvardia, the Russian Federation's national guard and internal military force directly reporting to the President, in Abkhazia. The news sparked a scandal and subsequently faced denials. But while this chapter of attempted sovereignty remains frozen, others are steadily melting.

Abkhazia is crucial in the Russian security framework because, with the occupied Crimea and the Russian coastline, it is the southernmost military bulwark available to the federation, and it overlooks the Black Sea, where the Russian fleet is constantly under threat. It is no coincidence that Russia is heavily investing in coastal infrastructure in Abkhazia. The construction of the new military naval base is underway in Ochamchire, close to one of Georgia’s potentially most important maritime infrastructures, the port of Anaklia.

Additionally, Moscow recently took control of another important project: the reconstruction of the Sokhumi airport, which will serve both military and civilian purposes. The once-upon-a-time Sokhumi International Airport has been inactive for three decades, since the Georgian-Abkhazian war. The reconstruction is being carried out through an agreement between Abkhazia and Russia. The Russian Security Council-affiliated Rashid Nurgaliyev's company won the project contract under favorable conditions, causing outrage in Abkhazia.

The revival of the only Abkhazian airport is seen as a means to boost tourism from Russia, especially because it will not be internationally recognized, being the airport of a de facto state, and will limit air travel exclusively to Russia. However, concerns remain about the airport's potential military use, especially in the midst of a war on the Black sea, given that most southern Russian airports have closed due to security concerns. Moreover, the airport's expansion has left some residents dissatisfied with the loss of their homes. Economic compensations for expropriations are inadequate, and villages near this infrastructure question the long-term implications for their community and future generations. These concerns reflect broader anxieties about the purpose of the airport and its impact on local livelihoods and security.

Last but not least, there’s the ongoing saga related to the Bichvinta dacha and the large swath of coastline that Abkhazia was meant to grant exclusively to the FSB. However, it turned out that this was just part of Sokhumi's plan. Moscow has rejected the clause about non-transfer to third parties, so the issue of future ownership and use of the Dacha remains pending.

In the Darkest Hour

Another key area on which Moscow has focused maximum attention-achieving concessions through a series of strangulation manoeuvres - is the energy sector and the control of the Enguri dam. The Abkhaz energy crisis, an everlasting problem since the breakup with Georgia, has worsened due to crypto currency mining activities and has peaked with Russia’s aggression against Ukraine.

In Abkhazia, approximately 40% of the electricity consumed comes from the Enguri hydroelectric plant, shared between Abkhazia and Georgia, with the rest imported from Russia. The lack of gas supply since the early 1990s war has severely strained the energy sector in the breakaway republic. With gas tied to Georgian supply, the secession left Abkhazia, along with western Georgia, without it. Secession hindered restoration, forcing domestic heating to rely on the electrical system.Few people pay for the outdated network, which mismatches tariffs with actual consumption. The system was already in crisis when crypto currency mining, a high-consumption sector, emerged. An opportunity quickly overwhelmed the fragile system.

In the midst of international sanctions, Russia is rabid about crypto currencies, and at the same time, it has cut off economic resources previously supporting the Abkhaz energy sector. Cryptocurrency production in Abkhazia, although profitable, strains its energy resources, allowing Moscow to propose swaps of credit for properties, like controlling the Enguri power plant, further asserting its influence. This plan threatens to cripple Abkhazia’s energy system, which requires significant investments to sustain functionality. Low electricity collection rates, the outdated network, and the energy demands of crypto currency mining have already resulted in rotating blackouts, leading to numerous campaigns to confiscate mining machines.

In 2020, the de facto cabinet adopted three regulations to control crypto-mining, including a two-month ban on importing mining hardware, later extended, and a call for the Ministry of Economy to create a law for a temporary halt to mining. However, mining had become so pervasive that halting it proved impossible. In 2021, the presidential administration held a meeting with local administrators in what became known as a war against mining. It should be noted that the crypto mining market is diversified, with various production capacities, including large centers and smaller, harder-to-identify setups in hotels or private homes, making enforcement challenging.

The energy situation progressively worsened, with further crackdowns on mining in 2021. Repressive measures intensified, with reports of hardware seizures across the country and some facilities consuming tens of megawatts. In January 2021, the de facto president declared an energy emergency as investments from Russia no longer covered modernization needs, urged accurate consumption measurement, fluctuating tariffs, and lamented insufficient paying consumers. Abkhazia began experiencing periodic blackouts due to excessive consumption and network incapacity. Mining was banned nationwide, with continued crackdowns resulting in seizures, including attempts to smuggle hardware across the Georgian border.

With Russia stopping free electricity supply, Abkhazia faces a $2 million shortfall, forcing negotiations for additional funds. Failure to pay risks an electricity cut-off, highlighting Abkhazia’s heavy dependence on Russian support, as evidenced by its mounting debt exceeding 5 billion roubles since 2014.Essentially, Abkhazia sought Russia’s financial aid to cover electricity payments to Russia itself, as it is the main provider for the breakaway republic.

Sokhumi is now exploring what appears to be the only plausible option: leasing three hydroelectric power plants from the Enguri hydroelectric complex to Russia, with an agreement already signed but pending parliamentary approval. The opposition opposes the agreement, warning of its negative effects and potential cancellation after a change of government. The privatization of the power grid could give Moscow control over energy, a crucial asset politically, economically, and socially.

In fear that the president might accept new Russian diktats, whether on electricity or other thorny issues like the sale of property to foreign citizens, which would allow Russians to dominate the Abkhaz real estate market, parliament has adopted a law to limit the president’s ability to sign international agreements. However, as in the case of clauses regarding the transfer of Bichvinta, these manoeuvres risk remaining on Abkhazian paper only.

On the other bank of the Enguri River, the Georgian government’s stance is firm. In November 2023, Davit Narmania, President of the Georgian National Energy and Water Supply Regulatory Commission (GNERC), told journalists that if Abkhazia receives electricity from Russia, they must pay for it, and Tbilisi’s only obligation, stemming from agreements in the 1990s, is the 40-60 ratio of electricity generated by the Enguri hydroelectric power plant, which is upheld. There are no other obligations to Tbilisi. In December, during an Abkhaz-Georgian meeting in Zugdidi, western Georgia, close near the Enguri River, the Abkhaz reportedly requested an increase in the energy available to them from the shared dam production, but to no avail.

Time and numbers are not on Sokhumi’s side. The outcome of the Russian elections in Abkhazia, excluding military polling stations, delivered over 93% approval votes for Vladimir Putin. All these numbers, all increasing, including the oppressive debt and Russian presence, depict a progressive cannibalization of Sokhumi’s independence ambitions.

Contributed by Dr. Marilisa Lorusso